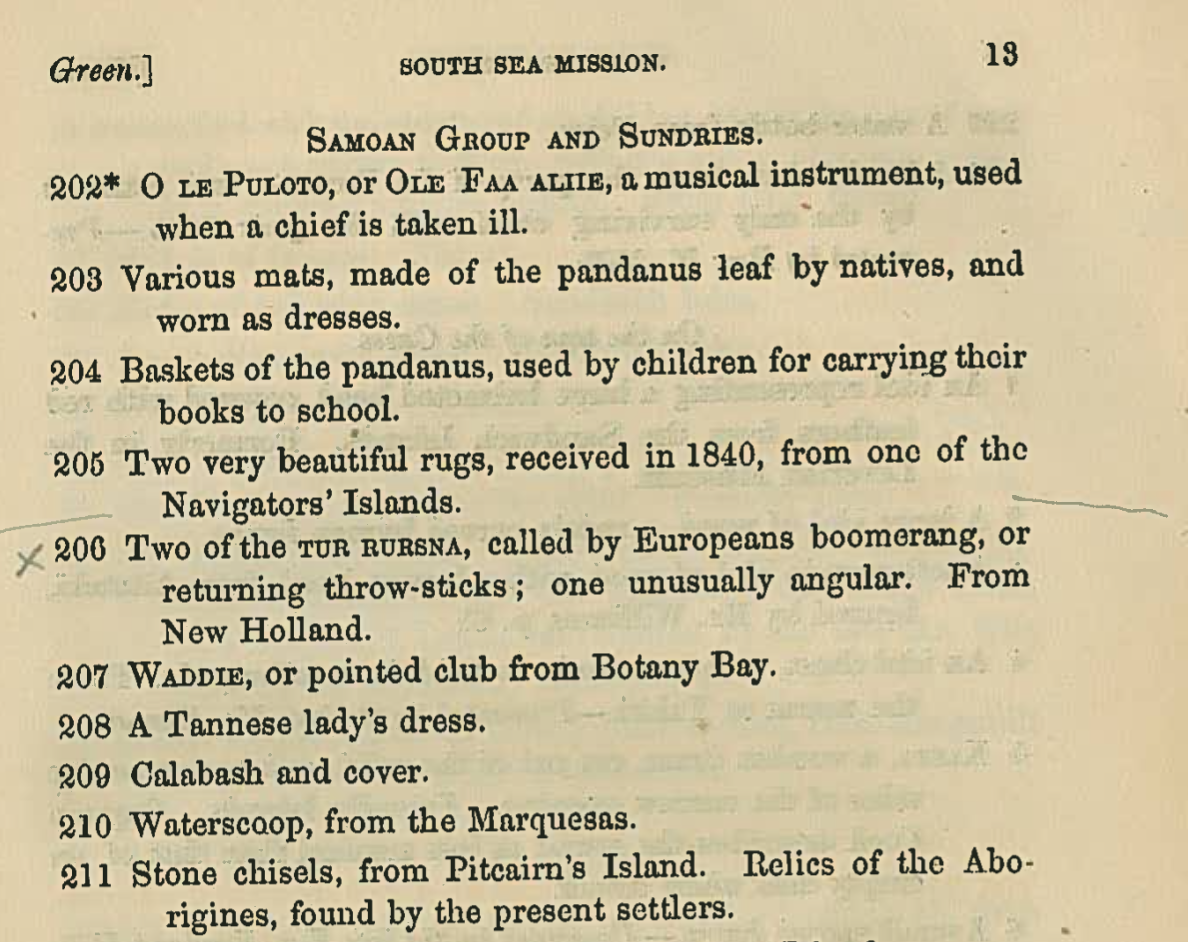

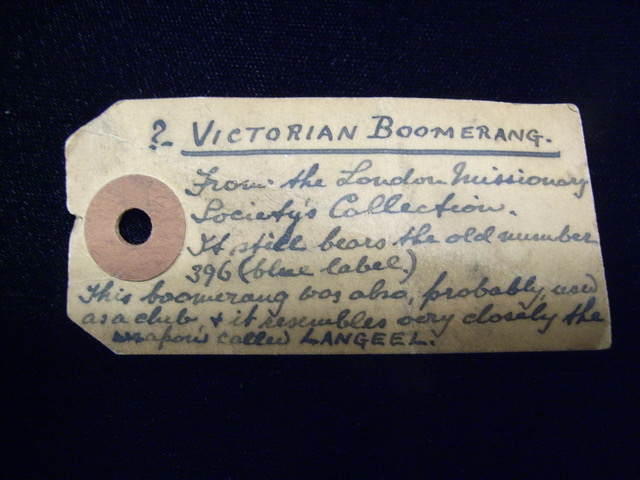

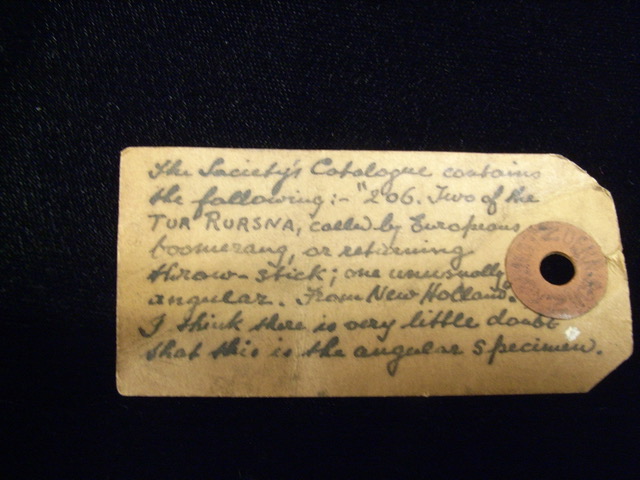

called by Europeans boomerang, or returning throw-stick; one unusually angular

Bahtabah, 21 May 1825

Australian Club acquired in 1958 by the Field Museum, Chicago, as part of Captain A.WW.F. Fuller's collection

© The Field Museum, Image No. 272363_front, Cat. No. 272363, Photographer Ellen Bushell

Field Museum (272363)

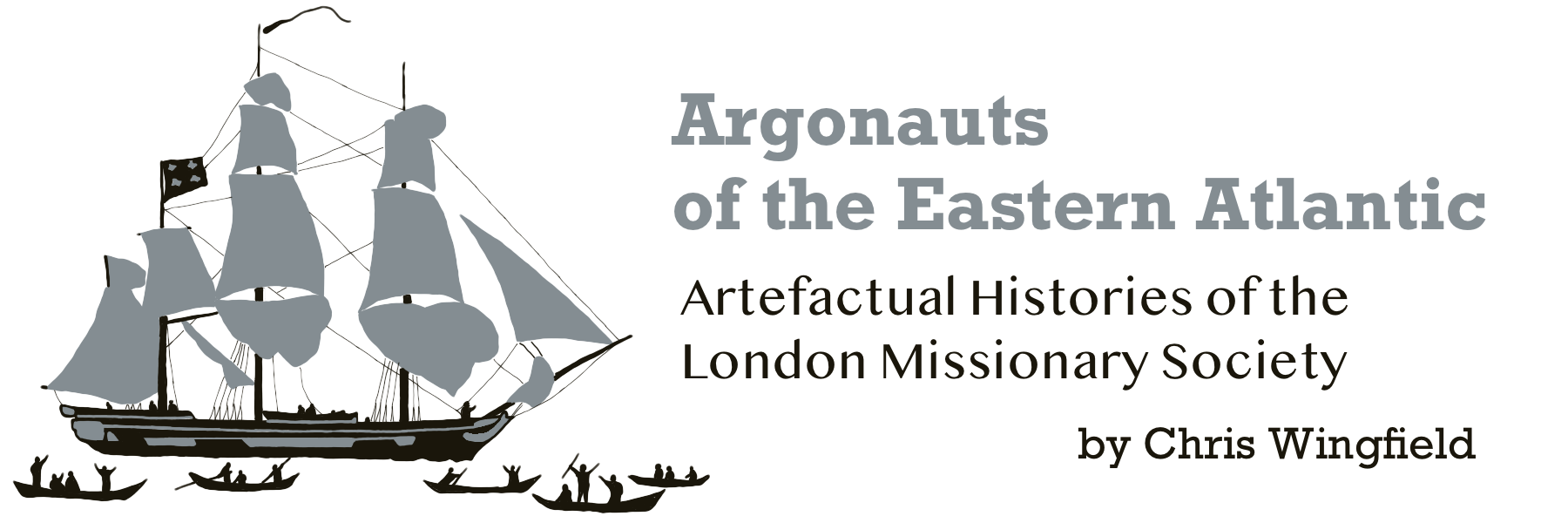

Visiting Chicago’s Field Museum in June 2010 to see items purchased from the London Missionary Society’s museum by Captain A.W.F. Fuller during the mid-twentieth century, I was surprised to encounter a number of Australian artefacts – four spears and a club. Having briefly worked on a project in northern Australia in 2003, I knew missionaries played a significant part in Australian history, but associated this with other missionary societies and other places.

The closest the London Missionary Society missions had got to Australia, or so I thought, were the islands of the Torres Strait, lying between Australia’s northeastern tip and Papua New Guinea. Having been sent a scan of Captain Fuller’s personal copy of the Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, published in the mid-nineteenth century, by the Bishop Museum in Hawai’i, I could see his pencil cross alongside the description for item no. 206, which provides the title for this chapter (he also wrote ‘LM Socy’ in pencil, directly onto the artefact in question – Field Museum accession number 272363 – image above).

While the London Missionary Society’s longer-term history concentrated in Polynesia, Africa, Madagascar, India, China and the West Indies, its first three decades involved engagements in several other parts of the world. Richard Lovett’s (1899) History of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895, published to mark the Society’s first centenary, is structured around these six major ‘mission fields’, but also includes a chapter on ‘Missions Begun and Abandoned During the Century’.1 This includes brief accounts of missions to various parts of what is now Canada between 1799 and 1818, to French prisoners of war in 1801, to a brief mission in Buenos Aires in 1807, as well as to Malta and the Ionian Islands of Greece between 1808 and 1844 and Mauritius between 1814 and 1871.

Listings of missionaries in the appendices of Lovett’s two volumes also include Joseph Frey, a missionary to the Jews in London between 1805 and 1809, and his China section includes an account of the mission to Mongolia between 1818 and 1840. Nowhere, however, does he refer to a mission to the Aboriginal people of Australia. How did such a quintessentially Australian artefact find its way into the collection of the museum of the London Missionary Society, along with a description that at least appears to include the artefact’s name in an indigenous Australian language?

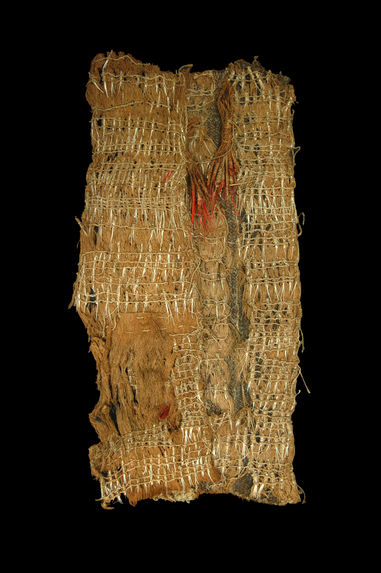

At least part of the answer has to do with Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, the deputation sent by the Directors to tour the Society’s missions in May 1821. Having left them at Raiatea in late 1822, following their return from Hawai’i (Chapter 7), we need to pick up their strand in the story. Spending time with the Raiatean king, Tamatoa III, they learned about Polynesian mythology as well as the historic significance of the ‘maro’, a hereditary robe of royalty covered with red feathers to which an additional section was added on the accession of each monarch.2 Tyerman and Bennet’s account suggests it ‘might be regarded as an hieroglyphic tablet of the annals of Raiatea’, but noted it had been cast off by Tamatoa and sent ‘as another trophy of the gospel victories here to the Museum of the London Missionary Society’ by the resident missionaries John Williams and Lancelot Threlkeld.3 They visited Opoa, centre of the cult of Oro, and former residence of Tamatoa on Raiatea, describing it as the ‘metropolis of idolatry’, which by late 1822 was ‘flourishing in all the unpruned luxuriance of tropical vegetation’.4

Tyerman and Bennet’s described the efforts of the people of Raiatea and surrounding islands to establish a Christian way of life, including through the establishment of law courts that punished even those found guilty of being tattooed, consuming kava or leaving offerings for the deceased, at least initially. At the end of 1822 they witnessed the baptism of 150 people by John Williams and Lancelot Threlkeld, resident missionaries at Raiatea, and in early 1823 they visited the neighbouring island of Taha’a, where they attended the baptism of 198 people, as well as Borabora where they saw 90 more baptised. At Huahine they joined the annual Missionary meeting where a new code of laws was adopted, travelling to Tahiti in mid-May for the annual Missionary meeting, attended by ‘long lines of people… in their various picturesque dresses’.5 The meeting took place in a chapel so large it needed two preachers, where participants donated considerable amounts of coconut oil, arrow-root, cotton and pigs to support further missionary endeavours.

Following the death of Pomare II in December 1821, a regency was established – Pomare’s son and heir apparent celebrated his third birthday when Tyerman and Bennet were at Tahiti in June 1823. They seem to have met with various senior men in their attempts to ensure the new Christian order would not fall victim to this seeming power vacuum. In September, when meeting a chief called Tati, they were presented with parts of the ‘bonnet and two tawdry covering which were cast over’ the idol of Oro, as well as a remnant of the ‘maro’ used to invest Pomare II as king.6 In October, Bennett acquired a fare na atua or god house ‘the only relic of the kind that we have seen in these islands; so utter was the demolition of such things even when the idols themselves were preserved for transportation to England as trophies of the triumph of the gospel’.7 This example had evidently been hidden by priests in a cave in the mountains, and only recently ‘brought to market and sold’.8

At the end of October 1823 they went to Mo’orea for six weeks before travelling to Raivavae in the Austral Islands, where they visited newly constructed chapels and witnessed the baptism of 52 people, following which they were presented with a large quantity of bark cloth.9 Visiting neighbouring Tubuai in early 1824, they saw more people baptised, despite the island suffering an epidemic disease and having only received Tahitian teachers 18 months earlier.10 Returning to Rurutu, where they stopped on their way back from Hawai’i, they attended a church service at which 31 people were baptised. Arriving back at Mo’orea in mid-January and Tahiti in February, Tyerman and Bennet participated in the first Tahitian parliament to include representatives of the common people, convened to consider and adopt a new code of laws. Henry Nott, the Society’s senior missionary, had prepared the laws and presided over the meeting.11

Fare na Atua or 'God House' for Oro figure

Collected by George Bennet at Tahiti in 1823

While one of the forty articles adopted proposed to repeal the law against tattooing, ‘leaving it to persons to act as they pleased in respect to that custom’, a major point of debate arose over the establishment of a suitable punishment for murder.12 According to the summary given in Tyerman and Bennet’s account, while some suggested they should follow English precedent by adopting the death penalty, others pointed out that the death penalty was also applied in Britain for burglary and sheep stealing, which self-evidently went too far. Scriptural authority was cited, but Tati, a chief who ‘seemed a pillar of state’, pointed out that ‘many of the laws of the Old Testament had been thrown down by the Lord Jesus Christ’, and argued that the New Testament should be their guide.13 Pati, the former chief priest of Oro at Mo’orea, who had been the first to burn his to’o (what the missionaries called ‘idols’), pointed out that for Christians, punishment should not be made for revenge but deterrence, suggesting that banishment to a remote island would be more effective in this regard (whether he had the British example of transportation to Australia in mind is unclear). Finally, a commoner argued that another reason for punishment was ‘to make the offender good again if possible’, noting that ‘if we kill a murderer, how can we make him better?’14

With new laws adopted, Tyerman and Bennet, together with the assembled missionaries, presided over the coronation of the infant king on 21 April 1824, the first Christian installation of its kind in Polynesia. The newly adopted code of laws was read to the assembled subjects by Henry Nott and presented to the boy king by George Bennet. Likewise, after he was anointed and crowned by Nott, Daniel Tyerman presented the new King with a Bible, telling him it was ‘the most valuable thing in the world.’ Sailing shortly afterwards to Mo’orea, Tyerman and Bennet prepared to leave for New South Wales in a small (50 ton) schooner, the Endeavour, together with one of the missionaries, Lancelot Threlkeld, who had ‘lately lost his excellent wife’.15 On their way, they stopped at the Cook Islands, where they left Tahitian evangelists to continue the work of conversion, visiting a half-built chapel at Rarotonga (see Chapter 12).

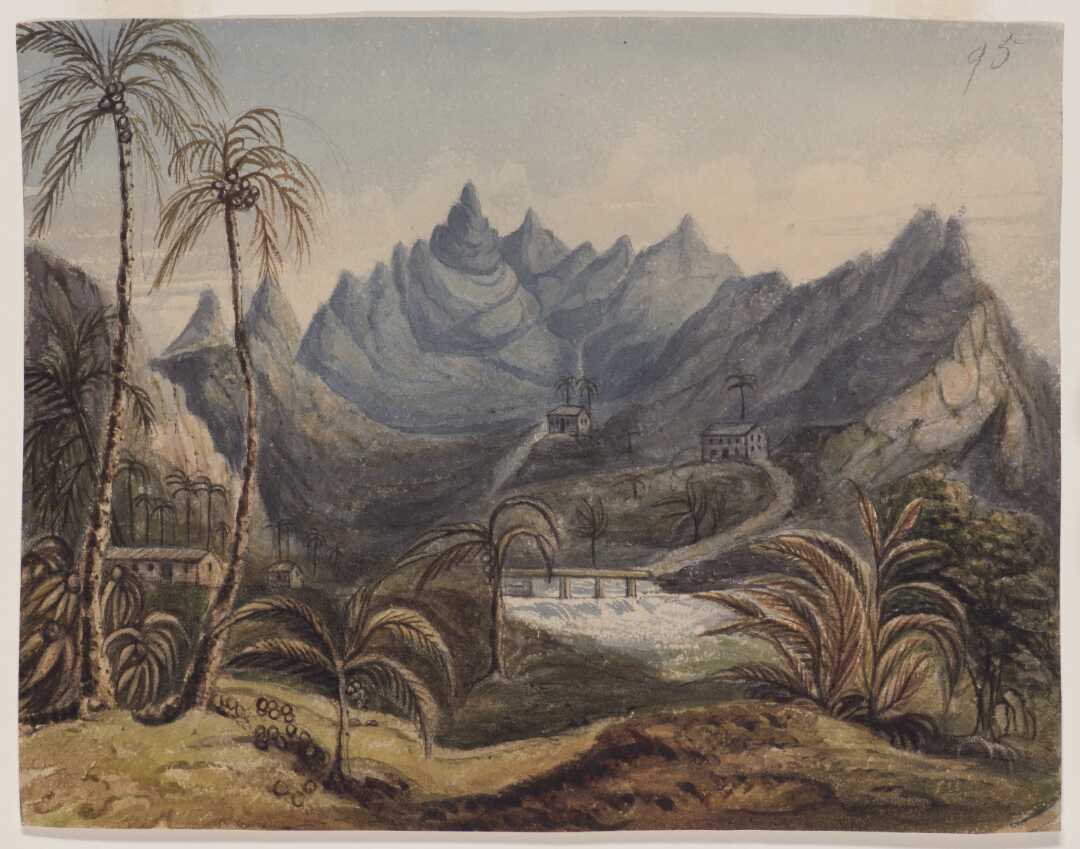

Missionary settlement in the harbour of Papetoai, on the North Side of the Island of Vimeo (Mo'orea)

Cotton Factory on the left; on the right the Houses of two Missionary Artizans, Messrs. Blossom and Armitage. The Trees are the Pandanus, Cocoa-nut, and Banana.

Caption given for Plate 1, Volume 1 in the Journal of the Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq, where this original watercolour by Tyerman was evidently used as the basis of an engraved print, facing p. 95..

Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand A-263-005

After three years spent largely as guests of honour in the newly Christian kingdoms of Polynesia, established around an explicitly missionary religion, the Deputation’s subsequent visits must have been somewhat anticlimactic. On the way to Australia, the Endeavour stopped at Whangaroa Bay in the far North of New Zealand, where a Wesleyan mission had been established a year earlier. The ship’s deck quickly became crowded with Māori visitors, keen to trade, especially for muskets and gunpowder, New Zealand’s ‘musket wars’ in the process of transforming Māori political relationships. It seems likely that some of the 34 Māori artefacts that the British Museum acquired from the London Missionary Society were acquired during trading undertaken at this time.16 In the midst of these exchanges, the ship’s cook suddenly cried out that his cooking pans had been stolen, and someone else that the Captain’s trunk had been broken into.17

When Captain John Dibbs attempted to clear the deck, one of the visiting Māori dignitaries was knocked into the water. The women and children immediately left and the Māori men surrounded those Europeans on deck, including Bennet, Tyerman and Threlkeld, together with Threlkeld’s seven year old son. A man who had until then been trading with Bennet began to shout ’Tangata New Zealandi tangata kakino?’ (Is the New Zealand man a bad man?). Having learned some Tahitian, intelligible by New Zealand Māori, Bennet was able to reply ‘Kaore Kakino, tangata New Zealand, tangata kapai’ (Not bad, the New Zealander is a good man).18 Despite being threatened with a large axe, brought for sharpening by the ship’s carpenter, Bennet attempted to demonstrate peaceful intentions by allowing himself to be cheated into buying the same fish repeatedly, for fish hooks taken in his jacket pocket.

Eventually this tension broke when the ship’s boat returned, carrying William White from the Wesleyan mission at Kaeo, together with Te Ara, Principal Chief of Ngati Ura, who defused the situation. Te Ara had himself served on European ships, and his whipping on the Boyd as a crew member is understood to have led to a revenge attack that saw the entire crew killed in Whangaroa Bay, fifteen years earlier. Leaving Te Ara on board to ensure the ship’s safety, Tyerman and Bennet visited the mission station, hopeful that the transformations they had seen in Tahiti would soon come to New Zealand. This, however, was something to be overseen by the Wesleyans, as well as the Anglican Church Missionary Society (CMS) who had established a mission at the Bay of Islands a decade earlier, under the oversight of the Rev. Samuel Marsden, Anglican Chaplain at New South Wales.

Wooden club (patu rakau), with unfinished decorative carvings

According to an historic label, this was collected by George Bennet in New Zealand during July 1824

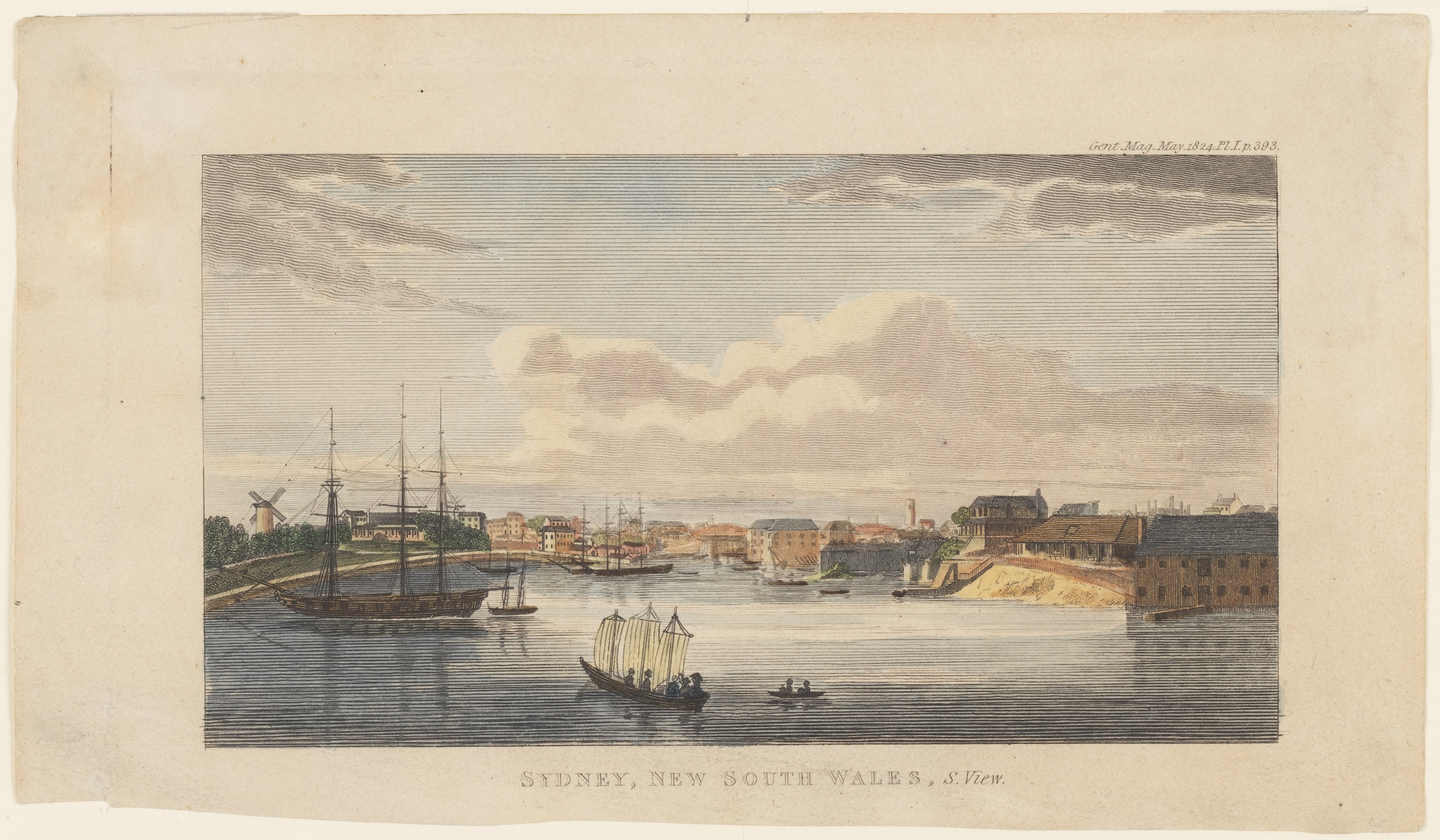

Sydney, New South Wales, S. View, 1824

possibly after a drawing by R. Read, jnr

The Endeavour entered Sydney Cove in New South Wales at midnight on 19 August 1824, a little over 54 years after her namesake, HMS Endeavour, arrived at Botany Bay under Captain James Cook. A penal colony had been established in 1788, after American independence meant convicted criminals could no longer be sent across the Atlantic. Free settlers followed in 1793, and by 1824 European settlement extended up to 100km from the harbour.

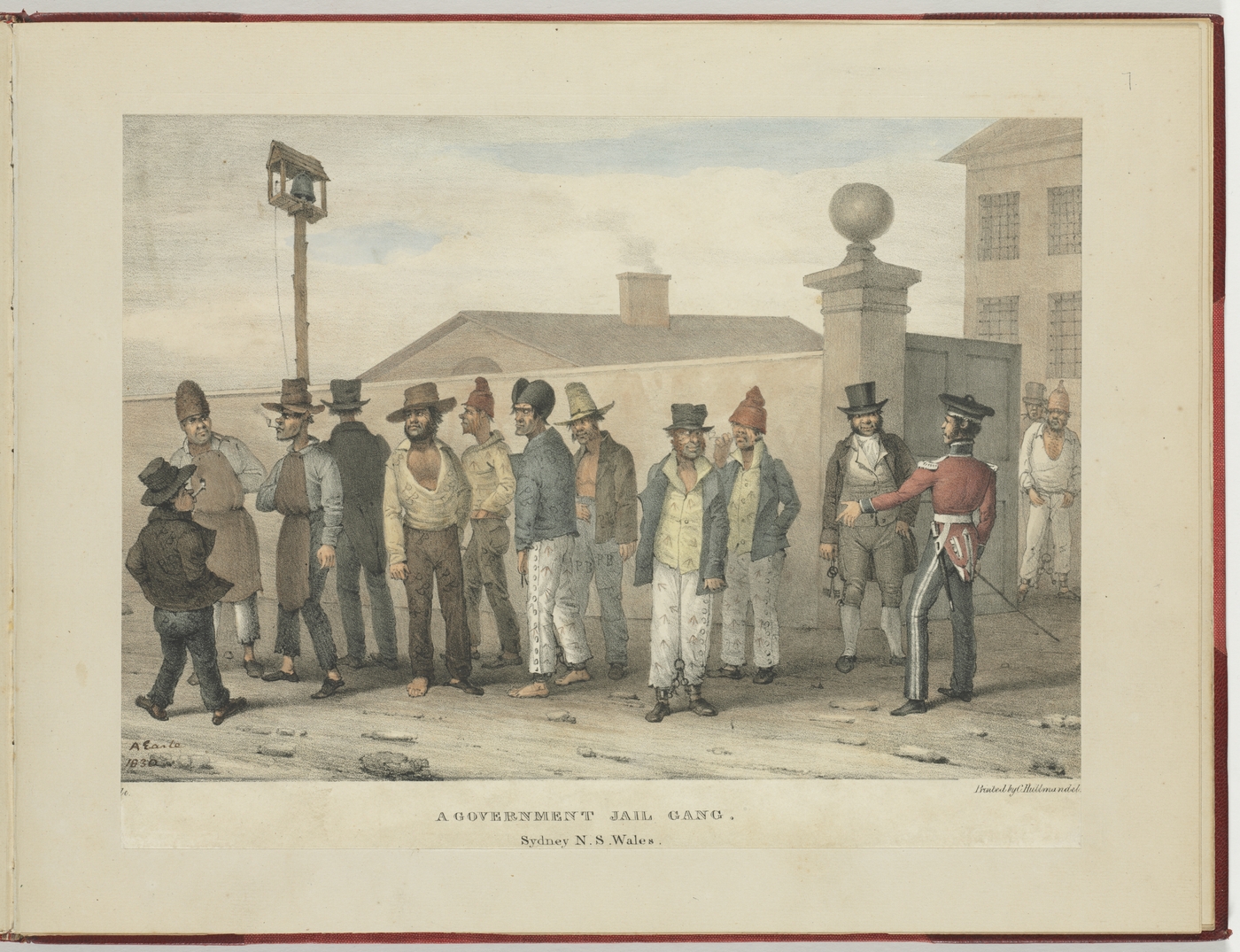

Tyerman and Bennet were immediately struck by the stone and brick buildings of Sydney, as well as its two Anglican churches, two Methodist meeting houses, as well as Scotch and Roman Catholic chapels. They couldn’t help but notice the many convicts, however, ‘going about their occupations in jackets marked with the broad arrow, or some other badge of their servile condition. They are, for the most part, miserable creatures…’.19 Having spent three years with ‘no fear for our persons or our property, by day or night’ they became conscious of the need to ‘look well to ourselves and our locks for security’.20 Threlkeld would have items stolen on three occasions in the following nine months.

On 24 August, Tyerman and Bennet visited the Rev. Samuel Marsden at his home in Parramatta (Chapter 4). Having come to Australia before the establishment of the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in 1799, despite his involvement in directing the efforts of the CMS in New Zealand, Marsden remained a Director of the London Missionary Society and its appointed agent in New South Wales. Marsden introduced the visitors to Sir Thomas Brisbane, Governor of New South Wales since 1821.

The Deputation visited the factory built nearby for female convicts, but by the end of the month their focus had shifted onto Australia’s indigenous people. Although told by Australian settlers (including Marsden) that earlier attempts to convert and civilise Aboriginal people had demonstrated it to be a hopeless endeavour, Tyerman and Bennet pointed out that the same sentiment had been expressed about the Khoesan peoples of South Africa forty years earlier, among whom there were now thousands of Christians (Chapter 2 & Chapter 3):

The Hottentot and Negro have proved themselves men, not only by exemplifying all the vices of our common nature, but by becoming partakers of all its virtues; and that the day of visitation will come to the black outcasts of New Holland also, we dare not doubt.21

By 4 September, they were convinced that missionary work should be undertaken in Australia in the same way as it had been in the islands, preaching the gospel to people in their own language. While Aboriginal people had been able to pick up a few phrases in English ‘in mere common-place intercourse with Englishmen’:

if we wait till they can hear and receive the words of eternal life in any other audible sound than their own, twenty generations may pass over this land of darkness and the shadow of death, before the true light shine upon it; or, which is more probable, the whole aboriginal stock may be extirminated (like the American Indians) by the progress of colonization.22

Although an Anglican school in the colony was in the process of teaching seven Aboriginal boys while a Methodist school taught seven girls, they asked:

But what are these out of three millions? One Missionary, learning the language of one tribe, might be able to preach the simple truths of salvation to hundreds and thousands…23

No one, from what they could tell, had made any real effort to attempt to learn Australia’s Aboriginal languages.

Over a dinner at Marsden’s house on 16 September, they sounded out Governor, Brisbane and the colony’s senior administrators, receiving a degree of support for ‘any prudent measure which might be adopted for ameliorating the condition of the aborigines’. 24 They were told many tales about Aboriginal people, and Tyerman and Bennet’s lobbying efforts, encountered a great deal of resistance, noting that ‘many people who ought to know better are incurably convinced that the New Hollanders are incurably stupid’.25

They were even told that a prominent land owner at Bathurst had publicly declared that ‘the best use which could be made of “the black fellows” would be, to shoot them all, and manure the ground with their carcases’.26

A Government Jail Gang, Sydney N.S. Wales

Image 16 in Views in New South Wales and Van Diemens Land : Australian scrap book 1830, by Augustus Earle. Published in London by J. Cross 1830.

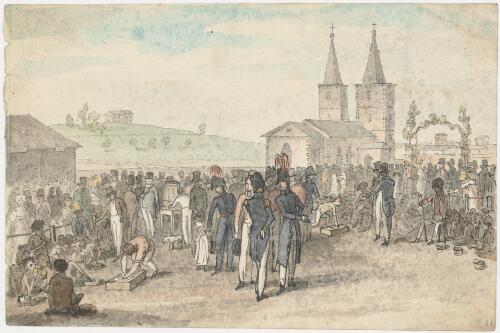

Natives of New South Wales as Seen in the Streets of Sydney

Image 10 in Views in New South Wales and Van Diemens Land : Australian scrap book 1830, by Augustus Earle. Published in London by J. Cross 1830.

Rev. Samuel Marsden's Parsonage at St. John's Parramatta, c. 1860

A copy by Isable Mary Flockton of a drawing by E. Thomas, 1909.

For Tyerman and Bennet, opposition to missionary work among settlers must have been familiar and recognisable from other colonial settings, not least South Africa (Chapter 2 & Chapter 3). Such comparisons were also evidently apparent to others with experience across colonial worlds. At a Missionary Meeting of the Wesleyan Church in early October, the recently appointed solicitor-general of the colony, John Stephen, defended preachers in the West Indies ‘from the cruel calumnies of slave-holders and slave-drivers there’, having previously worked as an attorney in Basseterre, Saint Kitts and Nevis.27

On 18 October 1824, Tyerman and Bennet met with Governor Brisbane and recommended that Lancelot Threlkeld be appointed as missionary to the Aborigines at the new colony being formed at Moreton Bay on the Brisbane River (Threlkeld had originally planned to return to England to find a wife, but since arriving in New South Wales had met and arranged to marry Sarah Arndell, the daughter of Thomas Arndell, Assistant Surgeon with the first fleet). Tyerman and Bennet had recently met an Englishman who had been wrecked and lived at Moreton Bay, who told them the people were more numerous and ‘of a superior order, to the wretched vagrants here, who are degraded below their original wretchedness by their unhappy intercourse with Europeans’.28 On his departure, after two years living among them, he had been given a fishing net and a basket by an old man, so that he could feed himself where he was going.

The Governor seemed to think that in addition to being a missionary, Threlkeld might act as chaplain at the new settlement, but when told Threlkeld was not a Minister of the Church of England, his attitude seems to have cooled. No space was found for Threlkeld on the ships going to Moreton Bay, and in December Saxe Bannister, the recently appointed Attorney General, told Threlkeld that they had ‘strong enemies behind the curtain’.29

On 28 December, the anniversary of the arrival of the colony’s previous Governor, Macquarie, Tyerman, Bennet and Threlkeld attended the feast at Parramatta, arranged for the colony’s Aboriginal people, around 400 of whom attended. Some wore red ochre and white clay on their faces as well as necklaces of reed and kangaroo teeth. They were served roast beef and plum pudding, as well as bread and soup, washed down with half a pint of grog.30

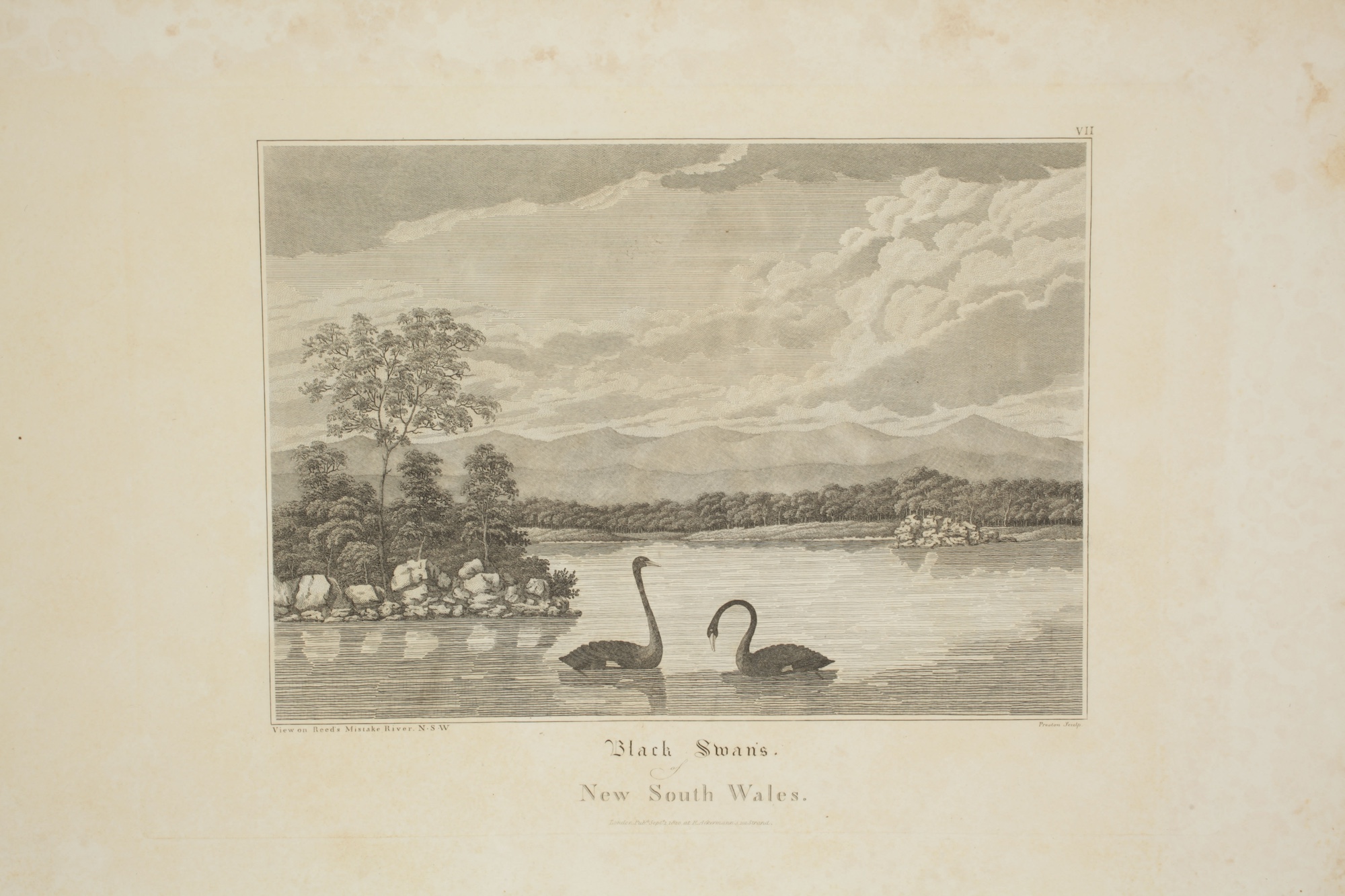

With a mission at the new colony at Moreton Bay (Brisbane) ruled out, Tyerman and Bennet looked for an alternative location, settling on Reid’s Mistake, near Newcastle ‘where the natives were numerous and where the fishing tribes could obtain a plentiful supply of fish from Lake Macquarie’.31 On 14 January 1825, they sailed around ten hours north from Sydney to see this location, returning four days later to ask the Governor for his approval. On 24 February 1825, Tyerman and Bennet arranged for their instructions to Threlkeld to be printed and circulated in New South Wales. This stated:

As a knowledge of the language of the Natives must be regarded as essential to the success of your Mission, you will deem it your duty… to be using your best efforts to acquire it; while it will greatly facilitate the progress of your work, to make yourself familiar with their customs, superstitions and habits.32

Black Swans, View on Reed's Mistake River, New South Wales

Plate VII from James Wallis (1821) An Historical Account of the colony of New South Wales

Special Collections, the University of Newcastle, Australia, Library

Land was set aside in trust for the mission, and in March Threlkeld returned to Newcastle together with his brother-in-law. After several days of rain, they walked to the place settlers called Reid’s Mistake and spoke with local Aboriginal people about their plans. Returning to Sydney, Threlkeld waited for the arrival of his three daughters from Tahiti, but when they did not arrive in April, returned to establish the new mission in May 1825.

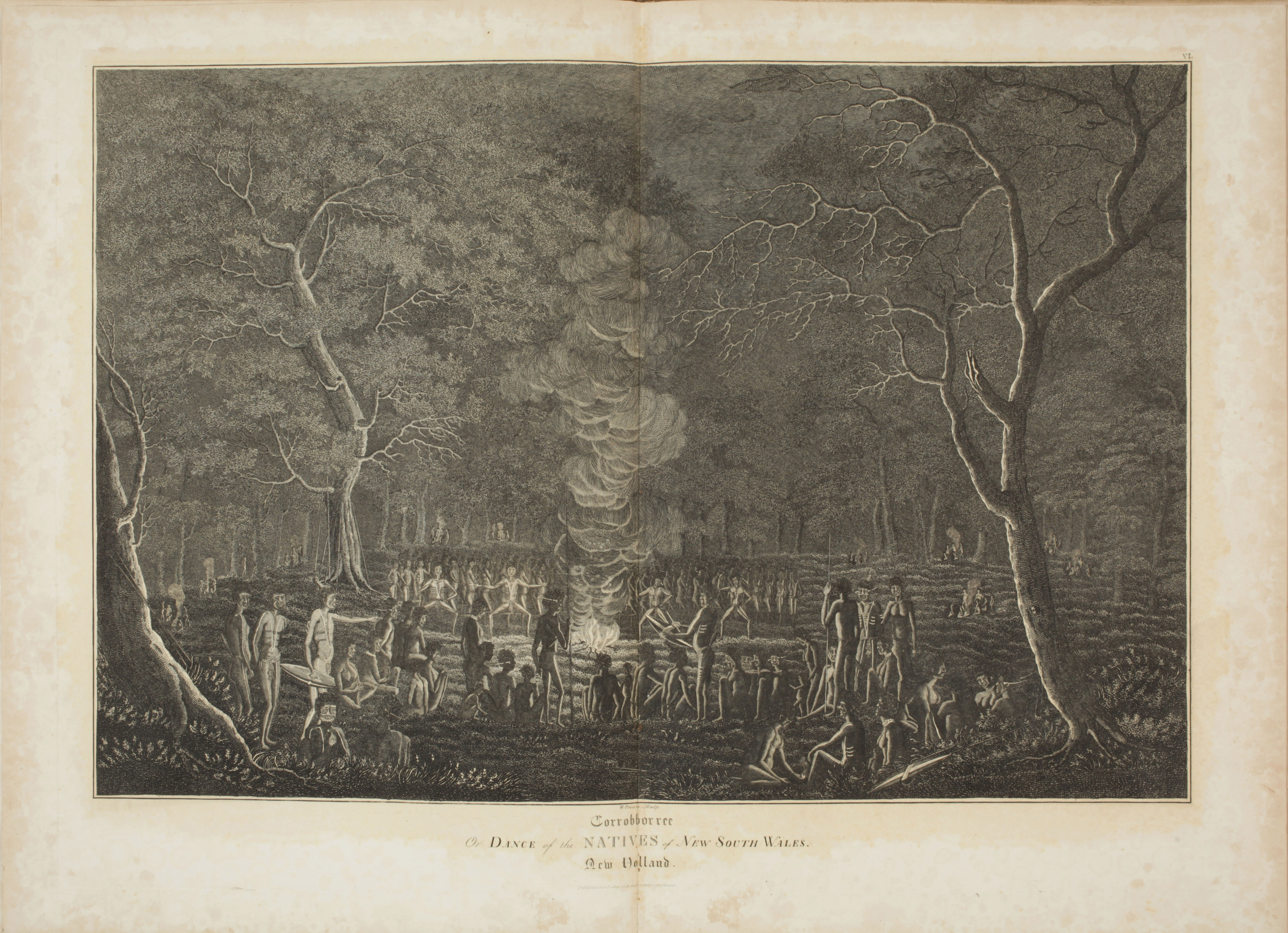

Corrobbore or dance of the natives of New South Wales

Plate VI from James Wallis (1821) An Historical Account of the colony of New South Wales

Special Collections, the University of Newcastle, Australia, Library

Threlkeld’s arrival seems to have been welcomed by the Aboriginal population, who invited him to a dance to celebrate.33

After nearly ten months in New South Wales, Tyerman and Bennet arranged to leave in June 1825, with the intention of going on the Society’s missions in Asia. Their stay had been much longer than anticipated, but they felt that ‘circumstances, which appears to be openings of Providence to direct our attention to the perishing and utterly neglected natives of this county, have detained us till this hour’.34

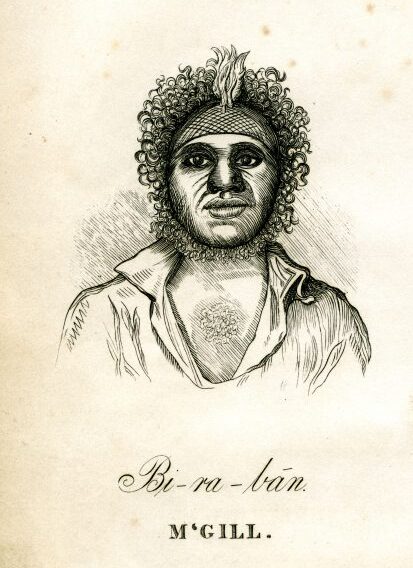

On 21 May 1825, Threlkeld wrote in his journal about ‘a trusty native who speaks good English’. On 26 May the same man took him to a suitable location for the mission, a place name recorded by Threlkeld as ‘Bad debah’ (Bahtabah, now part of suburb of Belmont in the City of Lake Macquarie).35

This was the start of a relationship that laid the foundation for Thelkeld’s subsequent work in Australia. The man in question was known as M’Gill (possibly an anglicisation of Magal) and had spent some of his childhood at the military barracks at Sydney.36 He may have worked at the penal colony at Port Macquarie, but had returned to the Newcastle area by the time Threlkeld arrived. It seems likely that M’Gill directed Threlkeld to establish the mission on land of which he was a traditional custodian.

Life for Aboriginal people in New South Wales was extremely difficult in the early nineteenth century. Between the many male convicts, who preyed on Aboriginal women and girls, and the settlers, keen to exclude Aboriginal people from their grants of land, there were many dangers and very few legal protections. Magistrates were frequently the very same settlers with whom they were in conflict. Having worked as a ‘bush constable’, M’Gill was no stranger to the violence of the young colony and he seems to have deliberately cultivated Threlkeld as an advocate for his people, while teaching him his language.

When Threlkeld witnessed an Aboriginal burial shortly after his arrival, he was asked not to tell anyone the location of the grave, since they feared a white fellow would come and take the deceased woman’s head away. Threlkeld connected this to the Maori heads he had seen for sale in Sydney, part of the trade for guns and powder during ‘the musket wars’, but was soon to learn that there was also a trade in Aboriginal heads operating in New South Wales. By spending much of each day in conversation with M’Gill, who he referred to in later years as his Tutor, Threlkeld heard stories and rumours of the deadly violence unfolding across the colony. It was not long before Threlkeld witnessed violent acts himself.37

In December 1825, Threlkeld was alerted to the sound of an Englishman beating an Aboriginal man, who had tried to stop him abducting his ten year old daughter. When Threlkeld tried to report the assault, his concerns were essentially dismissed by the magistrates. When asked by Saxe Bannister at around the same time about rumours of Aboriginal violence in Hunter River, Threlkeld could only say that he was surprised that ‘more Whites are not speared than there are considering the gross provocation given’.38

During the first half of 1826, M’Gill left Threlkeld for several weeks. He went into the mountains to participate in a ceremony, taking with him around 60 spears that he intended to exchange for possum skin cord. According to Threlkeld, he attended a ceremony at around this time ‘which has initiated him into all the rights of an Aborigine’. Despite spending some of his early life among the settlers, M’Gill was in the process of acquiring the authority to act as a leader among his people.39

At the end of September 1826, Threlkeld and his family moved to the house that had been built for them at the place he now wrote as ‘Ba-ta-ba’, having briefly also written ‘Biddobar’. In April 1827 he arranged for the printing at Sydney of Specimens of A Dialect of the Aborigines of New South Wales; being the first attempt to form their speech into a written language. Threlkeld signs the Preface from ‘Bah-tah-bah’, and the text bears the fingerprints of M’Gill, now increasingly known as Biraban (which appears in the text as Berabahn, translated as Eagle hawk).40

By this time, Threlkeld was engaged in a difficult and protracted correspondence with the Directors of the Missionary Society in London, who had become alarmed at the extremely high costs of establishing this new mission in New South Wales – around £500 a year including clothes, tea, sugar, tobacco and fish hooks paid to Aboriginal people to work at the mission. Thelkeld found that without such inducements they were unlikely to stick around for long, given the lure of nearby Newcastle – evidently a source of plentiful alcohol.

The Directors suggested that unless the New South Wales government funded some of these expenses, as originally anticipated, Threlkeld should return to the Islands. When his bills were not paid by the Society’s Secretary in London, Threlkeld was arrested at Sydney in November 1827. Concerned at characterisations of his mission as extravagant and ultimately hopeless, Threlkeld attempted to appeal to British History, arguing in a circular he had printed in 1828, that:

It may be said, with truth, respecting the Aborigines of this land, – treat them as savages, and they will act as savages; – treat them as Men, and they will act as men. We view the conduct of Charactacus, leading the Aboriginal Britons and opposing the invading Romans with applause, and Boadicea, queen of an Aboriginal tribe, with her eighty thousand English slaughtered by insulting conquerors with sympathy. But the Aborigines of Australia, who have no combined numbers, no political power, to render themselves respected, or rather feared, by the invaders of their country, are driven, indirectly, from their districts, as other wild beasts of the deserts, without Sympathy, when the civilized hand cultivates their soil!41

Although Thelkeld continued his language work while attempting to defend his expenditure, he was informed by a letter he received in December 1828 that the LMS Directors had decided to abandon the mission. They even subsequently instructed Samuel Marsden to place an advertisement in the Sydney Gazette, which declared that the London Missionary Society was discontinuing the Mission at Lake Macquarie, as well as their connection with Threlkeld. Ultimately, the new Governor of the colony, Darling, agreed to support Threlkeld’s mission, although it was relocated to land Threlkeld was granted in a personal capacity on the other side of Lake Macquarie. It became known as the Ebenezer Mission and continued until 1841.

Portrait of Bi-ra-ban or M'Gill

Drawn around December 1839 by Mr Alfred T. Agate during a visit to Threlkeld at Lake Macquarie by the U.S. Exploring Expedition of 1838-1842.

Magil, Corroboree dance [c. 1820]

Watercolour attributed to Richard Browne (1776-1824)

Beerabahn or MacGill, Chief of Bartabah or Lake Macquarie

Lithograph by H.B.W. Allan,showing Biraban wearing a ‘king plate’ around his neck which was presented by Governor Darling in 1830, in recognition of his assistance in ‘reducing his Native Tongue to a written Language’ (Sydney Gazette, 12 January 1830, p.2).

Was the club, now at the Field Museum in Chicago, collected by Threlkeld during the short years the London Missionary Society supported his mission at Bahtabah? Threlkeld had been actively involved in collecting for the Missionary Museum in the Society Islands, so it is likely he would have continued collecting things in New South Wales. Much later, in 1851, he even took an active part in organising a missionary exhibition in Sydney.42 The ‘Tur Rursna’ does not appear in the earliest surviving Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, but given the long journey between London and New South Wales, it could have arrived soon after the catalogue was published in 1826.

Alternatively, was it collected by Daniel Tyerman or George Bennet and given to the Missionary Museum together with other items they collected during their deputation? George Bennet returned to Britain in 1829 (Tyerman died in Madagascar in July 1828) and is known to have given a spear thrower, club and shield from coastal New South Wales to the Sheffield Literary and Philosophical Society (established 1822) as well as a’ Wooden Instrument used by the Aborigines of New Holland, to assist in throwing their Spears’ to the Leeds Philosophical and Literary Society (established 1820).43 Might the club have been collected by Tyerman and Bennet, and only subsequently connected with the term ‘Tur Rursna’?

It is hard to be sure of the ultimate origin of the club, but the inclusion of the Aboriginal term Tur Rursna in the later version of the catalogue, published around 1860, remains the best clue we have. The Cuming family collection, assembled in London from 1806 onwards, includes a boomerang acquired around 1840 with an attached label that reads:

TUR-RUR-MA called by Europeans Boomerang. When thrown into the air, it revolves on its centre and returns, forming a circle in orbit from and to the thrower.44

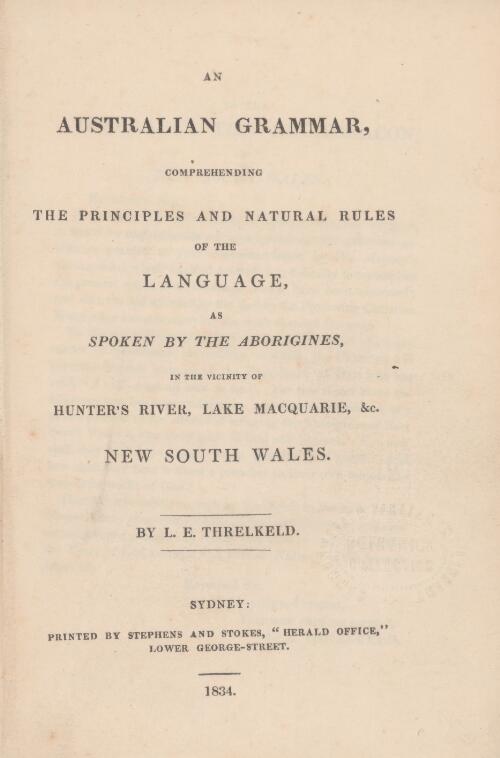

The term ’tur-rur-ma’ had, by then, featured in a list of common nouns given in An Australian Grammar, published by Lancelot Threlkeld at Sydney in 1834. There it was described as:

An instrument of war, called by Europeans Boomering, of a half moon shape, which when thrown in the air, revolves on its own centre, and returns forming a circle in its Orbit from and to the thrower, to effect which it is thrown against the wind; but, in war it is thrown against the ground which it strikes in its revolution and rebounds apparently with double violence, and strikes at random some distant object, and wounds severely with its sharpened extremities.45

Detail of Australian Club at the Field Museum, Chicago

‘L. M. Socy’ was written in pencil on the club – visible here

© The Field Museum, Image No. 272363_detail2, Cat. No. 272363, Photographer Ellen Bushell

Detail of listing for Catalogue of the Missionary Museum

Including Fuller’s pencil marks, indicating he thought he owned this item.

Published around 1860 by Reed & Pardon

Bishop Museum Library

Given the closeness of these texts, it seems likely that the information written on the Cuming boomerang came from Threlkeld’s Grammar. Interestingly, a list of names of common places in the same text includes ‘But-ta-ba’ with the meaning given as ‘The name of a hill on the margin of the lake’. Threlkeld’s introduction to the Grammar makes the case for the kind of detailed linguistic work he was doing with Biraban, partly by including a list of what he calls ‘Barbarisms’ – words pretending to be of Aboriginal origin, but which have likely arisen out of misunderstanding:

| Barbarism | Meaning | Aboriginal proper word |

| Boomiring | A weapon | Tur-ra-ma. A half moon like implement used in war. |

| Waddy | A cudgel | Ko-tit-ra |

| Woomerrer | A weapon | Ya-kir-ri. Used to throw the spear |

| Kangaroo | An animal | Ka-rai. Various names |

While whoever wrote the label for the Cuming Museum had almost certainly seen Threlkeld’s Australian Grammar, this doesn’t necessarily mean it was unrelated to items in the Missionary Museum. In 1839, Henry Syer Cuming wrote to the LMS Directors complaining about the miserable state of the Missionary Museum, offering his services to help in arranging the museum and identifying the localities from which items came if they would remunerate him for his services.46 Did he acquire a boomerang for his personal collection in return for his curatorial services, and was it through consulting the Society’s library, containing linguistic works by their former missionary Threlkeld, that he discovered the term Tur-rur-ma?

It might seem unlikely that Threlkeld would have sent his publications to London given the circumstances in which he was so acrimoniously and publicly dismissed. However, in 1830, William Ellis, who originally left England for the Pacific with Threlkeld in 1816, was appointed Assistant Foreign Secretary of the Missionary Society in London, and in 1832 became its Chief Foreign Secretary (Chapter 13).

Despite having fallen out with the Society’s Directors, Threlkeld appears to have remained on friendly terms with Ellis, asking him to show the Missionary Museum to several friends visiting London.47 In 1838, having recently been involved in establishing an Auxiliary society to raise funds for the Society in Australia, Threlkeld suggested that William Westbrooke Burton, a judge at the Supreme Court of New South Wales returning to London on leave, visit the Missionary Museum, where:

My former colleague the Revd Willm Ellis the Foreign Secretary to the Society will feel much pleasure in giving explanations respecting the many curious articles to be seen at the Society’s Museum.48

On 23 May 1840, Threlkeld wrote to Ellis from Ebenezer on Lake Macquarie, suggesting that he was making up ‘a packet for the Directors &c &c which I hope to get conveyed by some Captain to the Rooms’. Did this packet include Aboriginal weapons, or did it just include his texts on Aboriginal languages, printed at Sydney?

At the end of the Annual Report of the Mission to Aborigines, Lake Macquarie for the year 1839, Threlkeld offers a comparison of the dialects spoken by Aboriginal people, which suggests that ‘Tur-rur-ma’ may have been quite a localised term, with even people living inland from Newcastle at Manilla River using a different term:

| Lake Macquarie Inlet | Manilla River | *Swan River | *King George’s Sound | English |

| Tur-rur-ma | Pa-run | Koilee | The Boomerang | |

| * Dialects taken from a recent work entitled “Australia, an appeal to the World on behalf of the younger branches of the family of Shem.” | ||||

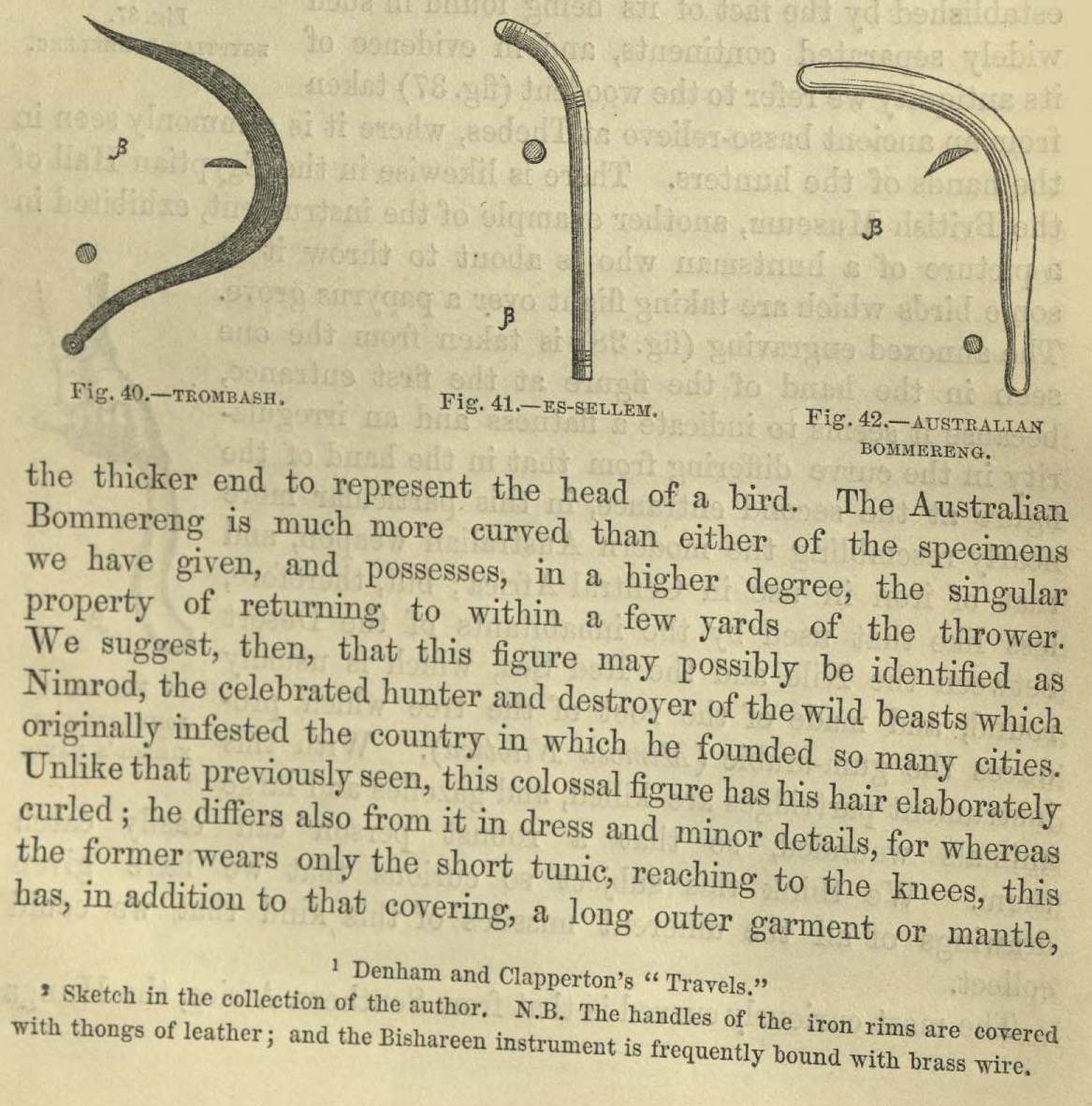

In 1854-55, Threlkeld, then Minister of the Mariner’s Church at Sydney, published a series of ‘Reminiscences’ in The Christian Herald. One, published on 31 March 1855, went under the title Warlike Implements, the Tur-rur-ma, or Boomerang.49 Commenting on the biblical prophecy that ‘The nations shall beat their swords into plough-shares, and their spears into pruning-hooks’,50 Threlkeld pointed out that the indigenous people of New South Wales formerly had no metal weapons. The text then describes:

an instrument of warfare called Yir-ra, in reality, a very simple wooden sword. At first when I saw one, I mistook it for a Boommerang, the shape in the blade being very much like that weapon. There was, however this difference, the Boommerang is alike at both ends, the wooden sword has a handle at one end with a bend contrary to the blade.51

Threlkeld draws attention to an image recently published in Joseph Bonomi’s (1852) Nineveh and its Palaces (Figure 42). This he states:

is not the Australian Bommereng, but the Australian wooden sword. The difference of shape appears to be only an accidental circumstance arising from the natural growth of the tree whence the wooden sword is taken.52

Threlkeld comments on the term ‘Boomerrang’, suggesting ‘The Orthography of this barbarism, for it is not an aboriginal term, but like many others, is a pure invention palmed upon the Blacks, as belonging to their classic lore’. Instead, Thelkeld suggests that ‘the proper aboriginal name’ is Tur-rur-ma, a term he almost certainly learned from Biraban.

It seems likely that Tur Rursna as it appears in the catalogue of the Missionary Museum is either a misreading of ‘Tur-rur-ma’, written onto a label, or else is one of Threlkeld’s earlier attempts at transcription – like the many different ways in which he wrote the place name Bahtabah.

Threlkeld’s Reminiscences suggest that the club now at Chicago’s Field Museum is not in fact a Tur-rur-ma, since it clearly has a handle at one end. Neither does it appear to be a Yir-ra, or wooden sword, since its angular profile is unlike the image he identifies as one, nor is it like other early examples recently identified in British museum collections.53 While we may never definitively know the ultimate origins of this artefact, we can be fairly certain that these words, translations from a living and spoken Aboriginal language into a written form, arose from the friendship Biraban established with Threlkeld on 21 May 1825.

Cover Page of An Australian Grammar by L.E. Threlkeld

Printed at Sydnet in 1834

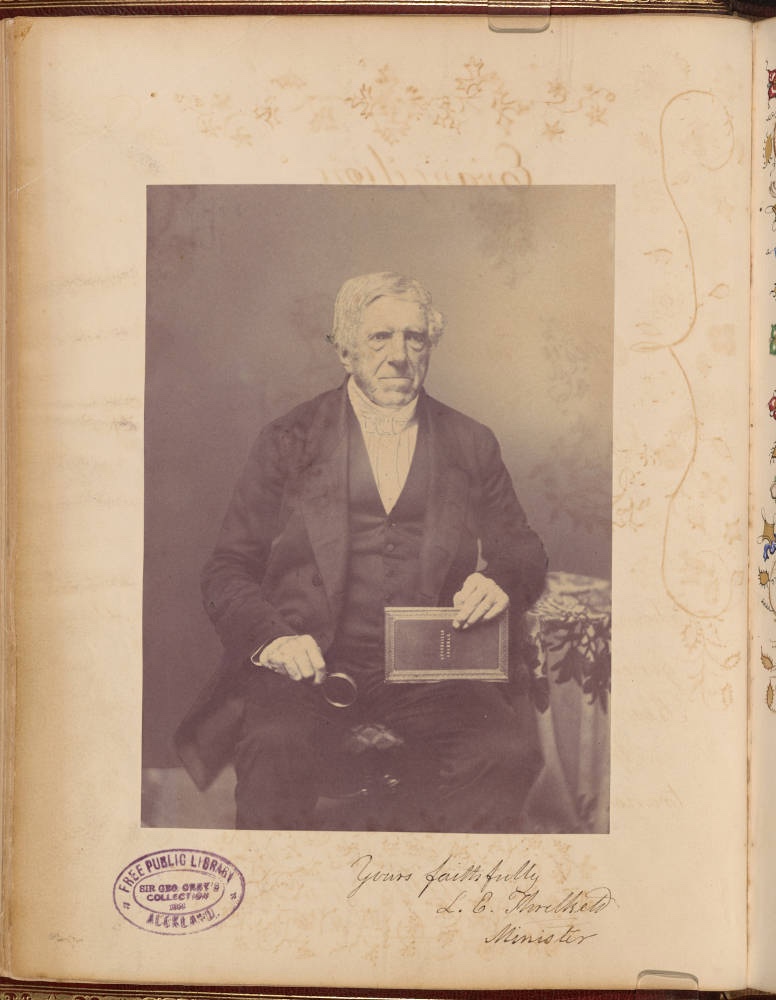

Photographic portrait of Lancelot Threlkeld, c. 1857

Threlkeld hold his Australian Grammar in his left hand.

Image 10 in the ‘Gospel according to St Luke translated into the language of the Aborigines located in the vicinity of Hunter’s River, Lake Macquarie, New South Wales, in the year 1831, and further revised by the translator, L E Threlkeld, Minister. Handwritten at Sydney in 1857.’

Detail of 'Nineveh and its Palaces' by Joseph Bonomi, 1852

Showing Figure 42 on p. 136, labelled as an Australian Boomerang

Acknowledgements

I am extremely grateful to Gaye Sculthorpe for pointing out that the club is not what Threlkeld called a ‘Yir-ra’, based on her recent work, for providing information on Bennet’s gifts of Australian items to the Sheffield Literary and Philosophical Society, as well as for connecting me with Daniel Simpson and Eleanor Foster who were working on related areas. I am extremely grateful to Danny for pointing out the use of ‘Tur-rur-ma’ in relation to the Cuming Museum boomerang, now at Saffron Walden, as well as within Threlkeld’s linguistic work. I am grateful to Eleanor for sharing her dissertation, and for her generous acknowledgement of my prior work on this club.

In the more distant past, I spent the best part of 2003 in Australia, where I learnt a great deal about Australian Aboriginal life from Nicolas Peterson, as well as Howard Morphy at the ANU. It was during that time that I first came across Niel Gunson’s compilation of material on Threlkeld. This chapter is a somewhat late return-prestation, acknowledging the impact that the time I spent in Australia has had on my subsequent work.

Comments

This is an experiment in writing – that is intended to stretch the idea of the academic monograph.

I am keen to recognise and incorporate the input and expertise of others into the writing process, so adding comments here is one way to do this.

I would welcome any comments or feedback.

Notes

1 Lovett, R. 1899. The History of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895. Henry Frowde, Volume II. P. 627.

2 These items are now better known as maro’ura, literally meaning red belt, but in Tyerman and Bennet’s account, they simply use the term ‘maro’.

3 Tamatoa seems to have also showed the Maro ‘ura to Threlked in 1821, see Gunson, N. 20188. Manuscript XXXIII: Threlkeld’s Account of the Maro ‘Ura of Opoa, Raiatea. The Journal of Pacific History, 53:2, 180-185, DOI: 10.1080/00223344.2017.1413617 ; Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 1: 527: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=D79IAQAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA527#v=onepage&q&f=false

4 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 1: 530: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=D79IAQAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA530#v=onepage&q&f=false

5 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 36: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA36#v=onepage&q&f=false

6 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 56: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA56#v=onepage&q&f=false

7 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 58: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA58#v=onepage&q&f=false

8 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 58: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA58#v=onepage&q&f=false

9 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 74: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA74#v=onepage&q&f=false

10 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 75-76: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA75#v=onepage&q&f=false

11 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 79: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA79#v=onepage&q&f=false

12 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 80: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA80#v=onepage&q&f=false

13 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 83: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA83#v=onepage&q&f=false

14 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 85: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA85#v=onepage&q&f=false

15 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 95: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA95-IA1#v=onepage&q&f=false

16 Other ships also stopped in New Zealand on their way between Tahiti and New South Wales, so it is also possible that items were also collected on other voyages.

17 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 132: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA132#v=onepage&q&f=false

18 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 133: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA133#v=onepage&q&f=false

19 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 143: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA143#v=onepage&q&f=false

20 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 143: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA143#v=onepage&q&f=false

21 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 148: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA148#v=onepage&q&f=false

22 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 151: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA151#v=onepage&q&f=false

23 Shortly after their visit, the girls from the school ran away into the forest; Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 152: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA152#v=onepage&q&f=false

24 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 153: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA153#v=onepage&q&f=false

25 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 158: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA158#v=onepage&q&f=false

26 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 158-9: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA158#v=onepage&q&f=false

27 It is possible, but perhaps unlikely that news would have reached New South Wales of the Demerara Rebellion two months earlier, in August 1823 (Chapter 5); Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 159: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA159#v=onepage&q&f=false

28 It is possible, but perhaps unlikely that news would have reached New South Wales of the Demerara Rebellion two months earlier, in August 1823 (Chapter 5); Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 162-3: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA162#v=onepage&q&f=false

29 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.84

30 It is possible, but perhaps unlikely that news would have reached New South Wales of the Demerara Rebellion two months earlier, in August 1823 (Chapter 5); Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 170: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA170#v=onepage&q&f=false

31 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.85

32 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.178-180.

33 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.88

34 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 183: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA183#v=onepage&q&f=false

35 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.89

36 Budden, L. 2024. Biraban – A Warrior, Not a Servant. Hunter Living Histories; Univerity of Newcastle: https://hunterlivinghistories.com/2024/02/22/biraban-warrior/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=biraban-warrior (Accessed 8 March 2024).

37 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.299.

38 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.91.

39 Second Half Yearly Report of the Aboriginal Mission Supported by the London Missionary Society, L.E. Threlkeld, Newcastle, June 21st 1826: Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.206.

40 L.E. Threlkeld. Specimens of a Dialect of the Aborigines of New South Wales; being the first attempt to form their speech into a written language. Printed at the “Monitor Office” by Arthur Hill; Sydney: http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1711000

41 Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.97.

42 To L.E. Threlkeld, Junior 28 May 1851; Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.296.

43 On Sheffield collection, Gaye Sculthorpe, pers. com. 5 October 2021.

44 Megan, J.V.S. 1993. Something Old, Something New: Further Notes on the Aborigines of the Sydney District as Represented by Their Surviving Artefacts, and as Depicted in Some Early European Representations. Records of the Australian Museum. Supplement 17: https://media.australian.museum/media/Uploads/Journals/17789/57_complete.pdf

45 Threlkeld, L.E. 1834. An Australian Grammar, comprehending the Principles and Natural Rules of the Language as spoken by the Aborigines in the vicinity of Hunter’s River, Lake Macquarie, &c. New South Wales. Sydney; Printed by Stephens and Stokes, “Herald Office” Lower George Street, p.91: https://ia800209.us.archive.org/16/items/rosettaproject_awk_morsyn-2/threlkeld1834_text.pdf

46 CWM/LMS/Home/Incoming correspondence, Box 7, Folder 5 – Henry Syer Cuming to Bennet Esq. 29th April 1839.

47 Letter to William Ellis, 17 April 1837. Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.261.

48 Letter to W.W. Buron, 17 November 1838; Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.274.

49 Instalment, Christian Herald, 31 March 1855, 54; Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.68.

50 Isaiah 2:4

51 Instalment, Christian Herald, 31 March 1855, 54; Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.68.

52 Instalment, Christian Herald, 31 March 1855, 54; Gunson, N. (Ed. ) 1974. Australian Reminiscences & Papers of L.E. Threlkeld, Missionary to the Aborigines, 1824-1859. Australian Institute for Aboriginal Studies. p.68.

53 Sculthorpe, G. & D. Simpson. 2023. Will my boomerang come back? New insights into Aboriginal material culture of early Sydney and affiliated coastal zone from British Collections. Australian Archaeology, 89:2, 149-171, DOI:10.1080/03122417.2023.2214336

![Views in New South Wales and Van Diemens Land : Australian scrap book 1830 [Album view]](https://argonauts2022.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SLNSW_FL3540202.jpg)

![Item 1: Beerabahn or MacGill, Chief of Bartabah or Lake Macquarie, [1830?] / lithograph by H. B. W. Allan](https://argonauts2022.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/e17333_0001_c.jpg)