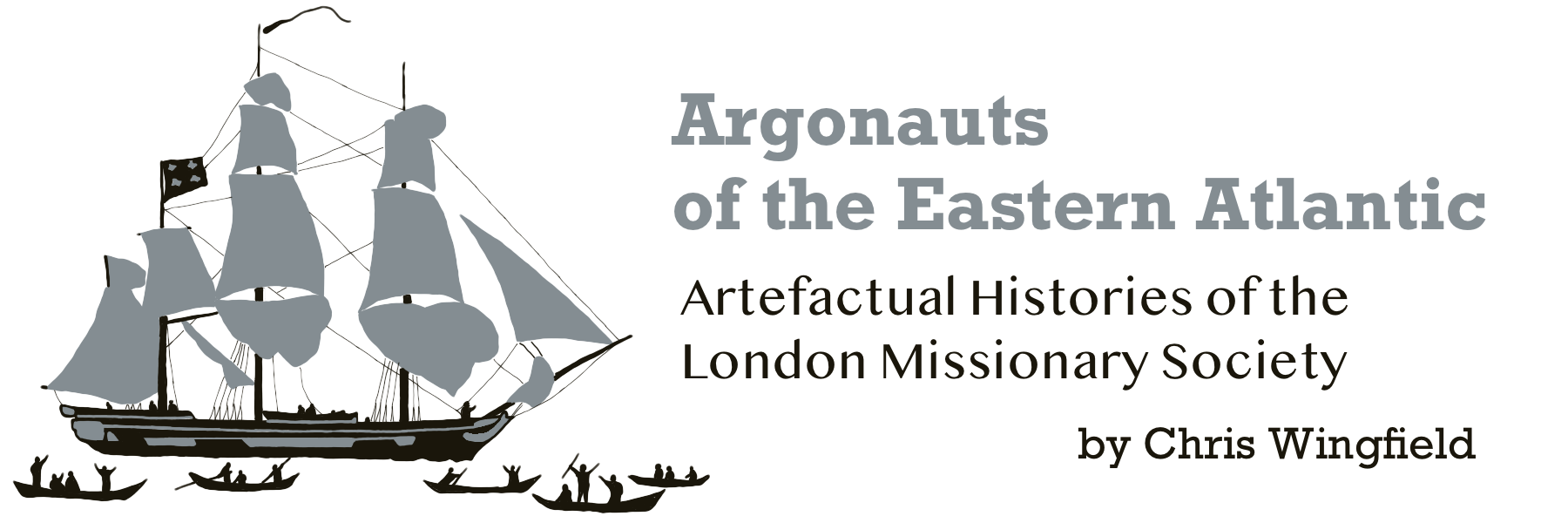

Scots Church, London, 21 November 1803

The Revd. Mr Kicherer, Mary, John, Martha

published by T. Williams, Stationer’s Court, 1 Jan 1804

From the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-779a-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

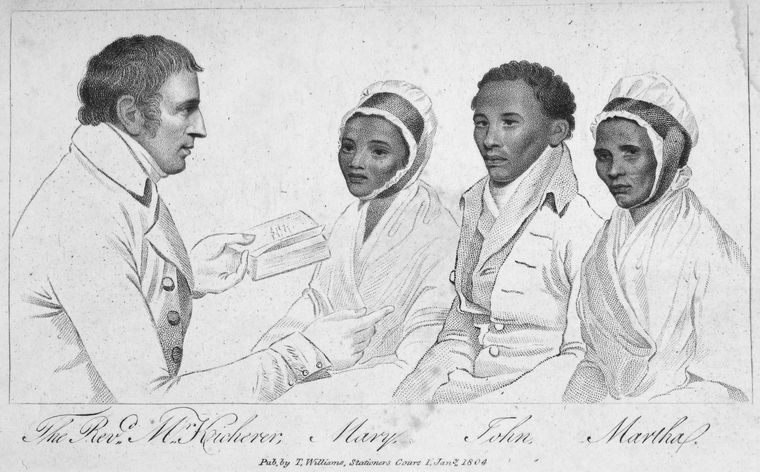

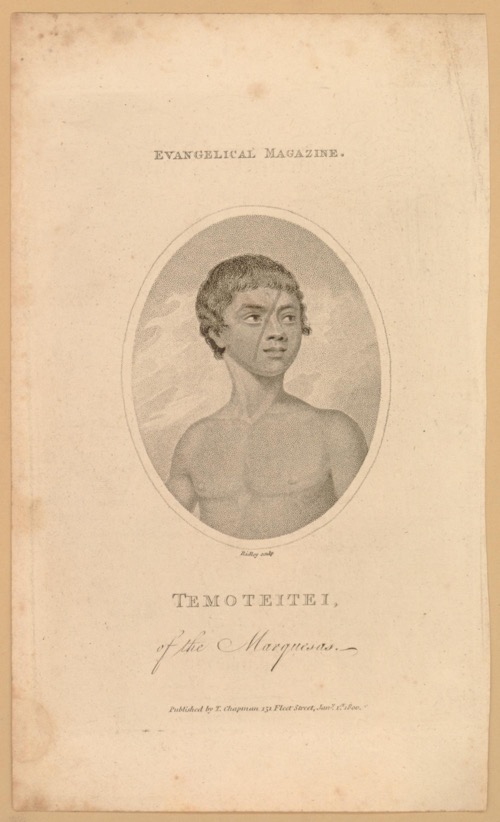

Images had featured at the front of monthly issues of this periodical since its inauguration in 1793, but had generally taken the form of miniature oval portraits of ministers, theologians and occasionally missionaries.

With one exception these had all been male, and with one other notable exception were all white Europeans – an unclothed portrait of the young Temoteitei from the Marquesas islands had been included in early 1800, following his arrival in London the previous year.[2]

Unlike earlier individual portraits, the stippled engraving from 1804 includes four people – the Dutch missionary Johannes Kicherer, preaching in profile with bible in hand, alongside three Africans who direct their attention at him. The “converted Hottentots”, as they were widely known at the time, travelled to the Netherlands with Kicherer in early 1803, visiting England at the end of the year.

While the concentration of ink and the detail falls on their faces, their dress is lightly sketched to demonstrate it is contemporary European in form. Clothing was an important signifier of civilisation and conversion – the naked Temoteitei had not converted – but the covered heads of the two women suggest modesty and respectability. Indeed, they present a significant contrast with the way Saartje Baartman was famously presented in London as the “Hottentot Venus”, a mere seven years later.

Alongside clothing, names also had the power to signify conversion. Mary, John and Martha – familiar Christian names – are inscribed beneath the image. To contemporary evangelicals these names would have recalled the episode in Luke’s Gospel (10: 38-42) when Martha busied herself with practical preparations to host Jesus, while her sister Mary sat listening to his words.

The tensions between Christ’s spiritual message and the practical arrangements needed for its transmission dominated early missionary work, so this choice of names was surely deliberate. Indeed, it seems that in South Africa Mary had previously been known as Sara and John as Klaas.[3]

John the Baptist lived in the desert on locusts and honey, preparing the way for Jesus, but was also Kicherer’s own first name, but is missing from the inscription in favour of his titles “the Revd. Mr”.

Temoteitei of the Marquesas

print at the British Museum

Originally published in January 1800 in the Evangelical Magazine

One surviving copy of this image, published online by the Ephemera Society, includes a hand-written pencil note that states:

The first converted Negroes. I saw them at Orange Street Chapel and shook hands with them all… Mary & John married.

The fact that the “converted Negroes” embodied respectable family life further added to the way they were regarded – Mary gave birth in Holland before returning to South Africa.[5]

For missionary supporters, “the appearance of three converted Hottentots” in London offered “ocular proofs of the power of Divine Grace on some of the most abject of the human race”, suggesting not only that missionary activity was worth supporting, but also that “Christianity is the most powerful instrument of Civilization”.[6]

The Revd. Mr Kicherer, Mary, John & Martha

published by the Ephemera Society as item of the Month in April 2012

A religious tract under the title The Converted Hottentots, published later in 1804, reproduced a version of the same image with Kicherer excluded, but the cheaper woodcut engraving method impacted on its quality, making the converts’ facial features difficult to make out in the smudges of ink.

The tract included a transcribed dialogue with Kicherer and the converts that took place on 21 November 1803, at the Scots Church in London, originally published in the following month’s Evangelical Magazine. It was chosen for syndication because, according to the preface, it ‘gave the highest satisfaction as to the truths of their conversion and their sincere piety’.[7]

But who were Mary, John and Martha and how did they come to be celebrated alongside a Dutch missionary in the evangelical publications of London ?

Associated with the Evangelical Magazine from its foundation, the Missionary Society began its own publishing endeavours by producing annual reports. These were initially very much along the lines of a commercial annual report – an account of activity for shareholders, accompanied by a statement of income and expenditure.

Missionary shareholders were effectively members of the society who subscribed at least a guinea a year, from whom the board of Directors was elected. The Directors constituted a monthly business meeting to supervise the work of the society’s only salaried employee, the secretary.

In 1803, however, a new publishing venture began, Transactions of the Missionary Society, which made an edited selection of of the Society’s correspondence with missionaries available in print – just over 500 pages were included in volume one.

Captain James Wilson and First Mate William Wilson (his nephew)

cover page of The Converted Hottentots

Tract XVI in the Cottage Library of Christian Knowledge

The first volume told the Society’s story from the establishment in 1795 until the end of 1802. This was prefaced by an introduction that connected this to a longer history of missionary activity stretching back to ‘the great Apostle’, Jesus Christ himself.[8] The account acknowledged the conditions provided by the Roman empire for the missionary journeys of Paul, and readers were expected to understand that the British empire offered similar opportunities. The expansion of Christianity alongside Spanish and Portuguese empires was briefly described, though it was made clear that Protestants would have done a better job.

Finally, a brief summary was given of recent work by Protestant missionaries – Danes in Greenland and India, Moravians and the Dutch in various parts of the world, and finally the English Baptists, with William Carey in India.

The focus for the Transactions then shifts to establishment of the Missionary Society in London and its initial focus on the Pacific. The Duff’s capture on its second voyage is described, as well as the abandonment of Tahiti and the way this shook the endeavour ’to its foundation’.[9] Regardless, missionary work in Tahiti continued, with a reinforcement of eight missionaries arriving in July 1801.

The account was not confined to the Pacific but also described early missionary efforts in Britain’s remaining North American colonies, subsequently Canada, as well as missionary ambitions for India. Besides the Pacific, the major focus of the Transactions was the establishment of a second missionary field in South Africa.

View from the Castle at Cape Town

painted by Lady Anne Barnard shortly after the British invasion, 1797

With thanks to Culture Connect

The Cape of Good Hope, on the tip of the African continent, had been maintained as a refreshment station since 1652 by the Vereenigde Ost Indische Compagnie (VOC), the Dutch East India company, one of the world’s first global corporations. The colony, originally centred around a VOC castle, grew as increasing numbers of Europeans settled at the Cape, taking ever larger tracts of land from its indigenous Khoe and San inhabitants. Stock and crops were raised with forced labour, including that of people enslaved at Madagascar, Mozambique, as well as Dutch colonies in Asia.

Rivals with the British in the mid-17th century, the Dutch had become allies after 1688 when the Glorious Revolution put William of Orange, a Dutch Protestant King, on the English throne. The 18th century saw the British overtake the Dutch in wealth and maritime supremacy, but in 1780 Dutch support for American rebels led to conflict with Britain that weakened the Dutch Republic.

In early 1795 an alliance of French forces and Dutch Republicans invaded the Netherlands to establish the Batavian Republic, allied with revolutionary France. Britain, then at war with France, invaded the Cape in mid-1795 to protect its shipping routes, at around the same time the Missionary Society was established back in London.

The Transactions noted that the Society’s earliest missionaries to Africa went to Sierra Leone in 1797, but war kept them on the coast, where by mid-1798 one had died and the other had been dismissed.

Although British evangelicals connected West Africa with the evils of the slave trade, they also regarded British control of the Cape as an act of providence that might open the continent to Christianity by another route. The problem was that most people in the Cape colony spoke Dutch, making it a difficult place for British missionaries to work.

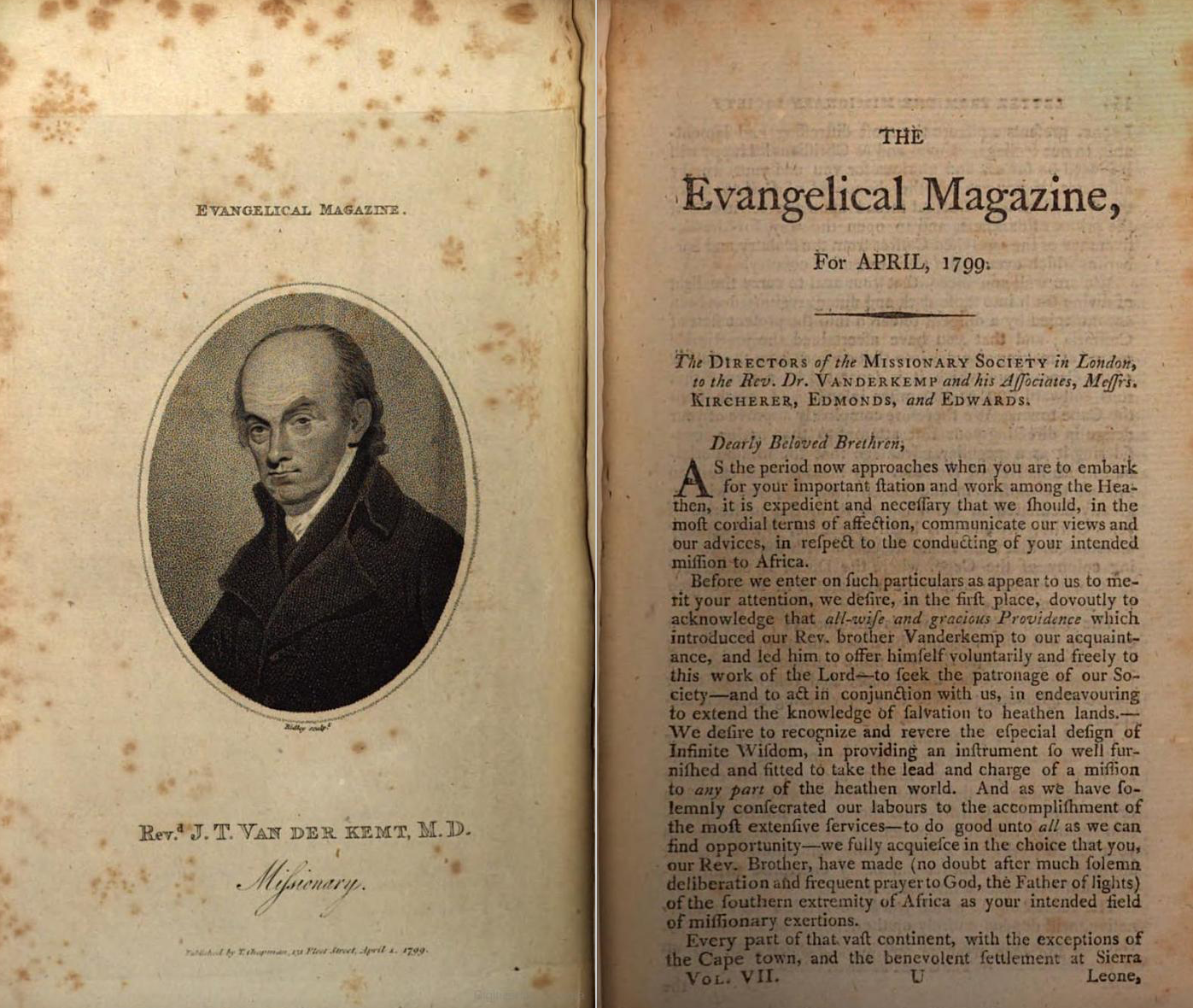

This problem appeared to solve itself when the Directors received a letter in early 1797 from Johannes Theodosius Van der Kemp, who heard about the establishment of the Society and wanted to volunteer. Van der Kemp was a fifty-year-old Edinburgh trained medic and experienced soldier who had become an evangelical Christian after losing his wife and daughter, and nearly losing his own life in a boating accident in 1791.

Like Captain Wilson before him, Van der Kemp was regarded as sent by God. Working with the Directors, he established the Netherlands Missionary Society in Rotterdam, recruiting another volunteer for mission work, Johannes Kicherer, then in his early twenties.

At the end of 1798 the two Dutchmen, accompanied by two Englishmen, John Edmonds and William Edwards, departed on the Hillsborough, a convict ship bound for Botany Bay, part of the same convoy of ships as the Duff on her calamitous second voyage.

Portrait of Rev. J. T. Van der Kemp

published in the Evangelical Magazine, April 1799

The arrival of these missionaries at the Cape, and the support offered by the British acting governor, General Francis Dundas, generated a reaction among local Christians that led to the formation of the South African Missionary Society.

While they were in Cape Town, however, the missionaries met three men who literally changed the direction of missionary activity in South Africa. They are reported in the Transactions as ‘Boscheman Captains’ by the names of ‘Vigilant’ and ‘Slaporm’ (slack-arm) and ‘Orlam’ (a term used to describe creole people of indigenous descent, of whom he seems to have been one).

In a letter sent to London in May 1799, Van der Kemp records their names as T’Karoe and T’abekom and ‘Orlam’ as a member of the Coranna nation was called T’zijib, presumably transliterations of their Khoesan names.[10]

When they asked for some ‘good persons’ to ‘be sent among them’ this was interpreted as another act of divine providence and although Van der Kemp felt called to the Cape Colony’s eastern frontier, he agreed that William Edwards should go with them, and if local support was insufficient, for Kicherer to join him.[11]

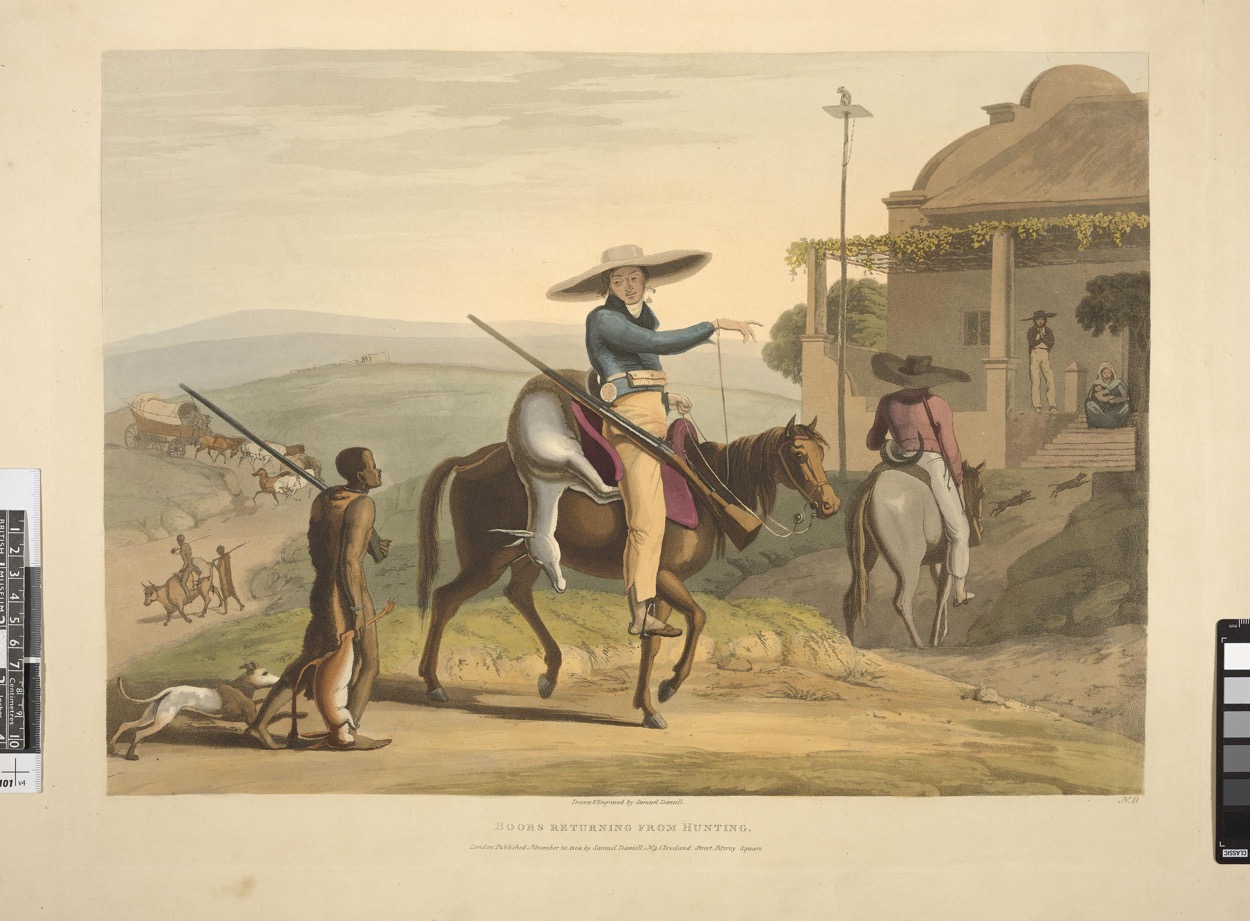

The historian Nigel Penn has called the eighteenth century northern border zone with the Cape the Forgotten Frontier. In contrast to regular pitched battles fought in the east of the Cape Colony, this porous frontier with its highly mobile population of indigenous Khoe and San made the expansion of European domination different, but no less violent.

The central institution of this expanding frontier was the commando, an armed band of farmers of Dutch descent, accompanied by their Khoe servants, who assembled for mutual self-defence. The commando had a great deal in common with what became the ‘posse’ in the American West later in the century, and then as now, when groups of armed and frightened men rode out seeking justice, seemingly defensive actions frequently became offensive actions.

South African Sendinggestig Museum

missionary meeting house established in Long Street, Cape Town in 1801 by the South African Missionary Society

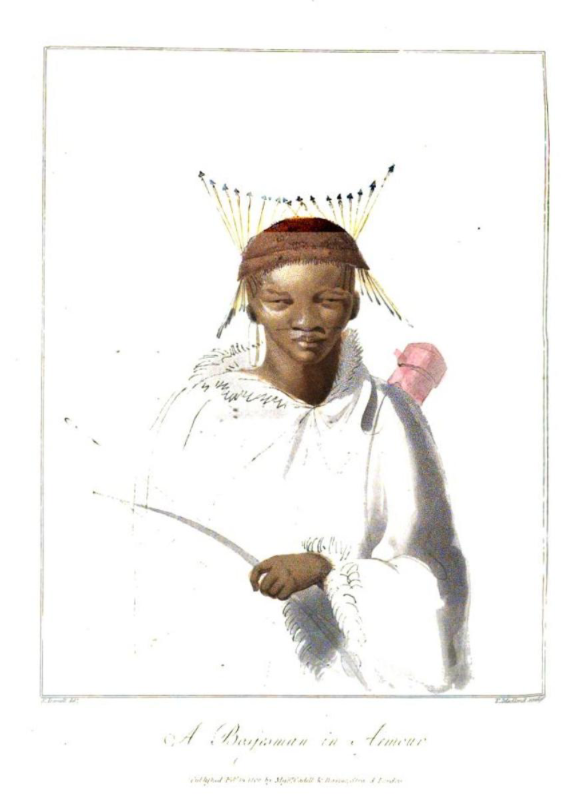

While the Cape’s cattle and sheep-herding Khoe peoples had much in common with the similarly pastoralist Dutch frontier farmers, known as trekboers, the San (a Khoe term meaning forager) or as they were widely known in the colony ‘Bushmen’, pursued a way of life that depended predominantly on wild foods. This put them into conflict with the new arrivals, whose stock consumed the limited supply of water and grass on which wild animals also depended. In addition, and perhaps more significantly, large numbers of these wild animals were killed by the guns of horse-riding incomers.

Bushman Hottentots armed for an expedition

published by Samuel Daniell January 1st 1804

Based on drawings made during the 1801-2 Truter Somerville expedition into the southern African interior

British Museum: 1913, 0129.1-30

To resist these depredations, San, armed with bows and poisoned arrows, raided pastoralist herds, prompting deadly and frequently indiscriminate commandos against them – men were shot on sight and women and children taken to farms where they were forced to work. When John Barrow was sent by the newly installed British Governor, George Macartney, to investigate in 1797, he was shocked to hear farmers boast of having killed hundreds of San.[12]

It was a genocidal conflict over the land, and for the San, literally a fight for survival.

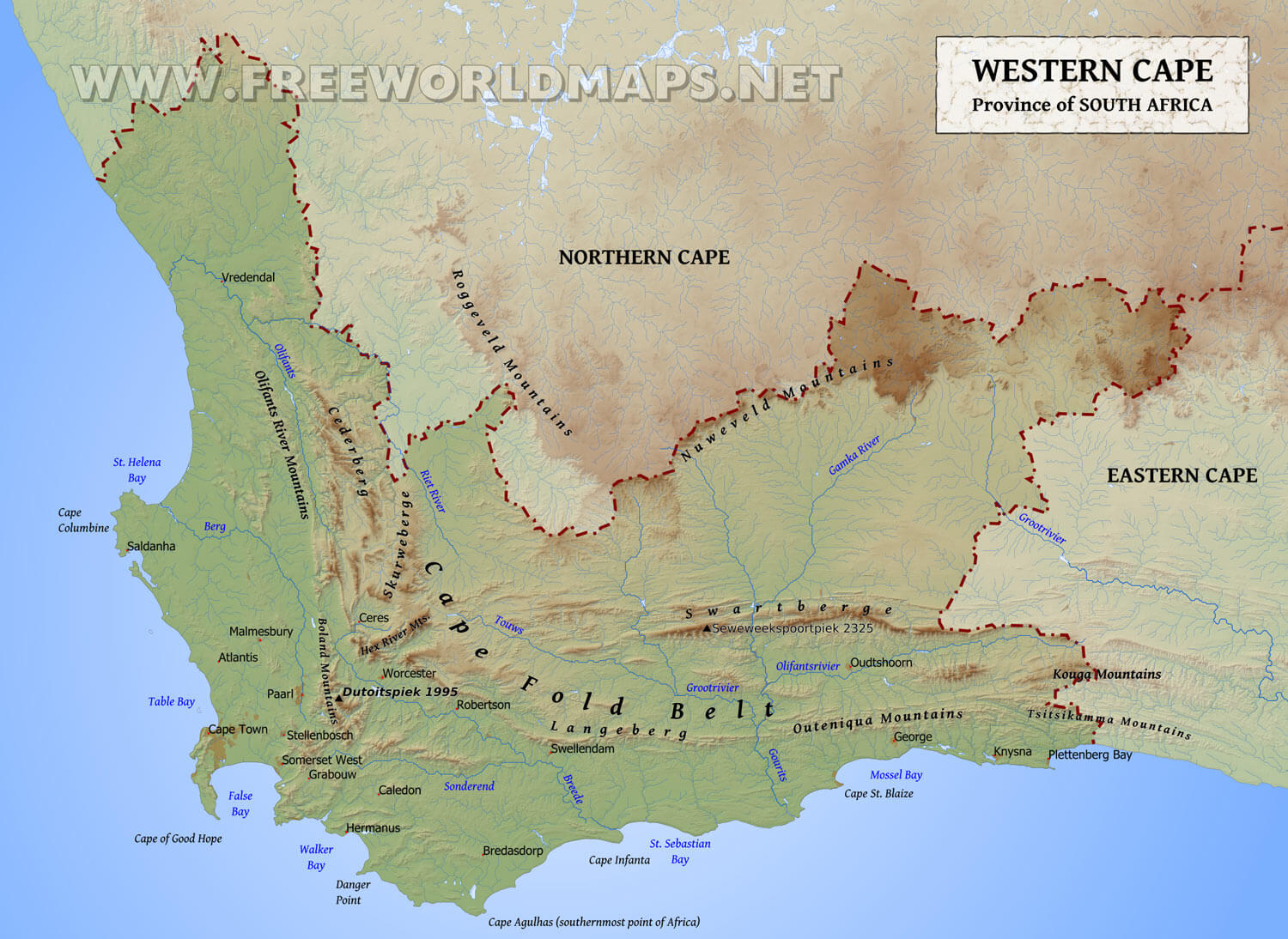

The ‘Boscheman Captains’ who met the missionaries in Cape Town came from beyond the Roggeveld, an area where the land rises to meet the high plateau of the African interior, and rain only falls during the summer – an arid zone known at the time as ‘Bushmanland’. The arrival of trekboers in the region during the second half of the 18th century initiated a cycle of violence that saw many hundreds of people killed by commandos and hundreds more taken captive.

Boors Returning from Hunting

engraving published by Samuel Daniell November 20th 1804

Based on drawings made during the 1801-2 Truter Somerville expedition into the southern African expedition

British Museum: 1913, 0129.1-30

In 1798 Floris Visser, a magistrate and farmer, more pious than most, travelled to Stellenbosch to propose a different way of dealing with the San. This so impressed the authorities that he was sent to meet the Governor in Cape Town, who agreed to his proposals. Livestock would be given to them, along with rights to land where they and their children would be safe.

The idea was that instead of being opposed to colonial expansion, the San should, through the acquisition of property, become part of its pastoral economy, hastening their ‘civilisation’. Macartney encouraged Visser to send San leaders to Cape Town to meet him, where he presumably intended to charm them into cooperating.

Visser had proposed that ‘captains’ be appointed among the San and given a copper headed staff and brass gorget as a sign of their status – an early method of indirect rule that was partially successful among Khoe groups in the Colony.

One of the ongoing issues that exacerbated the conflict was that it was very hard to identify recognised leaders with whom to negotiate. The egalitarian nature of San society made it hard for anyone to put themselves forward and receive consistent support from their communities.

In early 1799, despite the departure of Governor Macartney on health grounds, Visser recruited 187 San men and 284 women and children who were prepared to agree to his proposals, including a number willing to work on Dutch farms, in part because they were literally starving.

T’Karoe, T’abekom and T’zijib agreed to go to Cape Town following a presentation of gifts that included livestock, beads, knives, tobacco, mirrors, flints and tinder-boxes. According to Van der Kemp, they had been interested by Visser’s prayers and hymns, and wanted to know more about the settlers’ God. It is likely that they had also heard about the Moravian mission at Bavian’s Kloof (now Genadendaal) which had been reestablished in 1792 and was rapidly becoming a refuge for dispossessed Khoe within the colony.

Kaptein Koopman's staff

from Genadendal in 1814, showing the British coat of arms

Map showing geographical features of the Western Cape

locations of CapeTown, Stellenbosch and the Roggeveld Mountains marked

Without explaining any of this background, the Transactions picked up the story with the missionaries travelling to the inland settlement of Roodezand, guided by Bruntjie, a Khoe elephant hunter from Baviaan’s Kloof. From there, Van der Kemp and Edmonds travelled to the East in their wagon with Bruntjie, while Kicherer and Edwards waited for a promised wagon to take them to ‘Bushmanland’.

They managed to recruit a local man of Dutch descent by the name of Kramer, as well as Willem Fortuin, of mixed Khoe descent, as well as his wife who spoke ‘the Boschemen’s language’, to join them later – the Transactions declared that ‘so mercifully the Lord seemed preparing their way unto the Gentiles’.[13]

From Roodezand, the missionaries travelled for a week to Visser’s farm, and from there another two weeks into ‘Bushmanland’, accompanied by five wagons, sixty oxen, two hundred sheep and around fifty people. There they established a small missionary settlement at what they named Blydevooruitzigt Fontein, which the Transactions translated as Happy Prospects Fountain. Its two springs gave it the potential for permanent settlement, including a garden planned to recall a plentiful Eden in the midst of this arid land.

When the farmers left, Visser’s son stayed to help and his knowledge of |Xam, the language spoken the local San, was invaluable until Fortuin and his wife arrived. Other linguistic tensions plagued the mission, however, and when San joined the settlement, they were divided into two groups – one to learn English with Edwards and the other Dutch with Kicherer. Not long afterwards Edwards took his ‘English’ congregation to live separately.

By November 1799, Kicherer reported in a letter quoted in the Transactions that they had between 30 and 40 ‘Bushmen’ living at the mission, although he noted in a slightly exasperated tone that numbers had been higher, but ‘they wander to and fro’.[14]

While there were signs of interest in Christianity among the San, Kicherer worried that many residents at the mission were more focused on his regular gifts of tobacco – a quarter pipe after attending each service.[15] Concerned about rapidly depleting supplies, Kicherer took nine San to Cape Town in January 1800 to ask for additional support from the Governor.

His letter to the Directors following his return in March, suggests he was deeply conflicted, seeking to convince himself he was doing God’s work among ‘the most savage and ferocious of all the people who are known in this country’, but constantly worrying about the meagre and extremely insecure practical arrangements on which his mission depended.[16] He described his ‘separation from civilised society’ and the distance from his family and friends as an open wound that grows every day.[17]

As a relatively young man of twenty five, he was strongly tempted to accept the offer of a post as minister to one of the settler communities in the colony. In addition, while Kicherer had been in the Cape, ‘Vigilant’, having killed ‘Orlam’ in a fight, attempted to help himself to the mission’s sheep.

Portrait of J.J. Kicherer 'Missionary to the Boscheman'

published in the Evanglelical Magazine

When Kramer tried to stop him ‘Vigilant’ lunged at him with a knife, but a young San woman threw her kaross, or fur cloak, between the quarrelling men, saving his life. Despite his apparent initial enthusiasm for the missionaries, ‘Vigilant’ later told a local farmer who arrested him that he couldn’t abide the Dutch living in his country.

When Kicherer returned to the troubled mission with another recruit and a stronger mandate from the Governor, Edwards left to try his luck with Van der Kemp in the East of the Colony. When a group of San attempted to shoot Kicherer with poisoned arrows, he decided to relocate the mission to the Zak River, nearer the Colony, where he might receive greater protection from the colonists.

At this point, the so-called ‘Bushman Mission’ seems to have shifted its focus from the San to people of Khoe descent, many of whom had lived and worked on Dutch farms and were more interested in becoming Christians.

At the end of 1800 additional missionary recruits arrived in South Africa and one of them, William Anderson joined Kicherer when he was once again visiting Cape Town.

In May 1801, less than two years after commencing the mission, Kicherer led his followers across Bushmanland to the less arid region near the Gariep, or ‘great river’ in the North, where Anderson had gone ahead to establish a mission to the Coranna, or Orlam, a Khoe group that had left the colony.

It is with a letter from William Anderson dated 6 December 1801 describing this seeming abandonment of the mission to the San that the first volume Transactions ends its account of work on the northern frontier of the Cape Colony, although quite a bit of space was also given to Van der Kemp’s attempts to establish a mission among Xhosa-speakers further East.

A Bosjesman in Armour

by Samuel Daniell. Published in Travels Into the Interior of Southern Africa by John Barrow in 1806: Google Books

In contrast to the youthful Kicherer’s relative obscurity in the first volume of the Transactions of the Missionary Society, the title page of its second volume, published in 1804, announced in capital letters that it included The Rev. Mr. Kicherer’s Narrative of His Mission to the Hottentots and Boschemen.

In March 1802, Kicherer had returned to ‘Bushmanland’ from the North, only to have his stock raided and to find venomous snake heads floating in the waterholes.

After reestablishing his former base at the Zak river, increasing numbers of Khoe arrived at the mission, and by January 1803 when he left his posting once more, there were 600 people living there, of whom 30 adults and 50 children had been baptised.

The ever restless Kicherer, concerned about his own health as well as that of his recently widowed mother, left the Cape for Europe at the very moment the Colony returned to Dutch control following the Treaty of Amiens.

News of Kicherer’s arrival in Holland with ‘three African converts’ was reported in the Evangelical Magazine and their arrival in London anxiously awaited, despite reservations from the Society’s Directors, presumably concerned at the cost of hosting them.[18]

Having witnessed responses to the San he had taken to Cape Town, Kicherer’s commitment to take converts to Europe seems to have been a fairly knowing part of his ongoing campaign to attract additional resources for the mission.

According to a preface in the Transactions, Mary, John and Martha’s desire to go to Europe was prompted by allegations made within the colony that the religion they were taught by missionaries was not the same as that of European Christians.

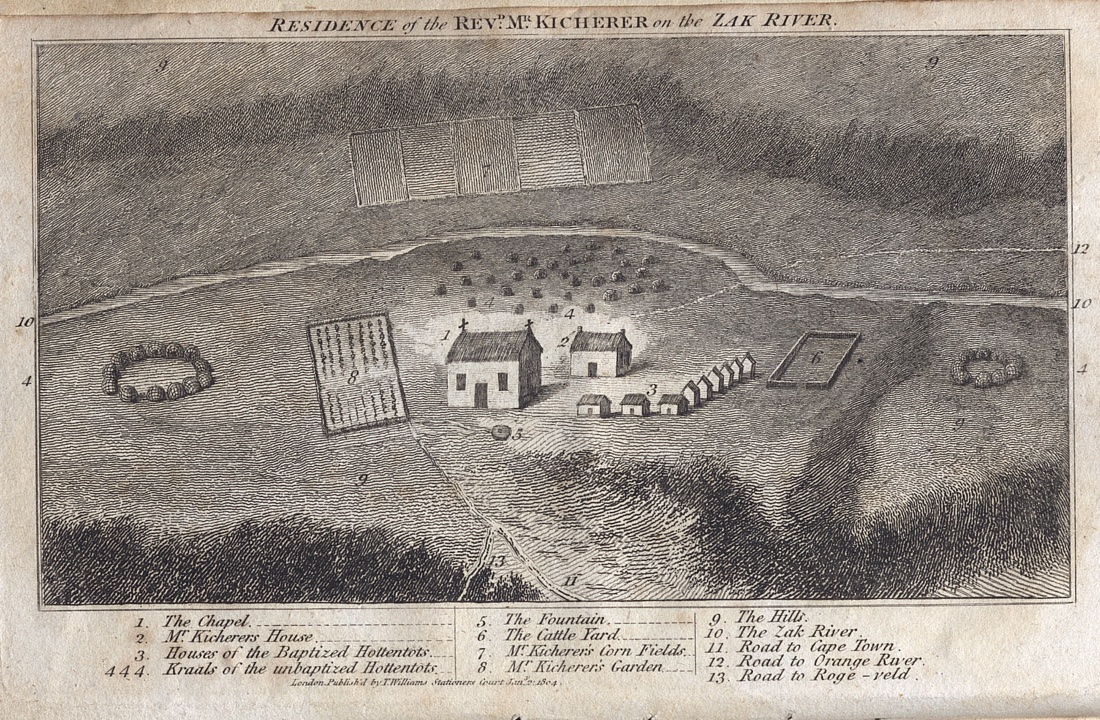

The celebrity status their presence provided Kicherer, however, induced the Directors to ask him to write an account, to literally put his name on the front page of their magazine and to commission an image of the Zak River mission based on his sketch. Kicherer became the hero of the story and while his account may not have exactly glorified his missionary work in South Africa over the previous four years, it certainly cast it in the best possible light for European readers.

Residence of Rev. Mr Kicherer on the Zak River

published in 1804 opposite the title page of Transactions of the Missionary, volume II

Council for World Mission Archive, SOAS Library

The story told by Kicherer was full of accounts of sincere conversion, but at the same time constructed a portrait of the San as ‘Wild Hottentots’ emphasising the difficulty of conducting missionary work among them, in contrast to the ‘Tame Hottentots’ of the colony. The visual distinction in his sketch map between the rectilinear houses of the ‘Baptised Hottentots’ and the circular structures of the ‘unbaptised Hottentots’ make a similar categorical distinction based on conversion.

Kicherer compared San huts to pig styes and found their practice of smearing animal fat and pigment onto their bodies disgusting. He was shocked by examples of domestic violence and infanticide, and his descriptions of the degradation of the San provided a backdrop for the ‘Providence of God’ which called them to the fellowship of the Gospel and rendered them ‘the distinguished trophies of his almighty grace’.[19]

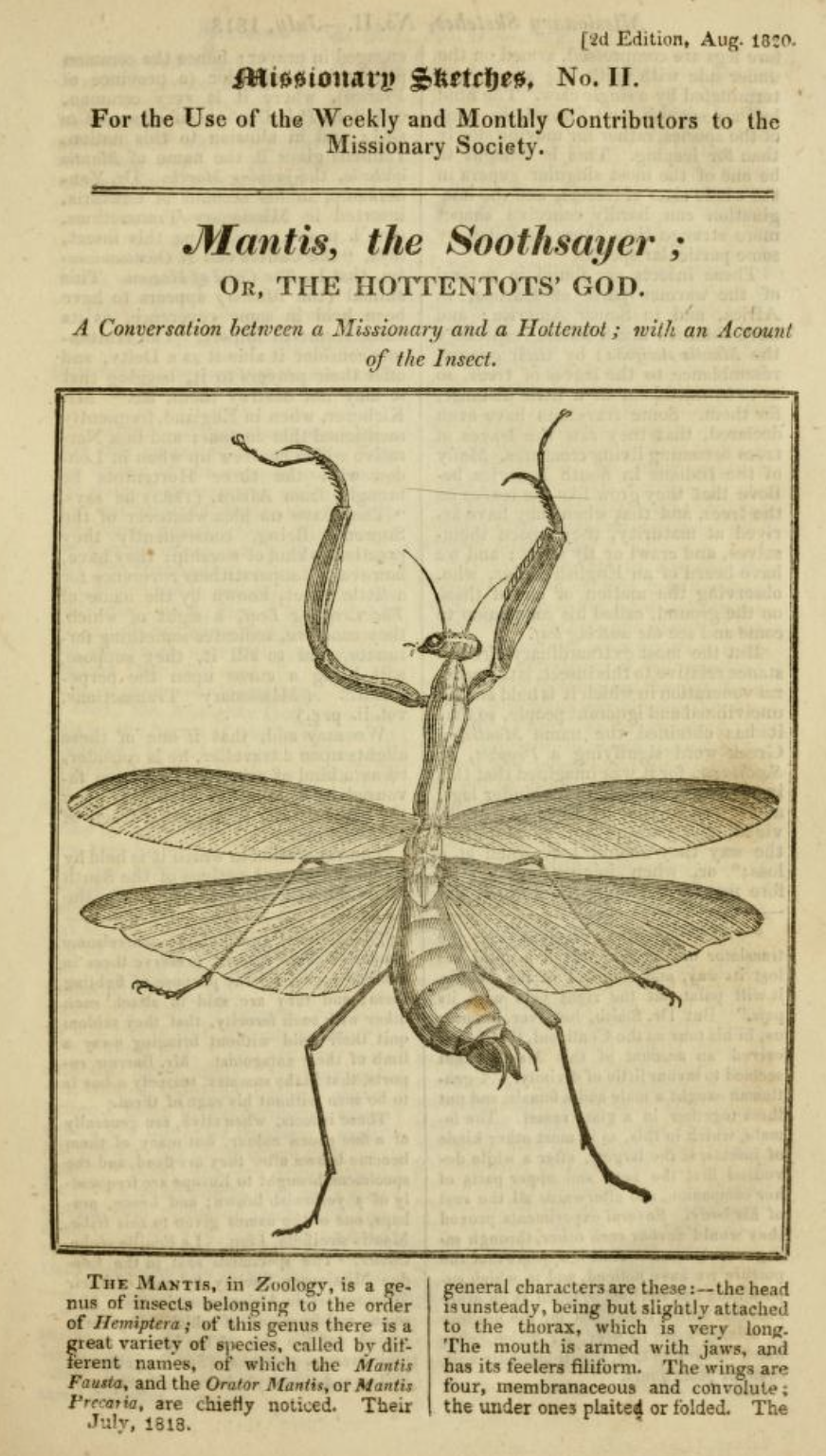

In religious terms, Kicherer suggested that the San:

have no idea whatever of the Supreme Being… practice no kind of worship’ having only ‘a superstitious reverence of a little insect known by the name the Creeping-leaf, a sight of which, they conceive, indicates something fortunate, and to kill it, they suppose, will bring a curse upon the perpetrator

An 1826 catalogue of the Missionary Museum would quote Kicherer’s words in its caption for a praying mantis that was displayed there as ‘the Hottentot’s God’, a name retained in contemporary Afrikaans.

This detail, as well as Kicherer’s account of healing ceremonies involving ‘men… employed to blow, and make a humming over the sick, which they sometimes continue for many hours together’ fits well with later descriptions of San ceremonial practices across southern Africa. Kicherer, however, found these impossible to reconcile with what he regarded as Civilisation.[20]

We can’t know what San made of the Christianity he attempted to teach them, although he noted that those who visited Cape Town compared its Calvinist Church to an ant’s nest and its organ to the sound of a swarm of bees.

Within Kicherer’s account there are, however, hints of the endemic murderous violence of the Frontier. He suggested that ‘Boschemen… when approaching a white man for the first time… appear in an agony of fear, which discovers itself by the trembling of every limb.’ [21]

Those who travelled to Cape Town were struck with dread and dismay when they saw men hung in chains for atrocious crimes, as well as when they witnessed a public execution, although Kicherer attempted to make these things object lessons in European justice as an ordinance of God.

Mantis, the Soothsayer

Published in Missionary Sketches, 1820

Naming and clothing emerge as central themes in Kicherer’s account. He describes how he gave names to the San who joined the mission, and wrote these across their shoulders in chalk. When they approached him, the first thing they did was turn to show him their backs. His regular trips to the Cape seem to have been motivated, at least partly, by attempts to get hold of European style clothes to dress his congregation, to replace the sheep skins he described as ‘filthy karosses’.

An account of Kicherer’s testimony to a congregation in London in November 1803 makes it clear that the ‘Hottentot converts’ were intended to illustrate a contrast with the way in which they were reported to have lived before conversion:

When these poor Africans are enlightened, a great change takes place in their outward conduct and appearance. Those who before were almost naked, clothe themselves with decency; – from being extremely filthy, they learn to be clean; – and from that laziness which prevailed among them while Heathens, they learn to be diligent, and to cultivate the earth for their subsistence. Thus while the gospel brings to them a spiritual salvation, it becomes also the mean of civilising, we might almost say, of humanising them; and this affords an additional argument for Missionary zeal.[22]

When questioned in front of a congregation with Kicherer acting as translator and mediator, there were few in London who doubted the sincerity of Martha, Mary and John’s conversion and their conviction in the saving grace of Christ. However, there seems to have been a degree of slight of hand in their presentation as the straightforward results of missionary work, alongside these accounts of ‘wild Bushmen’.

While John van Rooij called himself a ‘pure Hottentot’, both Mary, whose maiden name was Fortuin, and Martha Arendse were regarded in the Cape as ‘Bastaard-Hottentots’, the children of one Khoe parent and one enslaved Malay parent. Mary had worked at the tobacco plantation where Kicherer bought his tobacco, and left this employment to join the mission. Martha had worked as a servant for a Dutch family, but left to join the mission where she was employed by Kicherer as his house-keeper.

Familiar with the social distinctions established within the Colony over the previous century and a half, all three would have recognised that being Christian, as well as promising other-worldly salvation, enhanced one’s status in this world.

There were many in the colony who were extremely suspicious of Kicherer’s missionary work, with its emphasis on salvation and education – a view that reasserted itself when the Cape returned to Dutch control in 1803. Martin Hinrich Lichtenstein was a young German doctor and naturalist who arrived at the Cape with General Janssens, the governor appointed by the the Batavian Republic.

Kicherer's Missionary Institute at the Sack-rivers gate

published in Hinrich Lichtenstein’s 1812 Travels in Southern Africa in the Years, 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806

In mid-1805 Lichtenstein was sent to investigate the conditions in Bushmanland and visited Kicherer’s mission at Zak river, of which he noted ‘so much boasting has been made by himself and his friends in Europe’ – an image of the settlement was made for the English edition of Lichtenstein’s account.

Lichtenstein suggested that both Kicherer and Van der Kemp ‘seemed wholly to forget that mankind was destined to work as well as to pray’. In Kicherer’s absence those remaining at the mission had become dejected, and he claimed were generally ‘Bastard-Hottentots: several of them were entirely white; and the greater part had been baptised before they came hither; some were even born of christian parents’.

Lichtenstein went as far as to claim that Mary, Martha and John had been baptised at Cape Town by a preacher called Fleck long before they even met Kicherer. While acknowledging that people at the mission had been instructed in Christianity, Lichtenstein asserted that ‘the fact is, that they would have been much better employed in the service of the colonists, providing for their wants by industry, than pursuing, as they did here, lives wholly useless, and abandoned to sloth’.[23]

When Kicherer arrived back at the Cape in early 1805, Governor Janssens proclaimed a new policy: missions could be established beyond the boundaries of the colony, but must have no communication with its inhabitants, who were prohibited from attending missionary schools. Missionaries were specifically prohibited from recruiting anyone from the service of their masters – no one working for a colonist or who had worked for a colonist in the past year could join a mission.

With the boundaries of the colony redrawn to include both Kicherer and Van der Kemp’s missions, it was declared that these could remain, but were prohibited from teaching writing. Instead they were encouraged to concentrate on training people to cultivate the land. Finally, missionary settlements were only allowed to offer prayers for the Batavian Republic and the Cape Colony.

Returning to the Zak River in October 1805 Kicherer found the river had dried up and the mission’s main supporter among the farmers, Floris Visser, had died. A San raid carried off 200 sheep the following month, prompting the newly married Kicherer to conclude that he was, after all, called to become a Government appointed minister in the colonial town of Graaff-Reinet.

In 1806, less than three years after Mary, John and Martha visited London, and just as the British resumed their control of the Cape, the Zak River Mission was abandoned.

Reinet House, the Old Pastor

now a Museum, built as a parsonage for Kicherer by the Cape government, using the labour of enslaved people

[1] Jensz, Felicity, and Hanna Acke. “The Form and Function of Nineteenth-Century Missionary Periodicals: Introduction.” Church History 82, no. 2 (2013): 368-73. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0009640713000036.

[2] Sivasundaram, Sujit. Nature and the Godly Empire : Science and Evangelical Mission in the Pacific, 1795-1850.Cambridge Social and Cultural Histories ; 7. Cambridge ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005, 105-110.

[3] Elbourne, Elizabeth. Blood Ground : Colonialism, Missions, and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799-1853. Mcgill-Queen’s Studies in the History of Religion. Series Two ; 19. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002, 126.

[4] http://www.ephemera-society.org.uk/items/2012/apr12.html

[5] Evangelical Magazine 1804, p.517

[6] Transactions Volume 2, v-vii

[7] The Converted Hottentots. Vol. The Cottage Library of Christian Knowledge, a new series of religious tracts. London, 1804, 2.

[8] Transactions Volume 1, iv

[9] Transactions Volume 1, xvi

[10] Transactions Volume 1, 325; Missionary Magazine, 21 Octiber 1799, 477

[11] Transactions Volume 1, 369

[12] Barrow, John. An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa in the Years 1798 and 1798. T. Cadell & W. Davies, 1801, 85.

[13] Transactions Volume 1, 326

[14] Transactions Volume 1, 329

[15] Transactions Volume 1, 336

[16] Transactions Volume 1, 331

[17] Transactions Volume 1, 337

[18] Elbourne, Elizabeth. Blood Ground : Colonialism, Missions, and the Contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799-1853. Mcgill-Queen’s Studies in the History of Religion. Series Two ; 19. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002.

[19] Transactions Volume 2, 9

[20] Transactions Volume 2, 6-7

[21] Transactions Volume 2, 3

[22] Evangelical Magazine 1804, p.547

[23] Lichtenstein, H. Travels in Southern Africa in the Years 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806. Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society (1928), 1812, 183-6.

0 Comments