Introduction

When anthropologists come to examine the role of Christian missionaries in the transformation of non-Western societies… they soon become deeply embroiled in debates about narrative.

Peel, J. D. Y. (1995). For Who Hath Despised the Day of Small Things? Missionary Narratives and Historical Anthropology. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 37(3), 581-607. doi:10.1017/S0010417500019824

If we are prepared to see artefacts as the enactment of events, as memorials of and celebrations to past and future contributions – if the axe blade really is an icon of exchange relationship – then we must be prepared to switch the metaphors the other way too – to empty our notion of history as the natural or chancy occurrence of events that present a problem for structure…

Strathern, Marilyn (1990). Artifacts of history: Events and the interpretation of images, in Culture and history in the Pacific, edited by Jukka Siikala (Helsinki), 25–44.

In 1922, a hundred years ago this year, Bronislaw Malinowksi published Argonauts of the Western Pacific, his account of Kula voyages off the eastern tip of New Guinea. During these voyages, participants aimed to acquire Kula valuables through ceremonial exchange – necklaces of red spondylus shell, called soulava, and bracelets of white shell, called mwali. By acquiring, holding and subsequently exchanging these goods, certain men were able to advance and enhance their status.

Malinowski’s book has come to be seen as the archetypal ethnographic text, inaugurating what has been called ‘the phase of modernism in English-speaking anthropology’ (Ardener 1985; Strathern 1990, 1987). One way of understanding the title of Malinowksi’s book is to regard the islanders as early twentieth-century equivalents of the sailors who crewed the Argo of Ancient Greek myth, a ship captained by Jason and protected by the Gods. But Argonauts was not the only book published in 1922 to adopt a classicising title – James Joyce’s Ulysses – a central text in the canon of literary modernism – transposed the voyages and adventures of Odysseus, chronicled in Homer’s Odyssey, onto an ordinary day in Dublin, with Leopold Bloom as its hero.

Modernism as an aesthetic and literary movement was consolidated in the years after the First World War – a period in which the world was essentially remade – after around 750 years as a centre of English power, Dublin became the capital of the independent Irish Free State in 1922. Old ideas and established authorities were challenged as a new generation of men, Malinowksi and Joyce among them, asserted themselves. If the Argonauts were the Kiriwinans of the Kula ring, then it seems that like Leopold Bloom in Ulysses, Malinowski was the modern(ist) Jason – the legendary hero tasked with bringing back the golden fleece.

Argonauts of the Western Pacific by Bronislaw Malinowski, originally published in 1922

It helps here to know that one of the major works of anthropology before the First World War was The Golden Bough by James Frazer, originally published in two volumes in 1890, three volumes in 1900 and an incredible twelve volumes in the third edition between 1906 and 1915. Frazer’s comparative compendium of mythology developed in relation to the Rex Nemorensis, the priest-king of the sacred grove on the shores of Lake Nemi in Italy.

In order to become the priest-king, one had to kill the existing priest in combat, after taking the golden bough from one of the trees in the sacred grove. Frazer suggested that the institution of the death and reinstallation of the priest-king was an embodiment of the dying and reviving solar god, central to mythological ideas all over the world – including the death and resurrection of Jesus.

Malinowski himself had been inspired to become an anthropologist by reading the Golden Bough in three volumes, borrowed from the University of Cracow library:

I realised then that anthropology, as presented by Sir James Frazer, is a great science, worthy of as much devotion as any of her elder and more exact sister studies and I became bound to the service of Frazerian anthropology.

(Gellner 1987, 51)

The Golden Bough by James Frazer, published in 12 volumes between 1905 and 1915

If Frazer was the reigning priest-king of early twentieth-century British Anthropology, Malinowski’s publication of Argonauts can be read as him presenting his own golden bough. In asking James Frazer to write book’s preface, Malinowski was essentially asking for the inauguration of his own reign – like Jason claiming his rightful place as king following presentation of the golden fleece. Malinowski is remembered for developing the notion of the charter myth, and he certainly deployed the myth of his fieldwork in the Trobriands as a charter from which to establish Social Anthropology as a new approach.

The Golden Bough was also a significant influence on Joyce (as well as T.S. Eliot, who published The Waste Land in 1922), as well as other modernists such as Joseph Conrad. Indeed, Malinowski admired Conrad, a fellow Pole, telling Brenda Seligman that ‘Rivers is the Rider Haggard of Anthropology, I shall be his Conrad!’ (Young 2004, 236). By aligning W.H.R. Rivers (who died in 1922) with Rider Haggard, Malinowski was suggesting he exemplified an imperial tradition of British writing about the non-European ‘other’ which he hoped to overturn in the way Conrad’s Heart of Darkness had upended romantic Imperial narratives into a denunciation of colonialism, highlighting the ways it dehumanised the Europeans who participated in it.

Although Malinowski presented his work as inaugurating something of a revolution in Anthropology, his approach was significantly shaped by his engagement with Frazer, providing at the very least an explanation for the title of his book. In the same way that Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is structured around the story of a European’s voyage to the interior of the African continent, where he comes to dominate and rule, Malinowski’s account, while ostensibly about the Kula, also emphasises his own heroic role as an ethnographer who gains an understanding of the operation of Kula that is essentially superior to that of those who participate in it. This is an anthropological version of ‘the hero’s journey’ myth – explored by Joseph Campbell’s 1949 book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces (a major influence on George Lucas’ Star Wars franchise and not unrelated to what Teju Cole called ‘the White-Saviour Industrial complex’ in 2012).

Ulysses by James Joyce, first edition published in 1922

Across the literary and artistic manifestations of modernism, a common theme is the European appropriation and of ‘the primitive’ in order to refresh or renew the artistic and intellectual traditions of Europe. It was not uncommon for mid-century Europeans to see themselves as the ones who ‘really’ understood artistic or ceremonial practices in other parts of world. Although twentieth-century Social Anthropology has been recognised as a modernist form of Writing Culture (Clifford and Marcus 1986), the fact is that Argonauts of the Western Pacific is still widely regarded as an exemplary ethnographic text.

Indeed, Malinowski’s description of romantically isolated fieldwork remains the standard against which many doctoral anthropology students measure their own efforts, suggesting it has been hard for the discipline to escape the dominating and perhaps domineering influence of the modernists, whose charter myths continue to position them as founding ancestors, or priest-kings in the cult of Social Anthropology.

For all Malinowksi’s iconoclastic ambitions, the narrative structure of his account betrays a continuity with older European accounts of encounter with other parts of the world. It is striking that central targets for the Modernist generation, from which they sought to distance themselves, perhaps as a result of the what Freud in 1917 called the ‘narcissism of small differences’, were missionaries, but also the museum collections – assembled in anthropological museums during the previous thirty years.

Modernist anthropologists railed against what they represented as ‘conjectural history’ – the efforts of those who attempted to build frameworks for human history extending beyond the European old world on the basis of facts and artefacts assembled in Europe – an approach increasingly derided as ‘armchair anthropology’. Modernism, and anthropological modernism in particular, was unrelentingly presentist (Fardon 2005). The aim was to explain the operation of society by reference to its contemporary features and characteristics, in the way an anatomist might explain the function of different organs of the body without reference to their evolutionary history.

Bronislaw Malinowski in his tent in the Trobriands

Malinowski's tent on the beach in the Trobriands

But Malinowski did not swim to the Trobriand Islands. His access to the field, like that of many anthropologists of his generation was made substantially possible by established networks of Christian missionaries who had operated in Africa and the Pacific for over a century. In the case of the Trobriands, the Methodist missionary M.K. Gilmour had been stationed at Kiriwina for 14 years when Malinowski arrived in 1915 (Young 1984, 17). Many of Malinowski’s immediate predecessors, the first generation of professional anthropologists, found employment in museums that were filled by collections of material assembled in Europe largely through the efforts of previous generations of missionaries.

In the Right to Look- a counterhistory of visuality, Nicholas Mirzoeff (2011) has suggested that the missionary can be regarded as the metonymic figure of what he called the ‘Imperial Complex of Visuality’, dominant between 1860 and 1945 – as heroes who brought ‘Light into Darkness’ as part of a global “pastorate”. This draws on Michel Foucault’s insight that many of the technologies of governmentality of the modern state were assimilated from forms of Christian pastoral power (Goulder 2007). Thus an enquiry into missionary practice and image making has the potential to illuminate what Talal Asad (2003) has called Formations of the Secular.

Historians such as Boyd Hilton (1988) have demonstrated the significant influence that the 18th century evangelical revival had on British intellectual and cultural forms during the nineteenth century. I would go as far as to suggest that the public museums that took shape in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, as part of what Tony Bennett (1988) has called the ‘exhibitionary complex’, can be regarded as an expansion of the ‘missionary exhibitionary complex’ that developed in evangelical circles earlier in the century. My intention in presenting chronologically ordered chapters is to provide a more detailed insight into the development of these related exhibitionary complexes.

However, I remain conscious of the textual form I am creating – it would easy to describe a narrative arc from origin, through rise, to decline and fall. But would this simply be an appealing way to shape a story out of the messy details of historical events and sources? A Foucauldian genealogy might trace relationships of descent and alliance, but my intention here is less to construct a genealogy than to provide a gallery of ancestral portraits, which the reader/viewer is encouraged to explore in order to recognise and identify family resemblances.

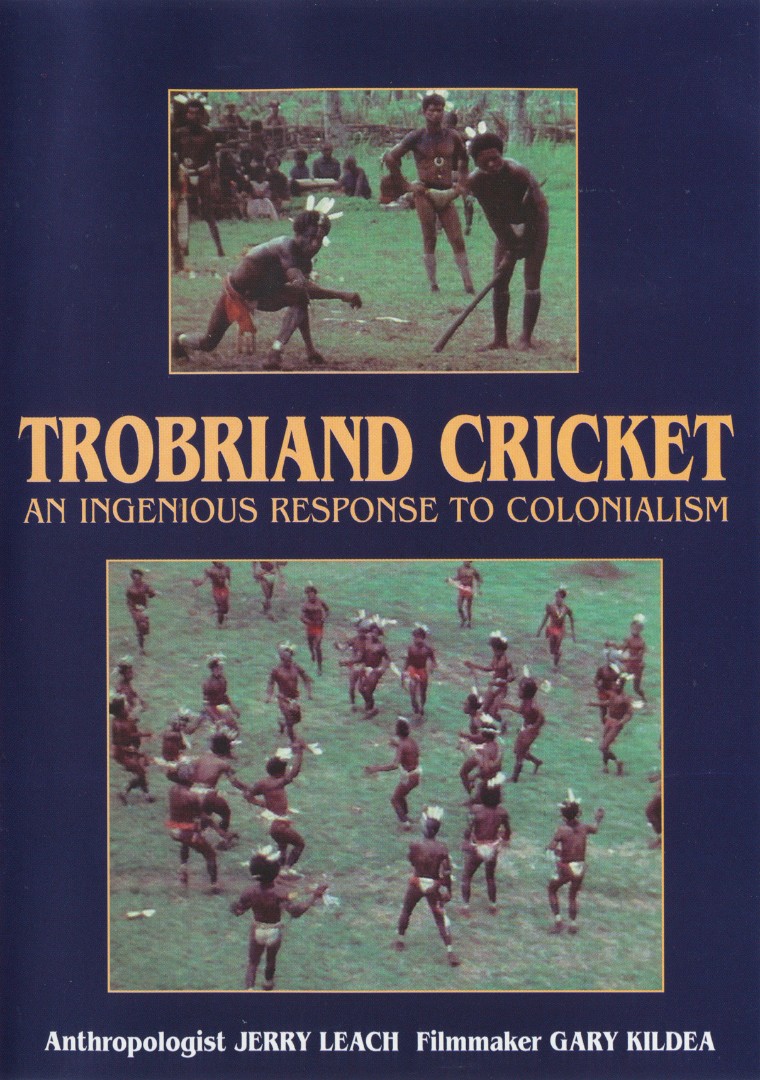

Trobriand Cricket (cover for 1973 film): the missionary Gilmour is remembered for introducting the game as a substitute for warfare

Marilyn Strathern (1990) has described the typical approach of modernist anthropology to both artefacts and events as one that makes sense of them in relation to a context. She has contrasted this with what she has called a Melanesian approach to images, whether events or artefacts, as embodying history themselves – they do not need to be “explained” by reference to events outside themselves, but are known by their effects. An image or artefact, when approached as a prestation (or gift) demands reciprocation, so that it comes to be understood through the construction of further artefacts in order to see what their further effects will be, with revelations coming as something of a surprise.

I would collapse Strathern’s dichotomy between the Melanesian and European approaches (which is itself essentially Modernist) by suggesting that the texts constructed to make sense of things by “Europeans”, by which she essentially means modernist anthropologists (Strathern recognises that museum curators are more like “Melanesians” than her “Europeans”) are artefacts themselves, containing their own contexts. In a world in which the British Library is a distinct institution from the British Museum, we might think of texts as unlike other artefacts, but it is in fact not long since they were part of a single institution (1973). Indeed, most libraries contain artefacts that could happily form part of a museum collection, and vice versa.

One can read Malinowski’s text as an artefact of a particular type, constructed to evoke a context for the Kula that will allow himself and other Europeans to make sense of it. But typically, the institutions of human life do not come with such manuals. One joins the game of life in the midst of play, and learns the rules by watching and then joining in. In Roy Wagner’s (1981) terms, Malinowski, as the ethnographer, “invents” the culture of the Trobriands through the construction of his text(s). Strathern suggests that as part of the modernist approach to Anthropology “it is taken for granted that we study the significance which such artefacts have for the people who make them, and thus their interpretations of them”, but if these assumptions were at least identifiable by 1990, I suggest they should no longer be taken for granted in 2022.

A hundred years after the publication of Malinowksi’s Argonauts, I am seeking to revisit the moment of possibility represented by 1922, a return to what Michael North (1999) has called the ‘scene of the modern’. While the COVID19 pandemic has been very different to the First World War, it nevertheless provides a break from business as usual that makes it possible to consider alternative ways of approaching things.

How best can one write about human life in a way that resists the urge to endlessly contextualise – a tendency to lapse into an essentially theological mode of writing that attempts to elucidate what Malinowski liked to call ‘the native’s point of view’? Who are /were ‘the natives’ in encounters between missionaries and the people they worked with, and did they really have a single point of view? Is it possible to capture the contingency, uncertainty and provisional nature of much of human life by constructing our accounts differently?

David Graeber and David Wengrow (2021; 5, 24) have recently challenged us to write history ‘as if it consisted of people one would have been able to talk to, when they were still alive’ as part of an attempt to construct a new science of history that ‘restores our ancestors to their full humanity’. It is to this challenge that I have attempted to respond.

Soulava kula valuable, collected by Bronislaw Malinowski in the Trobriand Islands

In his work on the encounters between missionaries and the Yoruba, in what is now Nigeria, J.D.Y. Peel (1995; 2000) drew attention to the centrality of narratives, both in terms of how they structure historical accounts, but also the way in which they were used by participants in these encounters to make sense of their own experiences.

In response to the work of the Comaroffs (1991, 1997), whose work concentrated on the connections between missionary encounters and the expansion of global capitalism, Peel has suggested that accounts of missionary encounters that do not recognise the centrality of religious narratives runs the risk of reading like Hamlet without the Prince of Denmark.

World religions like Christianity, Peel (1995, 9) suggests, are long durée ‘vehicles of trans-historical memory, ceaselessly re-activated in the consciousness of their adherents’. Those engaged in missionary encounters frequently compared and judged their own actions on the basis of biblical precedent, drawing on the complex strands of both the Old and New Testaments to make sense of their own encounters.

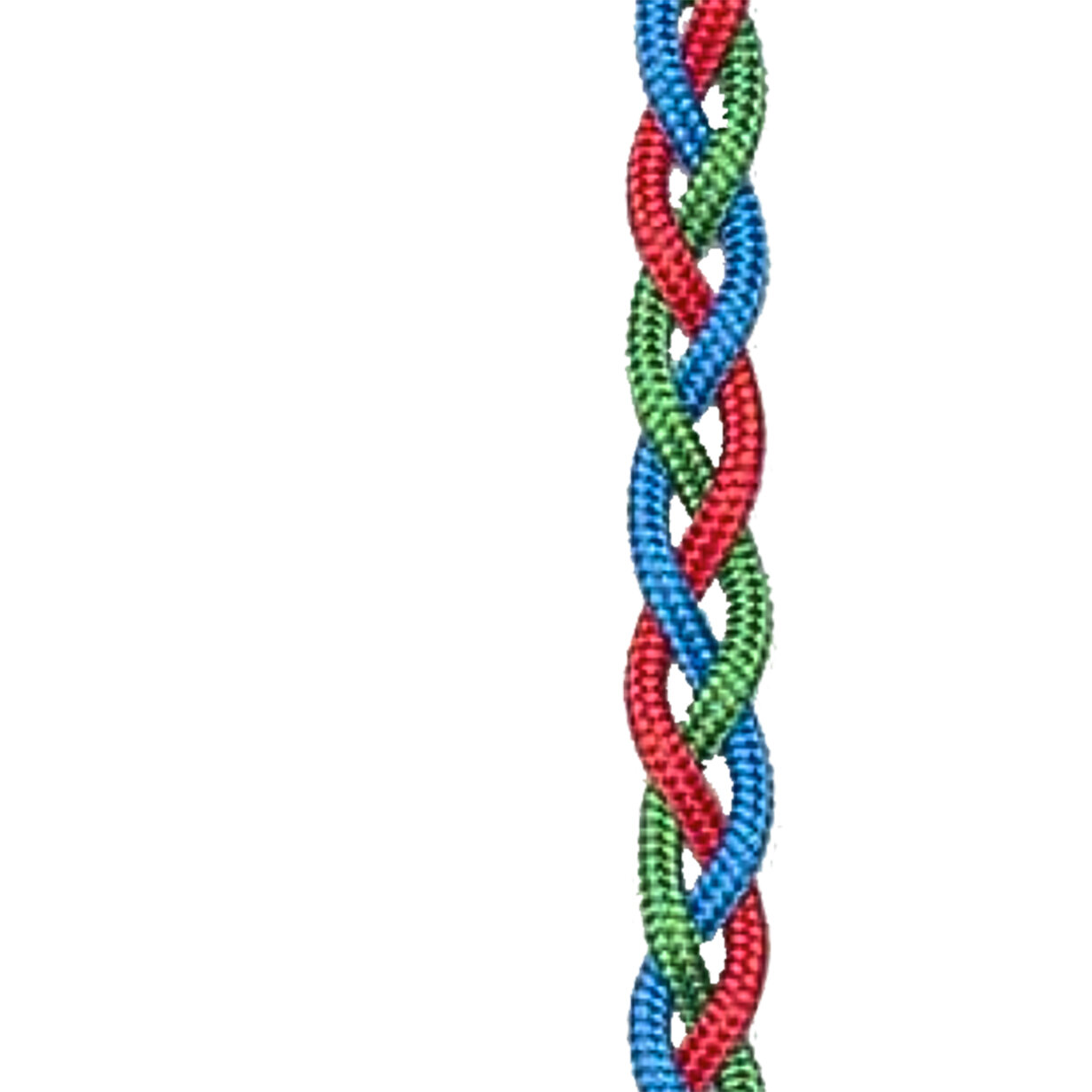

In constructing his own account, Peel worried about ‘how to simplify a complicated and many-stranded story without distorting its essential elements’ (Peel 2000, 44), ultimately arriving at a material metaphor:

A multi-coloured wooden cord, with component fibres of different lengths – Yoruba, colonial, Christian, and other – that give it structure by pulling both together and against one another.

It is striking that in setting out his vision of the history of human thought, Frazer constructed a similar material metaphor:

A web of three different threads – the black thread of magic, the red thread of religion, and the white thread of science, if under science we may include those simple truths drawn from the observation of nature…

Could we survey the web of thought from the beginning, we should probably perceive it to be at first a chequer of black and white… But carry your eye further along the fabric and you will remark that, while the black thread and white chequer still run through it, there rests on the middle portion of the web, where religion has entered most deeply into its texture, a dark crimson stain…

(Frazer 1911, 307-8)

In constructing an artefactual history of the London Missionary Society, my ambition is to construct a narrative out of multiple interlocking strands, that come in and out of conjunction with one another in different ways at different times.

Three stranded cord

Textual models range from nineteenth century novels such as George Elliot’s Middlemarch and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick to more recent works such as David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, or even Deleuze and Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus. But in the deeper past we might consider the multi-stranded text of Herodotus’ Histories, or even the Bible itself. In attempting to go beyond what Ann-Laura Stoler (2009) has called ‘familiar stories with predictable plots’, we have a range of textual artefacts to consider as models that do not conform to modernist monomyths – a significant example drawn from twentieth century anthropology would be Gregory Bateson’s (1936) Naven.

I am not advocating a straightforwardly neo-Frazerian approach, but I do feel that it may be revealing to consider missionary encounters, as well as the way they have been narrated, in light of the archetypical story of the priest-king at Nemi. Indeed, I am tempted to regard many of the artefacts collected and brought to Europe as essentially equivalent to Trobriand Kula valuables, but also to the Golden Fleece which Jason returned with to prove his right to rule.

The widespread adoption of Christianity in large parts of the world over the past two centuries, including Africa and the Pacific in particular, is a transformation of world-historical significance that cannot be accounted for simply by the imposition of European power, or the cultural logic of capitalism – many missionaries were essentially powerless strangers, at least at the point they arrived.

I take further inspiration from Chinua Achebe’s 1958 Things Fall Apart – an African response to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness – which recognises the tensions inherent in existing structures of power, and the forms of possibility that the arrival of outsiders missionaries presented for many people. The stranger missionaries did not become priest-kings entirely by their own efforts.

If the functionalist anthropology of the Modernists concerned itself with how society maintains itself as a functioning system in a steady state or dynamic equilibrium, giving rise to a conception of culture as essentially inherited and determinative, then in a world structured around forms of managerialism intent on maintaining an unsustainable status quo, it has become increasingly urgent to find ways of writing about the mechanisms of societal transformation. How does society renew itself? How does newness enter the world (Bhabha 1994)?

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe - cover for first edition, published in 1958

Ardener, Edwin. 1985. Social Anthropology and the Decline of Modernism. In Reason and Morality, edited by J. Overing. London: Tavistock Publications.

Asad, Talal. 2003. Formations of the Secular: Christianity, Island, Modernity: Stanford University Press.

Bateson, Gregory. 1936. Naven : a survey of the problems suggested by a composite picture of the culture of a New Guinea tribe drawn from three points of view. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bennett, Tony. 1988. The Exhibitionary Complex. new formations 4 (1):73-102.

Bhabha, Homi K. 1994. The location of culture. London: Routledge.

Clifford, James, and George E. Marcus. 1986. Writing culture : the poetics and politics of ethnography. Berkeley ; London: University of California Press.

Comaroff, Jean, and John L. Comaroff. 1991. Of revelation and revolution : Christianity, colonialism, and consciousness in South Africa. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press.

Comaroff, Jean, and John L. Comaroff. 1997. Of revelation and revolution : The Dialectics of Modernity on a South African Frontier. Chicago ; London: University of Chicago Press.

Fardon, Richard. 2005. Tiger in an Africa Palace. In The Qualities of Time: Anthropological Approaches, edited by W. James and D. Mills. Oxford: Berg.

Frazer, James George. 1911. The golden bough : a study in comparative religion. London: Macmillan.

Gellner, Ernest. 1987. Culture, Identity, and Politics: Cambridge University Press.

Goulder, Ben. 2007. Foucault and the Genealogy of Pastoral Power. Radical Philosophy Review 10 (2):157-176.

Graeber, David and David Wengrow. 2021. The Dawn of Everything; A New History of Humanity. London ; Penguin Random House.

Hilton, Boyd. 1988. The age of atonement : the influence of evangelicalism on social and economic thought, 1795-1865. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Mirzoeff, Nicholas. 2011. The Right to Look: A Counterhistory of Visuality: Duke University Press.

North, Michael. 1999. Reading 1922: A Return to the Scene of the Modern: Oxford University Press.

Peel, J. D. Y. 1995. For Who Hath Despised the Day of Small Things? Missionary Narratives and Historical Anthropology. Comparative Studies in Society and History 37 (3):581-607.

Peel, J.D.Y. 2000. Religious Encounter and the Making of the Yoruba: Indiana University Press.

Stoler, Ann Laura. 2009. Along the archival grain: epistemic anxieties and colonial common sense. Princeton, N.J. ; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Strathern, Marilyn. 1987. Out of Context: The Persuasive Fictions of Anthropology. Current Anthropology28:251-281.

Strathern, Marilyn. 1990. Artefacts of History: Events and the Interpretation of Images. In Culture and History in the Pacific, edited by J. Siikala. Helsinki: The Finnish Anthropological Society.

Wagner, Roy. 1981. The invention of culture. Rev. and expanded ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Young, Michael W. 2004. Malinowski: Odyssey of an Anthropologist, 1884-1920: Yale University Press.