Shot in the Griqua Country, South Africa, by Campbell’s Party

Klaarwater, 31 July 1814

The title of this chapter comes from a Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, printed in 1826 and preserved in the British Library. The museum opened in 1815 and a visitor in 1819 recalled a ‘very fine cameleopard’, suggesting the giraffe was a feature of the museum from its earliest days.1

Images of the museum from the 1840s and 1850s, such as that above, have the giraffe at their centre, its head reaching into the space of an overhead skylight. An immobile spectre, this towering creature dominated the museum across three locations and nearly fifty years.

But how did it come to occupy this imposing position, and who was ultimately responsible for its killing, preservation and transportation to Europe?

On 24 June 1812, the Rev. John Campbell, a forty-six-year-old Congregational Minister from Scotland, boarded the Isabella convict transport ship at Gravesend in Kent, bound for Africa.

Formerly an ironmonger in Edinburgh, Campbell had been interested in Africa for decades – he had campaigned for the abolition of the slave trade, and was a friend of John Newton, the former slave trader who penned Amazing Grace.

Campbell had been the motivating force behind the Society for the Education of Africans, hoping that schooling in Britain might convert young Africans through Grace and the Gospel, enabling them to return and transform their home countries.

Leading Anglicans feared the impact of an Edinburgh education, resolving in 1799 that the 20 boys and 4 girls sent from Sierra Leone ‘should remain in safety from contamination with any heretical or socialistic ideals’, at an African Academy in Clapham, London.2

Ordained the minister of Kingsland Chapel in London in early 1804, Campbell met Martha, Mary and John, the South African visitors, shortly after they arrived with Rev. Kicherer [Chapter 2].

Although he had never been to the continent of Africa, Campbell had experience of preaching tours across the highlands and islands of Scotland, as well as the North of England.

Mr John Campbell, Kingsland

The New York Public Library Digital Collections. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5a9b8ba0-c541-012f-5c0d-58d385a7bc34

Campbell was asked to visit the Cape by the Directors of the Missionary Society, following the death of Johannes van der Kemp at the end of 1811. Van der Kemp had been in the process of preparing to launch a mission to Madagascar, where his very young formerly enslaved wife originally came from.

The missionaries’ advocacy for the indigenous Khoisan people of the Cape, and the attention they had drawn to their abusive treatment by local farmers, had come to a head, and the Cape government was in the process of launching a commission to investigate their charges.3

What is more, Hinrich Lichtenstein had just published the English translation of his Travels in Southern Africa between the years 1803 and 1806, which included extremely unflattering descriptions of both van der Kemp and his missionary settlement Bethelsdorp.

This reflected suspicion among the settlers of what they called Bedelaarsdorp (Beggar’s village), partly due to the reluctance of its residents to labour on local farms.

Lichtenstein ridiculed both Van der Kemp’s adoption of local forms of dress, such as leather sandals, and questioned the marriages of both Van der Kemp and his fellow Bethelsdorp missionary, James Read, to extremely young non-white women.4

Campbell was tasked with visiting the mission stations in Africa to investigate. He was also asked:

… to establish such regulations… as might be most conducive to the attainment of the great end proposed – the conversion of the heathen, keeping in view at the same time the promotion of their civilization.5

Arriving at Cape Town after four months at sea, Campbell met friends including Kicherer, who had been minister of the Dutch Reformed Church at Graaf-Reinet since his return to South Africa. The Cape Colony had returned to British control in 1806 following a naval invasion during the Napoleonic wars, so Britain’s 1807 Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade applied there, at least in theory. Slavery, but also the trade in enslaved people, continued to operate however, and Campbell witnessed domestic slavery first hand at the Cape.

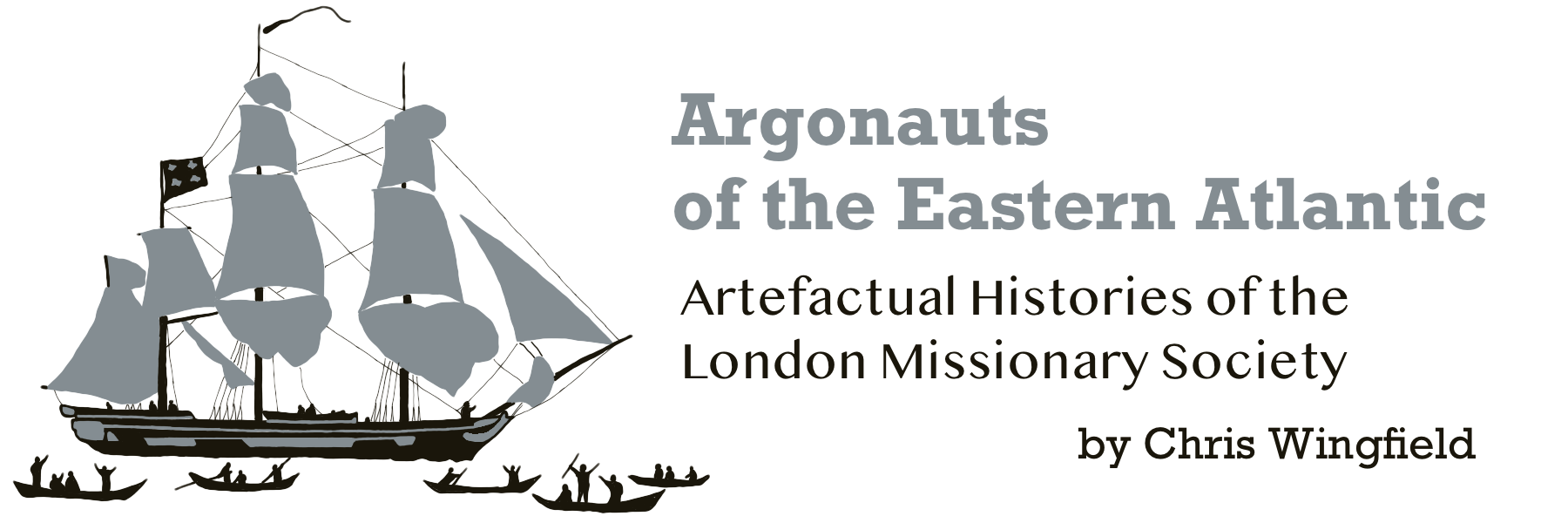

Household Utensils, Ornaments, and Weapons of the Beetjuans

published in Hinrich Lichtenstein’s 1812 Travels in Southern Africa in the Years 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806

The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1812. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-73ad-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

While he was at Cape Town, a ship carrying captives from Madagascar and Mozambique was seized and each captive was apprenticed to a Cape master for fourteen years, during which they were supposed to learn a trade, to read and the principles of Christianity. While decrying slavery as ‘a condition which shocks human nature’ and calling the prohibition on marriage by the enslaved ‘not only an act of great injustice… but a heinous sin against God’, Campbell felt that the ‘temporary captivity’ of apprentices might prove a blessing to their home countries, if they ever returned there.6

Interior of the Church at Genadendal

published in Christian Latrobe’s 1818 Journal of a visit to South Africa, in 1815, and 186.

Drawn by R. Cocking from original sketches by Christian Latrobe

https://historyarchive.org/works/books/journal-of-a-visit-to-south-africa-1818

Campbell’s first visits beyond Cape Town were to the Moravian missions of Groenekloef (now Mamre, established in 1808), and Genadendal (the place of Grace), South Africa’s earliest Christian mission. Established in 1738, it was abandoned for fifty years before being re-established in 1792.

Campbell visited the homes of the indigenous Khoekhoen families living at these missions, remarking on their cleanliness as well as their ‘mostly decent’ dress, while noticing that some still dressed in loose sheepskins.7 Echoing Lichtenstein’s description of the orderliness of these settlements, he nevertheless wrote down frightful stories about encounters with African animals, including a leopard attack.

It was not until mid-February 1813 that Campbell set off to inspect the Society’s own mission stations, going first to Bethelsdorp at Algoa Bay in the eastern Cape, Van der Kemp’s mission since 1803.

Travelling from Cape Town with two wagons, drawn by teams of twelve and fourteen oxen, Campbell was almost entirely reliant on the expertise and know-how of his Khoekhoen guides.

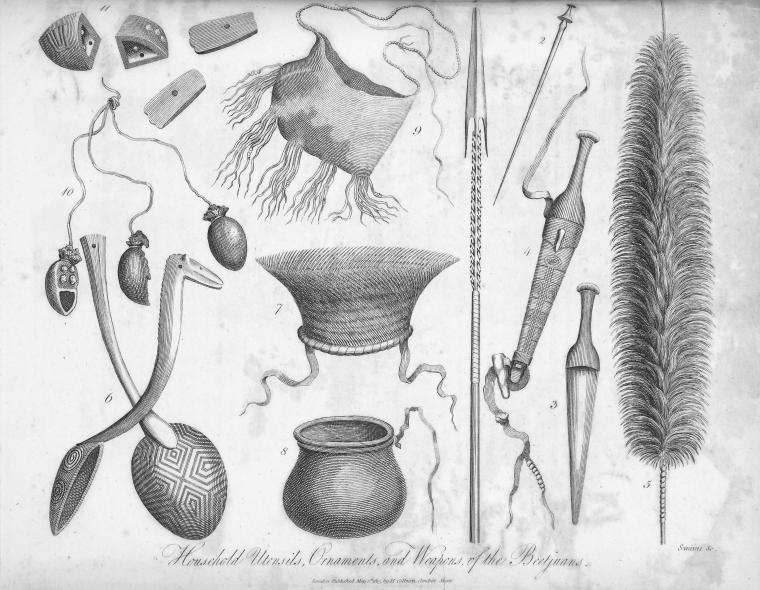

The party was overseen by Cupido Kakkerlak (Cupid Cockroach in Afrikaans), who Campbell called the group’s ‘travelling director’8, a Khoe preacher from Bethelsdorp who had been baptised by Van der Kemp in 1801.9

In addition ‘Britannia’, a Gonaqua man, drove the other wagon, while ‘John’ and ‘Michael’ led the oxen and ‘Elizabeth’ and ‘Sarah’ took care of cooking, washing, finding water as well as making regular coffees for the travelling party.

During the month long journey, Campbell formed an attachment to his companions, writing that they were:

far from being so barbarous a race as they are usually supposed to be by Europeans… They have nothing more savage about them than the peasants in England. I have seen families in London living in more dirty hovels than ever I saw Hottentots, and many in London have committed far more atrocious deeds than any I have ever heard the Hottentots charged with.

I think the Hottentot mind is better cultivated than the minds of many in the lower ranks in London; and I should expect to be much better served, and to be more safe in travelling with twenty Hottentots, than with twenty Europeans.10

The mission at Bethelsdorp was a rare place where Khoekhoen could live a fairly independent life within the colony, apart from when pressed to serve in the Cape Regiment – the majority of Khoekhoe not living at missions were forced to work as farm labourers. Vocational training seems to have been a strand at the mission, and William Corner, a Black missionary from Demerara, a Dutch colony in the Caribbean, had been training carpentry apprentices for around a year when Campbell arrived.

Cupido Kakkerlak

Stipple engraving by Thomas Blood

published by Williams & Son Stationers Court 1st Jan 1816

SOAS Council for World Mission Archive: https://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001571/00001

One of these was Jan Tzatzoe, son of a Xhosa chief of the amaNtinde lineage, who would go on to play a key role in the expansion of Christianity in South Africa. Tzatzoe presented Campbell with a wooden box he had made in the cabinet maker’s style ‘for containing any varieties I might happen to obtain higher up in Africa’.

Campbell was definitely not as impressed by the physical appearance of Bethelsdorp as he had been by Genadendal – he compared its irregularity to Norwich or Manchester – some houses having been abandoned. The lack of water supply also meant there weren’t any trees or gardens. He was equally unimpressed by the fact that many people still dressed in animal skins, but blamed Van der Kemp, suggesting he ‘seems to have judged it necessary, rather to imitate the savage in appearance, than to induce the savage to imitate him’! 12

Bethelsdorp

image published opposite p.70 in John Campbell’s 1815 Travels in South Africa

Scanned from the author’s personal collection

Visiting farms a mile and a half away, however, Campbell was impressed by the amount of cultivated land and when describing the Bethelsdorp cattle herd, stated that he had never seen so many beasts in one place apart from at Smithfield market in London.

Cupido, who had been born around 1760 grew up on a farm, and did his time as a farm labourer. However, he became a key figure among the founders of Betheldorp, when land had been allocated for the mission by Batavian authorities in 1803-4.

At Bethelsdorp, Cupido worked for himself as a sawyer and wood trader, while his wife made soap for sale. Together they built up a herd of ten oxen and purchased a wagon. The church became increasingly important in Cupido’s life, and he was one of the first people at the mission to learn to read and write.

While he thought there was still room for improvement, Campbell concluded that during its first decade Bethelsdorp had become a self-sustaining Christian community of around a thousand people, with over two thousand cattle. A significant measure of this, in Campbell’s eyes, was the money they raised to support the poor and sick, as well as missionary work elsewhere.

From Bethelsdorp, a party of five wagons set off in April 1813, intent on examining potential mission sites in Albany, recently cleared of its human inhabitants by a combination of Khoekhoen and British troops during the fourth frontier war of 1811-12. It was while travelling through this recently depopulated landscape that Campbell first encountered large African mammals such as elephants and buffaloes.

It was the thirty Khoekhoen in the party, however, including two who had originally been part of the Zak River mission [Chapter 2], who did all the hunting, at times mounted on oxen. They skinned and cut up animals to make biltong (preserved meat) and presented Campbell with various trophies, including the horns of the first buffalo they shot. Somewhere along the way, Campbell seems to have acquired his own sheepskin cloak or kaross, which he appreciated on cold nights.

Arriving at Graaf-Reinet at the end of April, Campbell met Kicherer, Martha, Mary and John, but also William Burchell, a young botanist and collector who travelled in the interior of South Africa between June 1811 and April 1815.

Klaas

Portrait of the man who accompanied French traveller Le Vaillant, wearing a sheepskin kaross.

published in 1790: Voyage de Monsieur Le Vaillant dans l’intérieur de l’Afrique par le Cap de Bonne-Espérance: dans les Années 1780, 81, 82, 83, 84 & 85, vol. 1, p. 212

The Interior of William Burchell's wagon

Painted from sketches by Burchell in February 1820 and exhibited at the Royal Academy later that year.

Writing to his mother, just before he set off from Cape Town, Burchell declared:

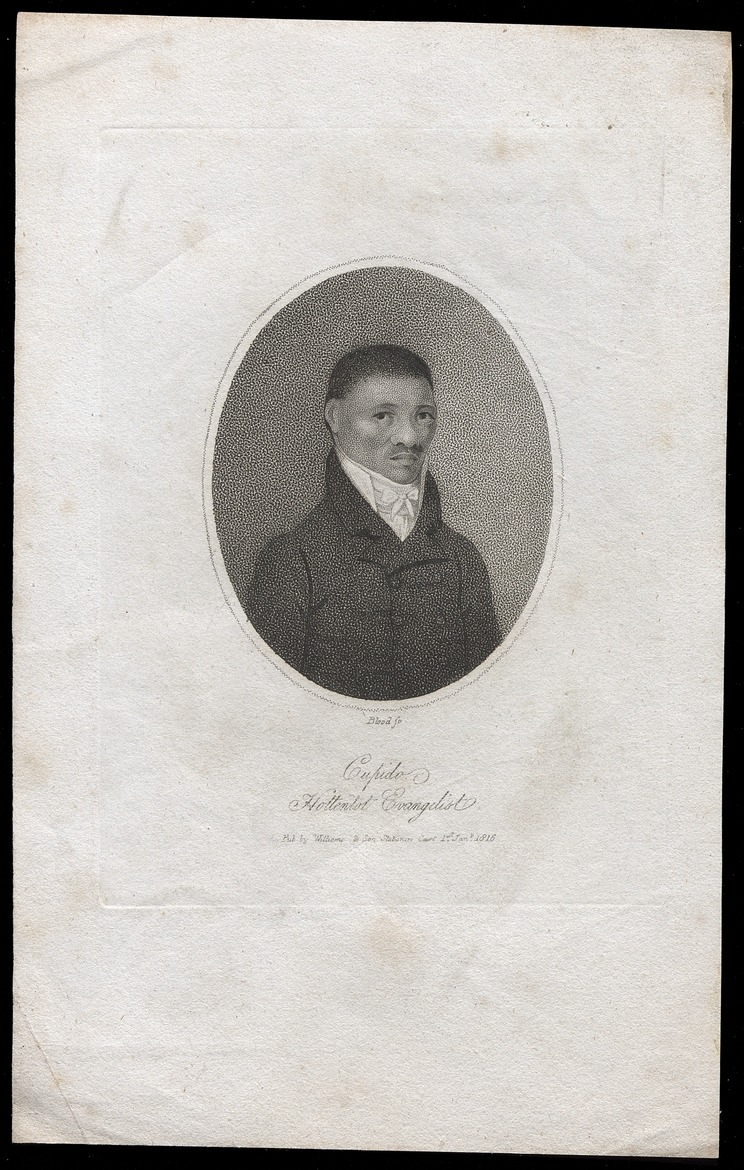

I do not consider myself out of the way of making money, when I think of the value of what I shall be able to obtain in my journey. I have been informed that a skin of the Camelopard which was shot in that country where I am going to, was sold in England for fifteen hundred pounds and though I cannot hope that if I bring one home it will sell for half that sum, yet should I be so fortunate as to discover the Unicorn, which has been supposed to exist in this part of Africa, I have not the least doubt of making five times that sum.13

Discussed in the same breath as the unicorn, the giraffe had until recently been considered a quasi-mythical beast in Europe, known from Classical texts that described it as camel-like with the skin markings of a leopard – hence camel-leopard.

The first skin and skeleton to arrive in England had been collected at the Cape in the late 1770s by William Paterson, another Scotsman, and was presented by his patron Lady Strathmore to John Hunter, whose anatomy collections became the Hunterian Museum at London’s Royal College of Surgeons.14

At around the same time Robert Jacob Gordon, a Dutch born soldier from the Scotch brigade, sent a giraffe skin to Holland, and a few years later the French traveller François Le Vaillant sent another to Paris that ended up in the Natural History Museum in Paris.

Burchell had initially travelled into the interior from Cape Town with missionaries, using the Society’s stations as the stopping points on his journey. Like Campbell, he was dependent on Khoekhoen guides and key among them was Stoffel Speelman, recently discharged from the Cape Regiment.15

Like Cupido, Speelman took charge of the practical aspects of the journey, finding water for the cattle and doing most of the hunting – for food as well as Natural History collecting. Burchell trained his assistants to cut and remove skins in a way that would enable subsequent taxidermy. In a journal entry, Burchell stated that:

In order to encourage Speelman in being diligent to shoot birds for my collection I have promised him a rix dollar for every dozen skins I preserve: And to whoever shall bring down a camelopardalis, any thing of my bartering goods he may choose.16

Burchell and Speelman twice made the dangerous journey on the route they pioneered between Graaf Reinet and Klaarwater, across so-called ‘Bushmanland’, and Campbell intended to follow in their footsteps.

At Graaf-Reinet, Burchell advised Campbell, but also agreed that one of his party could join them as a guide. How much they discussed Natural History collecting is unclear, but Burchell’s wagons must have already been impressively full, since he collected a total of 63,000 items during his travels.17

Campbell’s party of three wagons and numerous livestock and dogs completed this journey in early June 1813 when they crossed what he called the ‘Great River’, later known as the Orange, and now mostly called the Gariep, a transliteration of the Khoe words Kai !Garib, meaning ‘great river’.

Campbell’s published account of the journey describes them entering what he called ‘Griqualand’, but at the time was no such thing. The people they were on their way to see called themselves ‘Bastaard Hottentoten’ or just plain ‘Bastaards’, in acknowledgement of their mixed ancestry.

During his visit, Campbell persuaded them to abandon this term on account of “the offensiveness of the word to an English or Dutch ear”, and to rename themselves Griqua, since the Khoekhoen group they were most descended from was the “Gurigriqua”.They also renamed Klaarwater (Clear Water), their main settlement, Griqua Town – now mostly known as Griekwastad.18

The settlement was dominated at the time by the Kok and Barends families, fugitives from the expanding Cape Colony, who prospered by trading and raiding across the frontier. The advantages that guns and horses gave them over other residents of the African interior were considerable.

A mission had been established at Kok’s kraal in 1802, but relocated along with the people to Klaarwater shortly afterwards. By 1813 Campbell recorded a population of around 1300 Griquas, with another 1300 Corannas (another mixed Khoekhoen group) under their protection.

John Hunter's giraffe (c. 1780)

Original watercolour painting held among the Hunterian drawings in the Library of the Royal College of Surgeons, London.

Stoffel Speelman

Portrait by William Burchell, published in his 1822 Travels in the Interior of southern Africa, opposite p.167

The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1800 – 1899. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-ce06-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Griquatown Missionary Settlement, beyond the Great River

published in John Campbell’s 1815 Missionary Travels but based on an unacknowledged drawing by William Burchell.

Hugh Solomon Pictorial Africana Collection http://hdl.handle.net/10019.2/4289

Campbell published an image of ‘Griquatown’ in his book, but this had considerably more artistic merit than most of the other images, such as that of Bethelsdorp above, which were based on his own generally perspective-less sketches. The image derived from a drawing made by none other than William Burchell, who had given it to William Anderson. Anderson was a missionary of the Society who had worked in the region since 1801.

Burchell was extremely surprised and somewhat upset when he finally arrived back in Cape Town in 1815 and found that the drawing had not only been sent to England, but that it had found its way into Campbell’s account as a print, with no acknowledgment of its original source.19 Another pair of drawings, made by Burchell at Klaarwater in December 1811, show a giraffe skin propped up on a wooden scaffold in the midst of houses at the settlement, presumably in the process of being preserved for Burchell’s collection.

Although Campbell first saw giraffes while approaching the Orange River in June 1813, it was only at the end of July, following his return from a visit to Tswana settlements further north, that his party successfully shot one near Griqua Town.20 While writing letters back to London, Campbell heard musket shots and was fetched by a messenger who told him that the hunters wanted him to see the giraffe before it died.

When he arrived, it had already collapsed, but Campbell was amazed by its height, suggesting that a high horse could have walked between its legs. Presented with the skin to take to England by the person who shot it, presumably inspired by Burchell’s keenness on acquiring a similar skin a year before, Campbell happily added it to his collection.

In the days that followed, Campbell was gratified when the newly constituted ‘Griqua’, having agreed to a code of laws, system of justice and his proposal they should adopt their own currency, decided to rename one of their satellite settlements Campbell in his honour.21

Following the Gariep downstream before travelling south through Namaqualand, Campbell’s party arrived back at Cape Town at the very end of 1813.

Meeting John Craddock, the Governor of the colony early in the new year, Campbell was granted additional land for a new mission in Albany which he optimistically named Theopolis, the city of God.22

Returning to Britain, Campbell arrived at Plymouth in May 1814, and immediately began speaking and preaching about his journey – the giraffe skin was sent to the London taxidermist Benjamin Leadbeater for preparation.

Early in 1815, Campbell published an account of his journey – the frontispiece of which shows its diminutive author sheltering from the African sun under an umbrella in a pose reminiscent of the contemporary ‘selfie’.

Griqua Town coins

Minted by the Directors of the London Missionary Society in January 1816

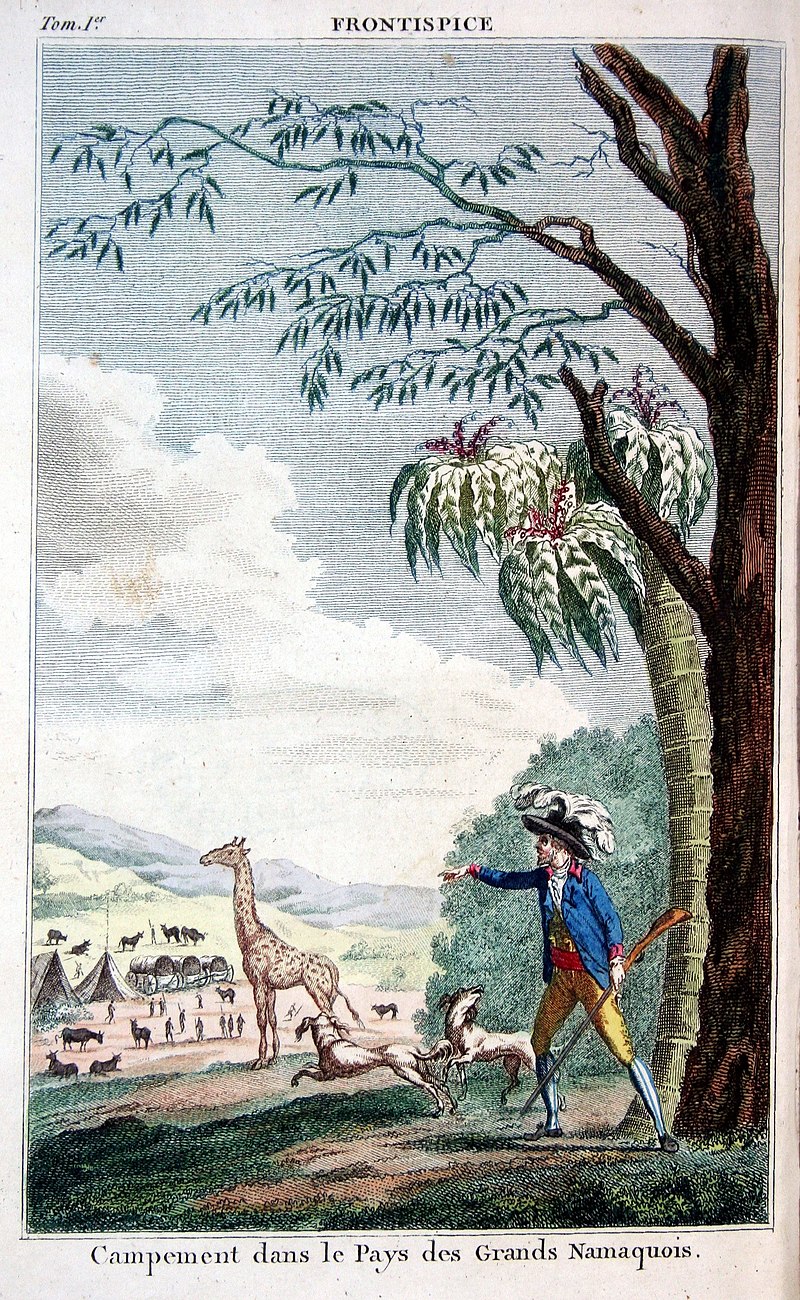

Frontispiece

by Henry Meyer, after William Thomas Strutt. Published in the John Campbell’s 1815 Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the Request of the Missionary Society.

Frontispiece

Published in Francois Le Vaillant’s 1790 Voyage de F. Le Vaillant dans l’intérieur de l’Afrique par le cap de Bonne Espérance, dans les années 1780-85.

The caption refers to the “waggons &c” pictured “on the Banks of the Great or Orange River”. While the landscape, and particularly the oxen, appear almost European, there is an element of the image that make it clear Campbell must be in Africa – the giraffe grazing on a tree in the background. This is an echo of the giraffe that Le Vaillant had himself depicted alongside for his own frontispiece a quarter century earlier.

Campbell’s return to London, accompanied all manner of trophies from his travels, not least the skin of a giraffe, appears to been the main reason why in the succeeding months the Missionary Society decided to take a set of nine rooms in the Old Jewry near Cheapside in the City of London, that included:

some for the reception of those curiosities which have been transmitted from Otaheite, China, South America, and particularly from South Africa. These will be prepared for public inspection as soon as possible.23

Bootchuanas Ornaments, Utensils & Weapons

Published in John Campbell’s 1815 Travels in South Africa

Scanned from the author’s personal collection

In June 1813, the Evangelical Magazine had been rebadged the Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle. Missionary news was published under a separate header at the back of the magazine and could be sent separately to Auxiliary Missionary Societies on a monthly basis.24

It was in the Missionary Chronicle for April 1815, shortly after the publication of Campbell’s book, that the opening of the Missionary Museum in London was announced. Members and friends of the society were invited to apply for a ticket to visit on Tuesday and Thursdays between 11am and 3pm from any of the Directors.

There, they would be able to gaze upwards at the towering giraffe, a decade before the first living giraffe made its way to the British Isles.25 A further note was added, soliciting further donations:

Ladies and gentlemen, possessed of any curious articles suited to this collection, and disposed to part with them, will greatly oblige the Society by presenting them to the Directors to enrich their Museum.

In April 1816 ‘idols of silver’ and copper arrived for the museum from Ballari in Karnataka, South India. In September, further ‘valuable curiosities’ from South Africa were announced.

These had been sent by Rev. Mr George Thom, who had travelled to South Africa with Campbell on his way to a missionary posting in Calcutta, but had been asked to remain in Cape Town as the Missionary Society’s agent. These items included:

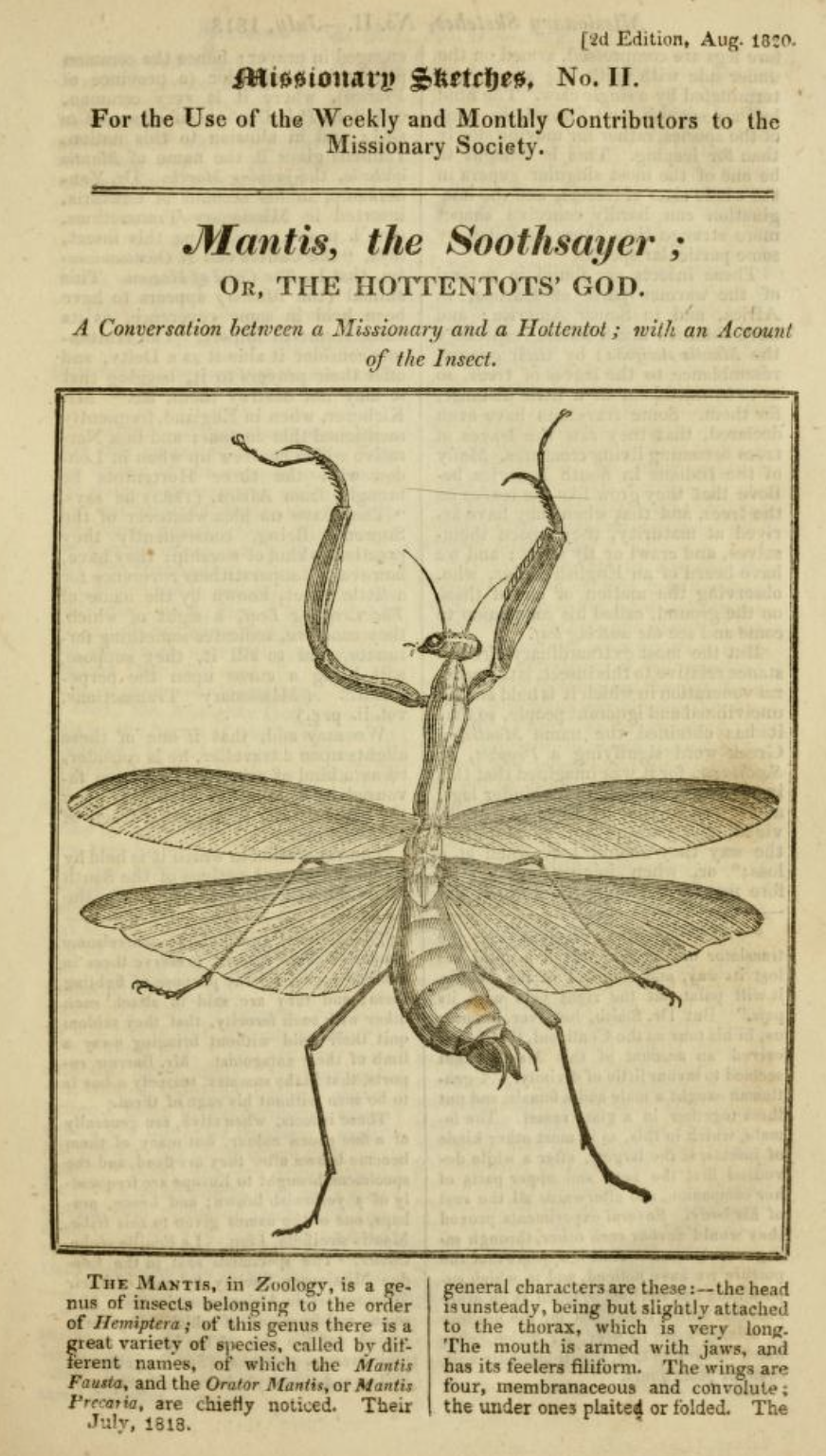

skins of a large lion, tyger, leopard, ant-eater, wild boar, lynx, goo, spring buck, kangaroo. & C.; together with various kinds of serpents – the puff-adder, the camelion and La Masité (commonly called The Hottentot’s God).

Though most of these items, like the giraffe, spoke more to South Africa’s natural history than to its religious state, the Afrikaans name for the praying mantis made it clear that the religious understandings of southern African people were not unrelated to the country’s wild creatures.

Soon afterwards ‘London’ was appended to the Missionary Society’s official name, partly to distinguish it from the Anglican Church Missionary Society, established in 1799. However, this choice of name also seems to have connected to the Society’s acquiring a physical headquarters with an attached museum in the city.

In September 1817, following his return to London, William Burchell presented 43 animals skins, including a pair of giraffes, not to the Missionary Museum but to the British Museum. Upset by the way in which the skins were subsequently neglected and allowed to decay, he complained and a number were eventually prepared for display.

Mantis, the Soothsayer

Published in Missionary Sketches 1820

Staircase of the old British Museum, 1845

Watercolur by George Scharf

By 1838 two of his giraffes were on display at the top of the British Museum’s staircase, alongside the smaller giraffe from the Hunterian collection, the first to reach Britain. An 1845 watercolour by George Scharf of the staircase at the British Museum features this trio of giraffes, accompanied by a diminutive rhinoceros.

While the skulls of the male and female giraffe presented to the British Museum by Burchell have survived, one bisected and the other with its horns sawn off, little else remains of the three giraffes shot and skinned near Klaarwater between October 1812 and July 1813.26

The 1826 catalogue of the Missionary Museum records that the giraffe was shot in Griqua country by Mr Campbell’s party, but also describes it in the following terms:

This very peculiar animal inhabits the interior parts of Africa, and the forests of Ethiopia. It is remarkable for the great disproportion of height between the fore and hind parts. The head is like that of a Stag; the neck is slender; the tail long, with strong hairs at the end; the whole is of a dirty white, marked with large broad rusty spots. It is very timid, but not swift; it runs awkwardly, and is easily taken. It browses on trees, yet can feed on the grass, and drinks water from the brook. Its height is from fifteen to seventeen feet, but some have been seen more than twenty feet. The specimen is about sixteen feet.

The Giraffe was known to the Romans in early times. It appears among the figures in the assemblage of eastern animals in the celebrated Praenestine Pavement, made by the direction of Sylla, and is represented both grazing and browsing, in its natural attitudes. It was exhibited at Rome by the popular Caesar, among other animals, in the Circasean Games.27

While classical knowledge of giraffes was recalled in this catalogue description, the detailed practical knowledge of hunters such as Stoffel Speelman and Cupido Kakkerlak, as well as their central role directing the journeys undertaken by both Campbell and Burchell, was essentially obscured from view when these giraffes were displayed in London.

Comments

This is an experiment in writing – that is intended to stretch the idea of the academic monograph.

I am keen to recognise and incorporate the input and expertise of others into the writing process, so adding comments here is one way to do this.

I would welcome any comments or feedback.

Notes

1 John Griscom, A year in Europe: comprising a journal of observations in England, Scotland, Ireland, France, Switzerland, the north of Italy, and Holland. In l8l8 and l8l9 (New York: Collins & Co., 1823), 239. http://books.google.com/books?id=RfcLAAAAYAAJ.

2 Bruce L. Mouser, “African academy—Clapham 1799–1806,” History of Education 33, no. 1 (2004), https://doi.org/10.1080/00467600410001648797.

3 Elizabeth Elbourne, Blood ground : colonialism, missions, and the contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799-1853, McGill-Queen’s studies in the history of religion. Series two ; 19, (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002).

4 H Lichtenstein, Travels in Southern Africa in the years 1803, 1804, 1805 and 1806 (Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society (1928), 1812), 235-40.

5 John Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society (London: Black and Parry, 1815), viii.

6 Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 4.

7 Khoekhoen litterally translates as ‘men of men’ but is used to describe the indigenous herding people of the cape, known at the time as ‘Hottentots’.

8 V. C. Malherbe, “The Life and Times of Cupido Kakkerlak,” The Journal of African History 20, no. 3 (2009): 369, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021853700017369.

9 V. C. Malherbe, “The Life and Times of Cupido Kakkerlak,” The Journal of African History 20, no. 3 (2009): 369, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021853700017369.

10 Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 65.

11 Roger S. Levine, A Living Man from Africa: Jan Tzatzoe, Xhose Chief, Missionary, and the Making of Ninteenth-Century South Africa (Yale University Press, 2011).; Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 84.

12 Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 95.

13 Letter dated 19 May 1811, Hope Library, Oxford University Museum

14 L.C. Rookmaaker, The Zoological Exploration of Southern Africa 1650 – 1790 (CRC Press, 1989), 176.

15 William John Burchell, Travels in the interior of southern Africa, vol. Voume 1 (London: Printed for Longman Hurst Rees Orme and Brown, 1822), 166.

16 Manuscript Journal, 24 May 1812 to 2 September 1812, Hope Library, Oxford University Museum.

17 Jane Pickering, “William J. Burchell’s South African mammal collection, 1810-1815,” Archives of Natural History 24, no. 3 (1997).

18 Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 252-3.

19 William John Burchell, Travels in the interior of southern Africa, vol. Volume 2 (London: Printed for Longman Hurst Rees Orme and Brown, 1824), 243.

20 Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 250.

21 Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 252-3.

22 Campbell, Travels in South Africa: Undertaken at the request of the Missionary Society, 352.

23 Missionary Chronicle for October 1814: 405: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IfADAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA405#v=snippet&q=rooms&f=false

24 {Brake, 2009 #3286@418}, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle, 21, 1818: 265

25 Evangelical: April 1815, p.171, ‘Missionary Museum’

26 Pickering, “William J. Burchell’s South African mammal collection, 1810-1815,” 320.

27 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars, (London: 1826), 15.

![JPG_Islandora_2923_Le Hottentot [graphic].](https://argonauts2022.net/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/JPG_Islandora_2923_Le-Hottentot-graphic..jpg)

0 Comments