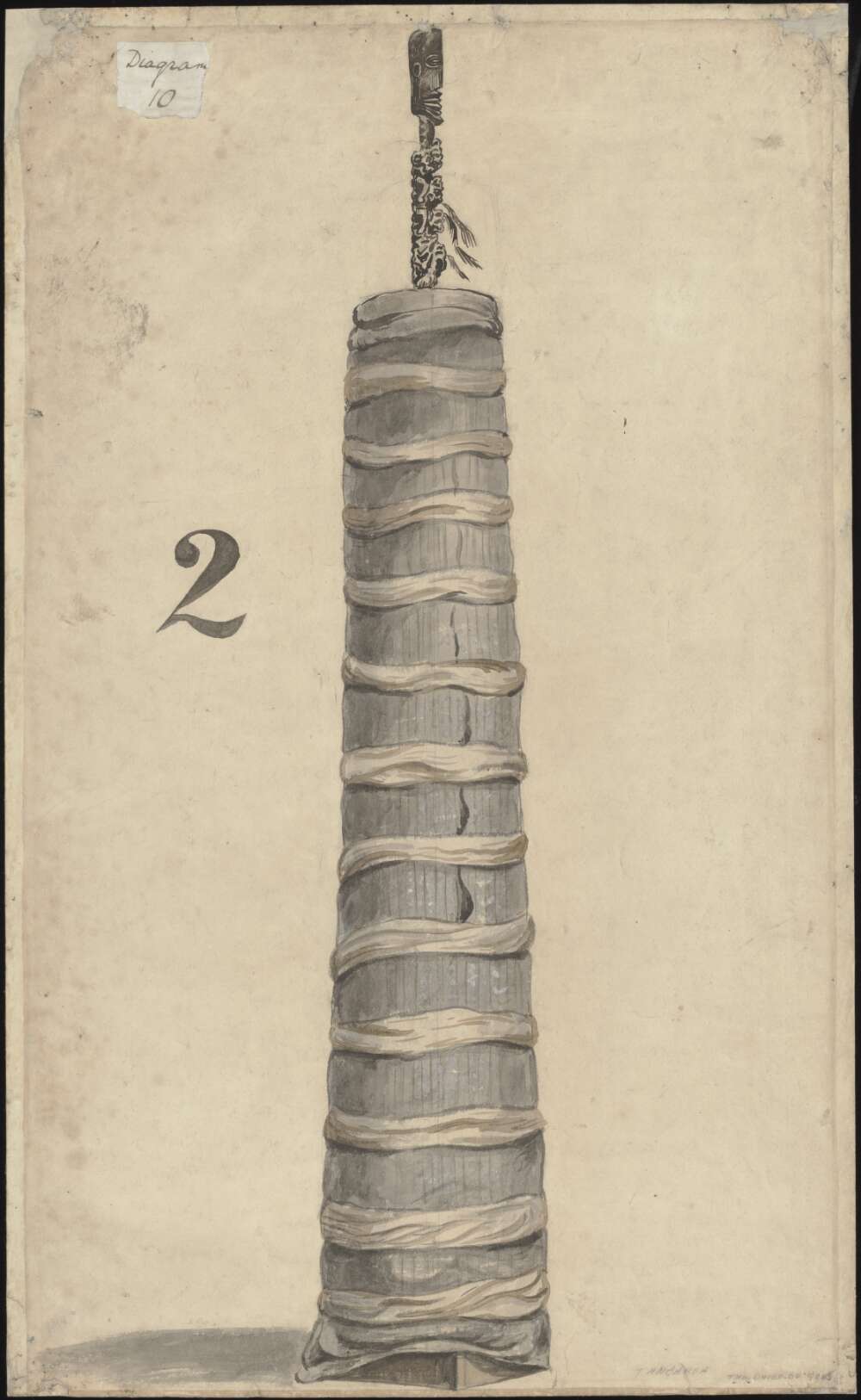

covered with bark cloth, ornamented with black zigzag lines, brought from RAROTONGA, by the lamented Missionary, the Rev. JOHN WILLIAMS. (See his Missionary Enterprises, chap. vii.)

Avarua, Rarotonga, 6 May 1827

Heavy winds and high waves made landing at Avarua extremely challenging – John Williams was almost crushed between the side of the ship and the boat as he reached for his infant son. Mary, his wife, bailed water continuously as others rowed them ashore. Landing on the beach, John described what he saw as ‘the greatest concourse of people I had seen since we left England’. It being a Sunday, worshippers were leaving their chapel, the women dressed in white bark cloth and bonnets, the men in clothes ‘of native manufacture’ and hats.1

Mary and John Williams had come to assist Charles and Elizabeth Pitman to establish their mission on the island. The Pitmans had crossed paths with George Bennet and Daniel Tyerman at New South Wales in 1825 (Chapter 10), who directed them to Rarotonga. Tyerman and Bennet visited the island on their way to Sydney in June 1824, describing its chapel as ‘half finished’ and the people as ‘gentle, upright, and well behaved, attending with diligence to the means of grace, and daily making progess in the arts of civilised life’.2

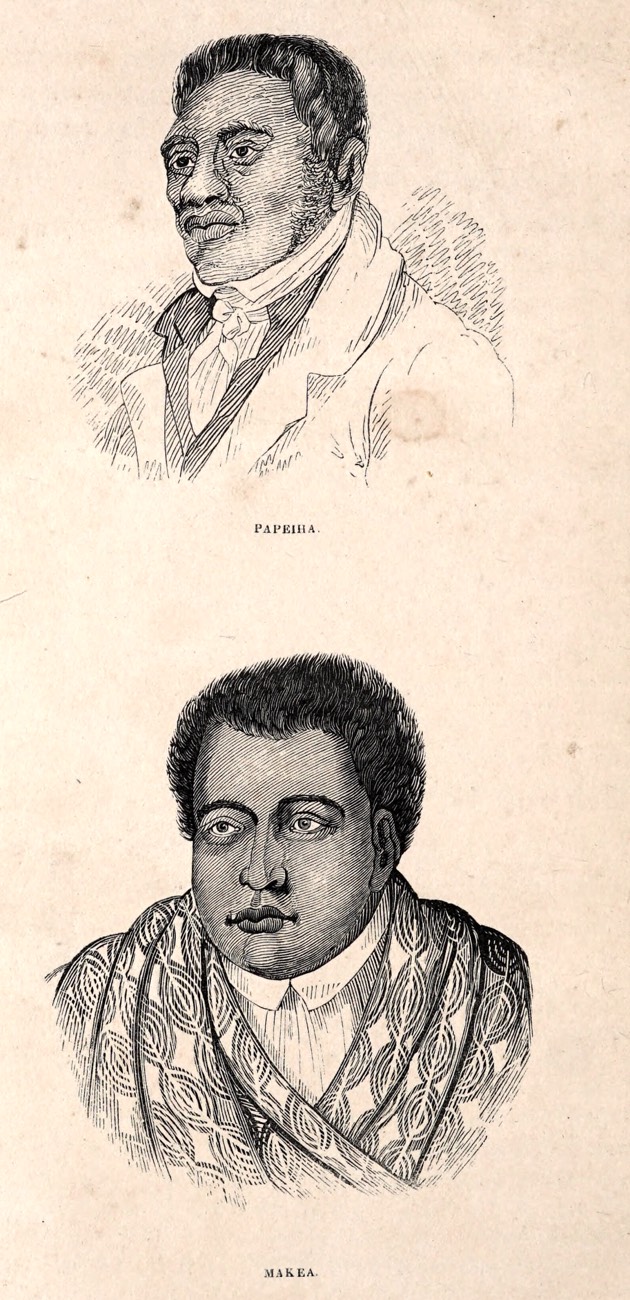

Three days after the arrival of the Pitmans and the Williams, the ship on which they had arrived left because of the rough sea. The following day, the whole community of between two and three thousand people walked to another settlement on the eastern side of the island. Several Rarotongans, including Makea, the ariki (chief or king) at Avarua, offered to carry the many curious possessions brought by the recently arrived Europeans. On arrival at Ngatangiia, they discovered a pair of recently constructed houses, built for Papeiha and Tiberio, preachers from the Society Islands who had lived at Rarotonga for the previous four years. One of these houses was given up for the new arrivals. According to John Williams’ description, published a decade later, in 1837:

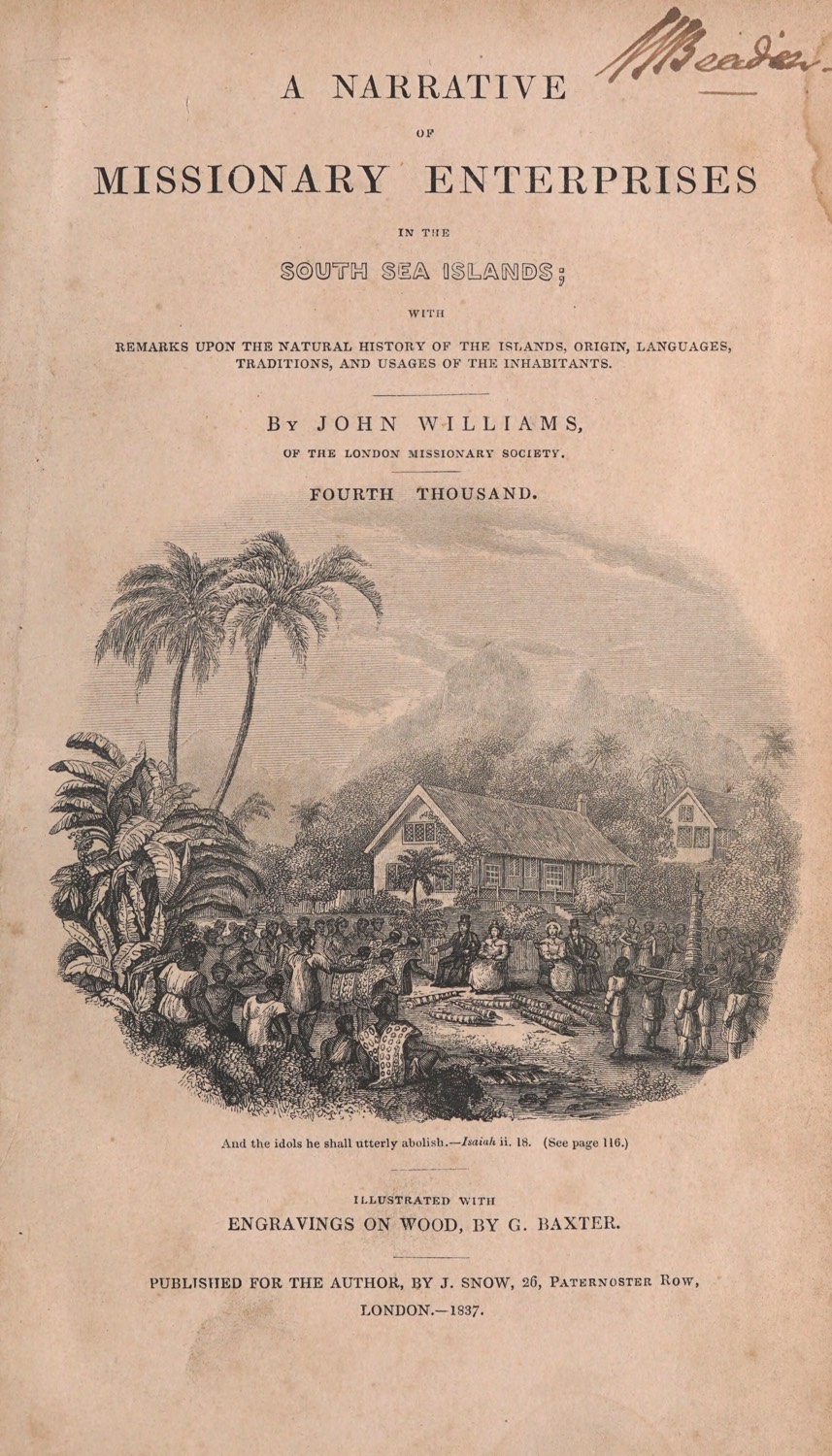

A day or two afterwards, they requested us to take our seat outside the door; and on doing so, we observed a large concourse of people coming towards us, bearing heavy burdens. They walked in procession, and dropped at our feet fourteen immense idols, the smallest of which was above five yards in length. Each of these was composed of a piece of aito, or iron-wood, about four inches in diameter, carved with rude imitations of the human head at one end, and with an obscene figure at the other, wrapped around with native cloth, until it became two or three yards in circumference. Near the wood were red feathers, and a string of small pieces of polished pearl shells, which were said to be the manava, or soul of the god. Some of these idols were torn to pieces before our eyes; others were reserved to decorate the rafters of the chapel we proposed to erect; and one was kept to be sent to England, which is now in the Missionary Museum.3

In Williams’ (1837) book, A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, there is an image on the page after this description, showing what is described by a caption as ‘One of the national idols’, wrapped in layers of bark cloth, alongside its string of shells, or manava, captioned as the ’Soul of the idol’. Empty space on the page is filled by a sketch of ‘The Fisherman’s god’, also from Rarotonga. This ‘Fisherman’s god’, now in the British Museum (Oc,LMS.36), appears to have been emasculated, though whether this happened in Rarotonga is unknown.

Similarly, just as Williams did not describe the ‘obscene figure’ at the bottom of the ancestral pole, known in the Rarotonga language as ki’iki’i, the image in his book avoids showing the phallus with which the twelve foot long pole originally terminated. Whether this had also been removed is unclear.4 In his text, however, Williams notes that:

It is not, however, so respectable in appearance as when in its own country; for his Britannic Majesty’s officers, fearing lest the god should be made a vehicle for defrauding the king, very unceremoniously took it to pieces; and not being so well skilled in making gods as in protecting the revenue, they have not made it so handsome as when it was an object of veneration…5

Described as ‘A Gigantic Idol’ in the catalogue of the Missionary Museum, printed around 1860, which provides this chapter’s title, it stood at the centre of the Missionary Museum for many decades (under the north skylight according to the catalogue), rivalling and ultimately eclipsing John Campbell’s South African Giraffe (Chapter 3). Images of the missionary museum suggest that unlike the image in Williams’ book, its bark cloth wrappings were wider at the bottom than the top, presumably a consequence of its disassembly by British custom officers.6

A few days after the performance of iconoclasm described by Williams, several thousand people assembled for Sunday worship. Half of them had to sit outside the building which served as their temporary chapel. Over the next two months, the entire community worked together to construct a new place to worship. According to Williams, it was ultimately:

one hundred and fifty feet in length, and sixty wide; well plastered, and fitted up throughout with seats… It was a large, respectable, and substantial building; and the whole was completed without a single nail, or any iron-work whatever. It will accommodate nearly three thousand persons.7

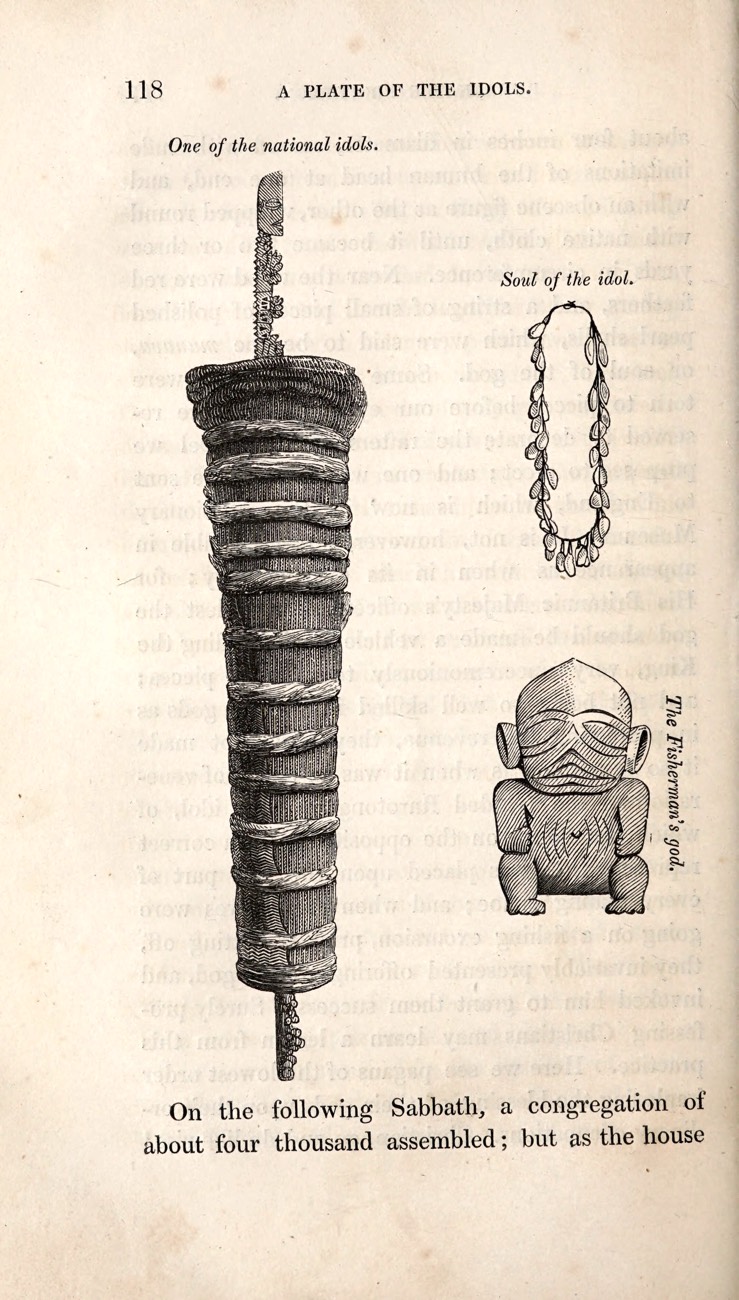

The script for this tale of conversion – the destruction of religious ‘idols’, the adoption of new forms of dress and the building of a new church, overseen from a distance by European missionaries, recapitulates the image produced for Missionary Sketches in July 1819, where it illustrated the conversion of Tahiti under Pomare II (Chapter 4). Given that no Europeans had lived at Rarotonga for any length of time before May 1827, it seems safe to assume that at least part of this script was compatible, or at least comprehensible, in terms of existing Polynesian religious practices.

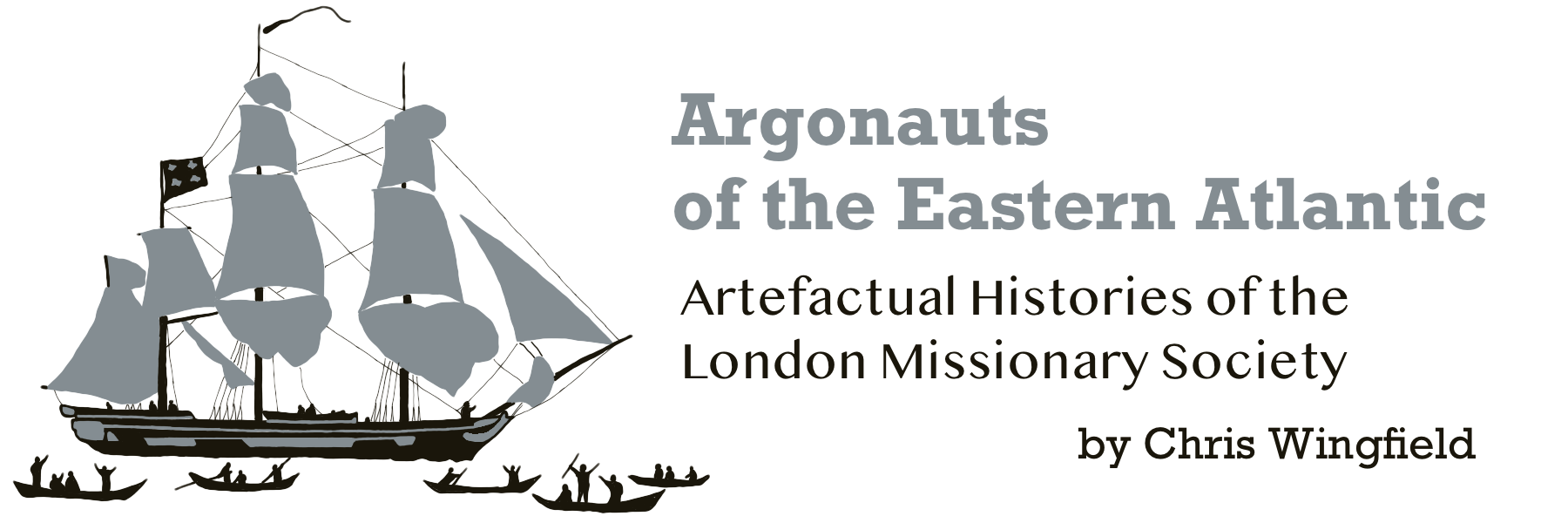

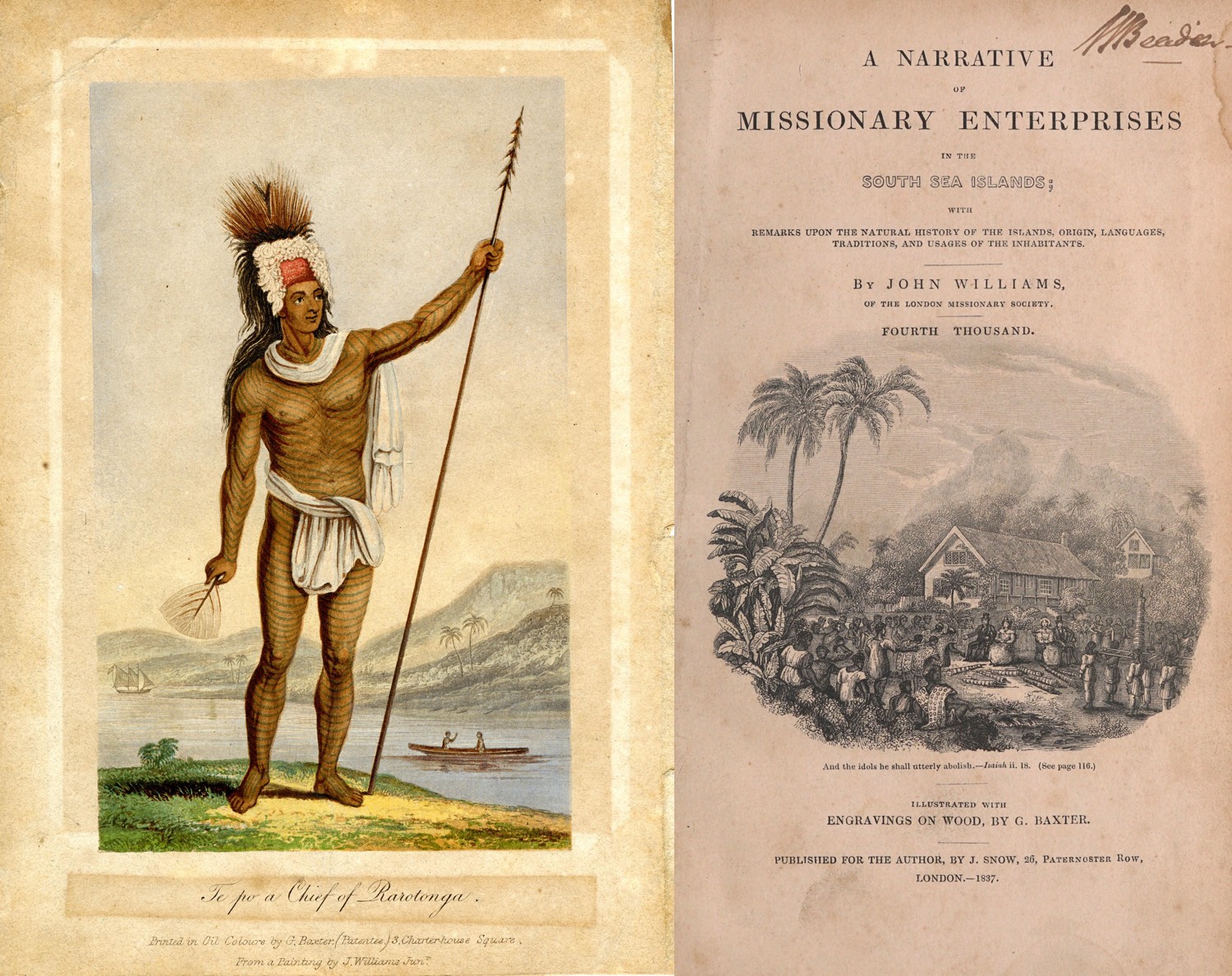

Nearly two centuries after the event that was depicted on the title page of John Williams’ (1837) Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, above a quotation from Isaiah ii, 18 declaring ‘And the idols he shall utterly abolish’, how should best can we understand the conditions that prompted this performance of conversion?

Depiction of the presentation of 'idols' to John Williams at Ngatangiia in May 1827

Woodcut engraving by George Baxter for the title page of John Williams’ A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, published in 1837

Depiction of the presentation of 'idols' to John Williams at Ngatangiia in May 1827

Woodcut engraving by George Baxter

Destruction of the Idols at Otaheite; pulling down a Pagan Altar, and building a Christian Church.

Cover of Missionary Sketches 6, published in July 1819.

John and Mary Williams had arrived in the Pacific ten years earlier, on 17 November 1817, together with four other missionary couples. Inspired by news of Pomare’s ‘overthrow of idolatry at Tahiti’ (Chapter 4), they formed part of a significant reinforcement for the, by then, fairly depleted first generation of European missionaries (four of whom had arrived in the Duff in 1797 and the other four in the Royal Admiral, a convict ship, in 1801).

These additional recruits made it possible to expand European influence beyond the small island of Mo’orea, where British missionaries had stayed for much of the previous decade, sending despatches to London during Pomare’s reconquest of Tahiti including, in 1816, his ‘Idol Gods’ (Chapter 4).

By 1817, the destruction of marae (religious ceremonial enclosures) and the burning of to’o (spiritual vessels) and ti’i (religious sculptures) had spread far beyond Papetoai on Mo’orea, where Pati’i, a priest, first burnt items he was responsible for in 1815. By the middle of the following year, requests for European teachers had arrived from the Leeward islands of Huahine, Ra’iatea, Taha’a and Borabora, where ‘idols’ had also been destroyed and churches constructed. 8

Former students of the missionary school at Papetoai played a key role in taking new practices of reading and praying (converts were initially known as Bure Atua or prayers to God) to the Leeward Islands. 9They were assisted by Tamatoa, ruler of Ra’iatea, one of Pomare’s key allies. By 1816, Tamatoa had overcome Fenuapeho, his rival on the neighbouring island of Taha’a, who attempted to defend the existing religious system.

Since the capture of the Duff in 1799, however, European missionaries had been dependent on others if they wanted to travel by sea.10 In March 1817, the newly arrived mission printing press was transported, together with a number of missionaries, in the canoes of Vara, chief of Afareaitu in the east of Mo’orea.

A start had been made on building a missionary ship, but it was the arrival of a mariner, Captain Nicholson, sent with the new missionaries from London, which prompted the completion of this vessel, a seventy ton brig. Its launch was arranged for 7 December 1817, but when Pomare II threw a bottle of red wine and declared Ia ora na oe e Haweis (Prosperity to you, O Haweis), naming the ship after his principal benefactor in Britain, the smashing glass so alarmed those holding her ropes that they let go, and the Haweis toppled onto her side.11 Righted, she was subsequently launched.

Missionaries were taken to re-establish stations on the main island of Tahiti at Papara, Papaoa and Puna’auia in Atehuru (called Burder’s Point by the missionaries, after the Secretary of the Society in London), as well as at Matavai, the original location of the mission (Chapter 1), abandoned since 1809. In mid-1818, the Haweis transported Ellis, Williams and Threlkeld to Huahine in the Leeward Islands, together with their wives and a printing press.

In September of that year, Williams and Threlkeld persuaded the Active, purchased by Samuel Marsden in 1814 to supply his Church Missionary Society mission at New Zealand, to take them to Ra’iatea together with Tamatoa. Having received numerous requests for books from Paumonaa and Tifai, former pupils at the missionary school at Papetoai, they went to provide support and oversight.12

Under Williams and Threlkeld, as well as for John Orsmond until he left for Bora Bora in 1820, Ra’iatea became an alternative (and rival) centre of missionary operations. All three were zealous missionary recruits of the new generation, suspicious of the compromises arrived at by the older Tahitian missionaries. In a letter written to the Directors in July 1822, following the death of Pomare II, Williams and Threlkeld declared:

Not one native in this Island (Ra’iatea), whose conduct is at all consistent with the Gospel, laments his loss, but rather consider it interposition of God in removing him, in short his whole aim was to grasp at all of the Islands under the pretence of Christianising them.13

Orsmond, in a somewhat embittered letter sent to England after he was dismissed from the LMS in 1849, described Pomare as ‘a beastly sot’:

The King changed his Gods, but he had no other reason but that of consolidating his Government. After his conquest it is true he went by short stages to shew his authority, receive presents from his newly acquired subjects, drink the abundance of native spirits, and then in their inebriety, cast down their Marae and destroy their Gods, thus by strategem taking away from any future rebellion thro the power of the idols which were always leaders in war.14

The early years at Ra’iatea were spent building houses, chapels and bridges, including some on the neighbouring island of Taha’a.15 Williams’ appeal to supporters in Birmingham prompted a donation to assist his work, including:

two Casks, one containing Nails only, the other, Nails, Hammers, Bench Vices, Nippers, Pincers, Saws, Printing Ink and various other Articles16

In May 1819, an auxiliary Missionary Society was established with Tamatoa as president.17

Puna, one of these who spoke at the meeting described the Missionary Society as like the wind:

that makes the heavy ships sail… If there had been none, no ship would have come here with Missionaries. If there is no property, how can Missionaries be sent to other countries, how can the ships sail? Let us then give what we can.18

Tuahine, added:

Whence comes the great waters? Is it not from the small streams that flow into them… I have been thinking that the Missionary Society in Britain is like the great water, and that such little Societies as ours are like the little streams. Let there be many little streams: let not ours be dry. Let missionaries be sent to every land. We are far better off now than we used to be. We do not now sleep with our cartridges under our heads, our guns by our sides, and our hearts in fear…19

Tuahine’s comments capture a sense that the adoption of Christianity was associated with an end to hostilities and the establishment of peace, but this entailed accepting the authority of the leaders who embraced the new religion such as Pomare II at Tahiti and Tamatoa at Ra’iatea.

In March 1821, a canoe arrived at Ra’iatea from Rurutu in the Austral Islands, 560km to the South, where disease had recently decimated the population. Au’ura, leader of the group, was deeply interested by Christian practices, learning to read during the time he spent at Ra’iatea. Four months later, the arrival of a ship, the Hope, tested the Ra’iateans’ commitment to supporting missionary activity by providing an opportunity for the thirty people who had come from Rurutu to return. Au’ura, however, stated that he didn’t wish to return to his ‘land of darkness without a light in his hand’.20

Puna and Mahamene volunteered to go with him, together with their wives, supported by the congregation at Ra’iatea. Along with bark cloth, food, spelling books and gospels, they were given ‘various useful tools’ including razors, knives and scissors. Lancelot Threlkeld arranged for his personal boat to be towed by the Hope, so that it could return with news. He also wrote to London stating:

the Chief [Au’ura] promises their Gods to you we reccommend [sic] him not to burn them but send them prisoners to the Society.21

In a letter also sent in the Hope to the Directors, Tamatoa explained that he had covered up his own ‘evil spirits’ with the intention of sending them to London, but when he fell ill:

some men said to me that I had taken care of the evil spirits, and that was the reason I was overtaken with sickness; I was requested by the people to burn the evil spirits, and I said Burn them, Oro e a Hiro were the two evil spirits that were burned.22

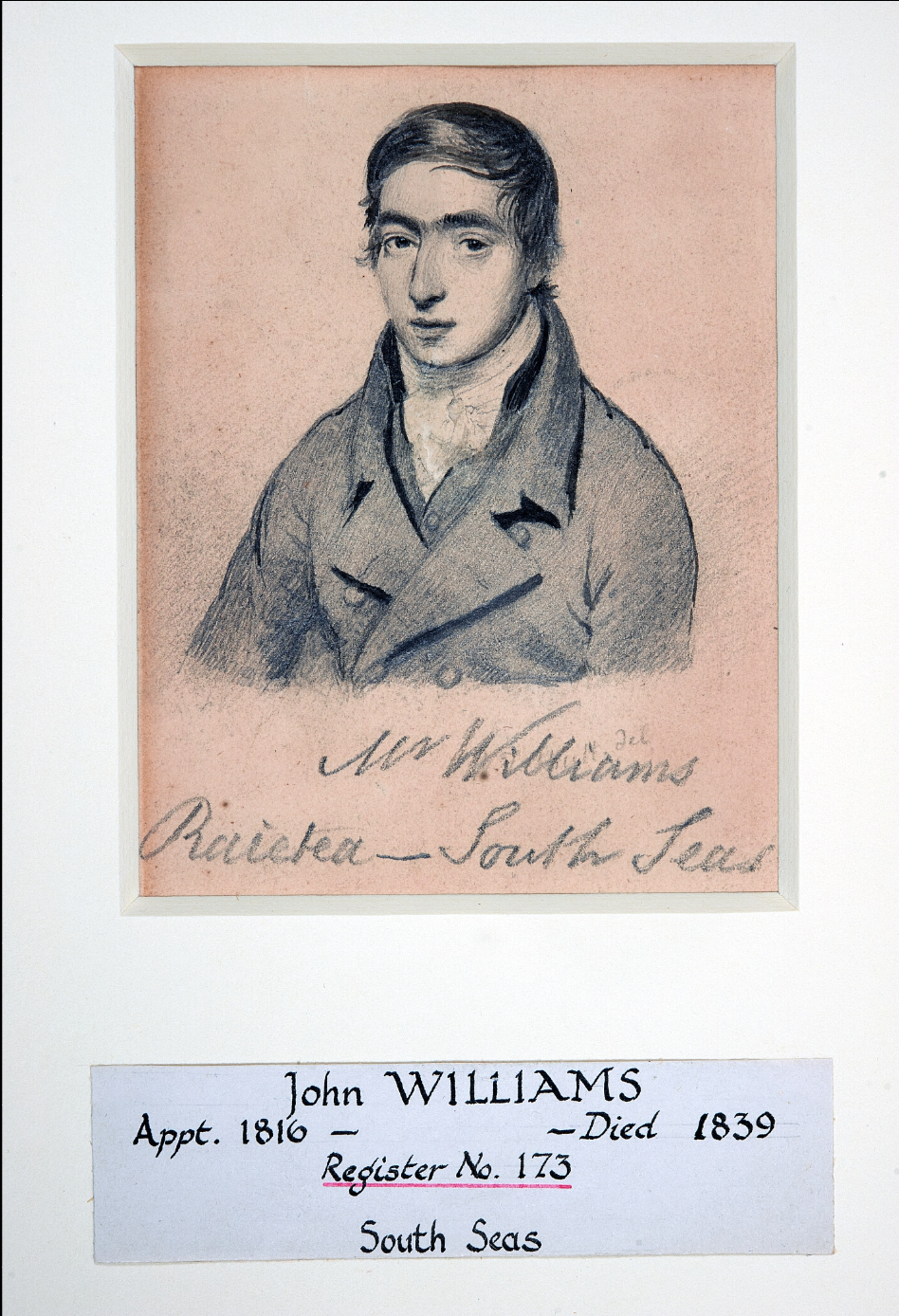

Portrait of the young John Williams

Produced for the London Missionary Society when he was aapointed as a missionary, before leaving for the Pacific.

SOAS Special Collections (CWM/LMS/Home/Miniature Portraits/Box 4/John Williams)

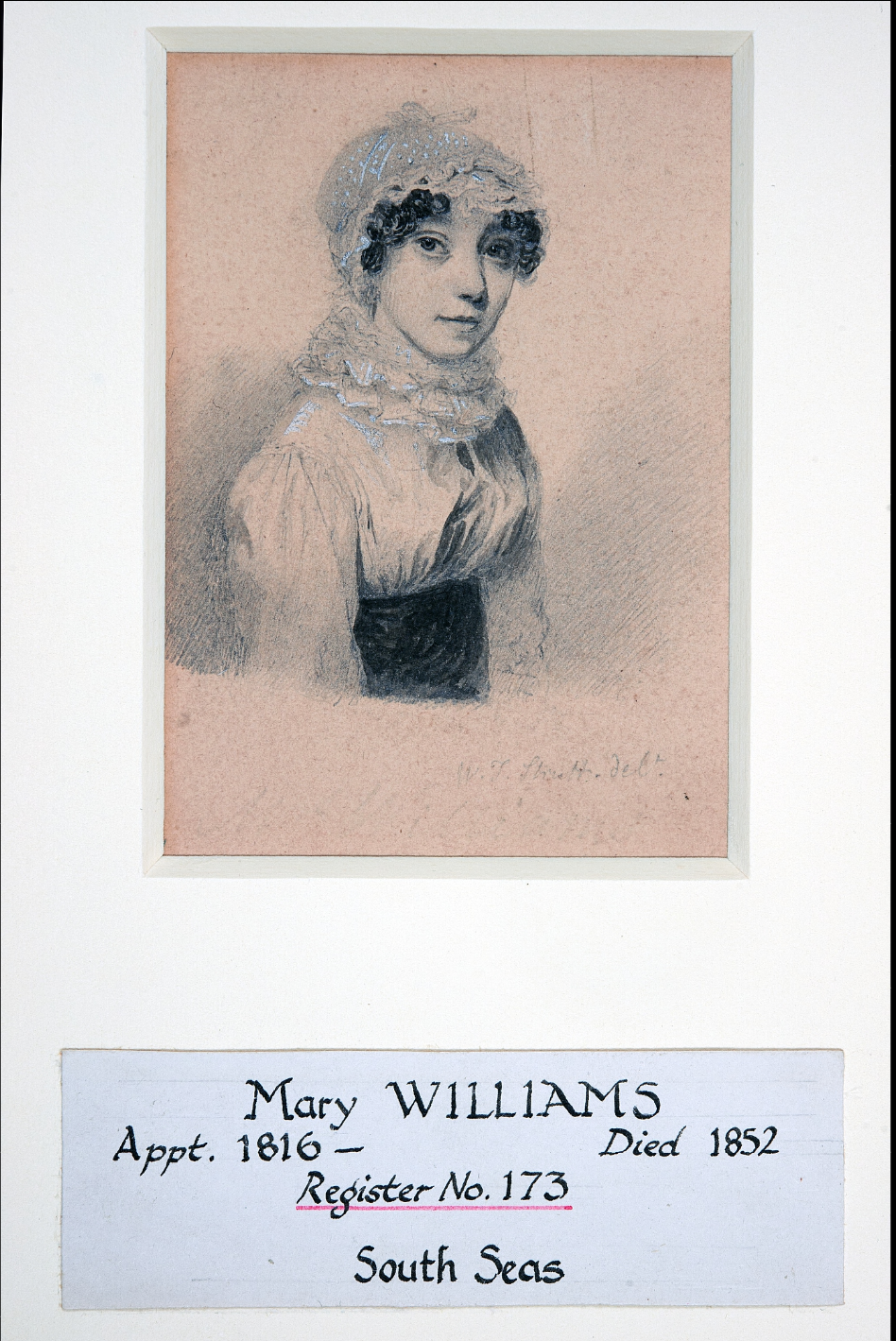

Portrait of the young Mary Williams

Produced for the London Missionary Society when she was appointed as a missionary wife, before leaving for the Pacific.

SOAS Special Collections (CWM/LMS/Home/Miniature Portraits/Box 4/Mary Williams)

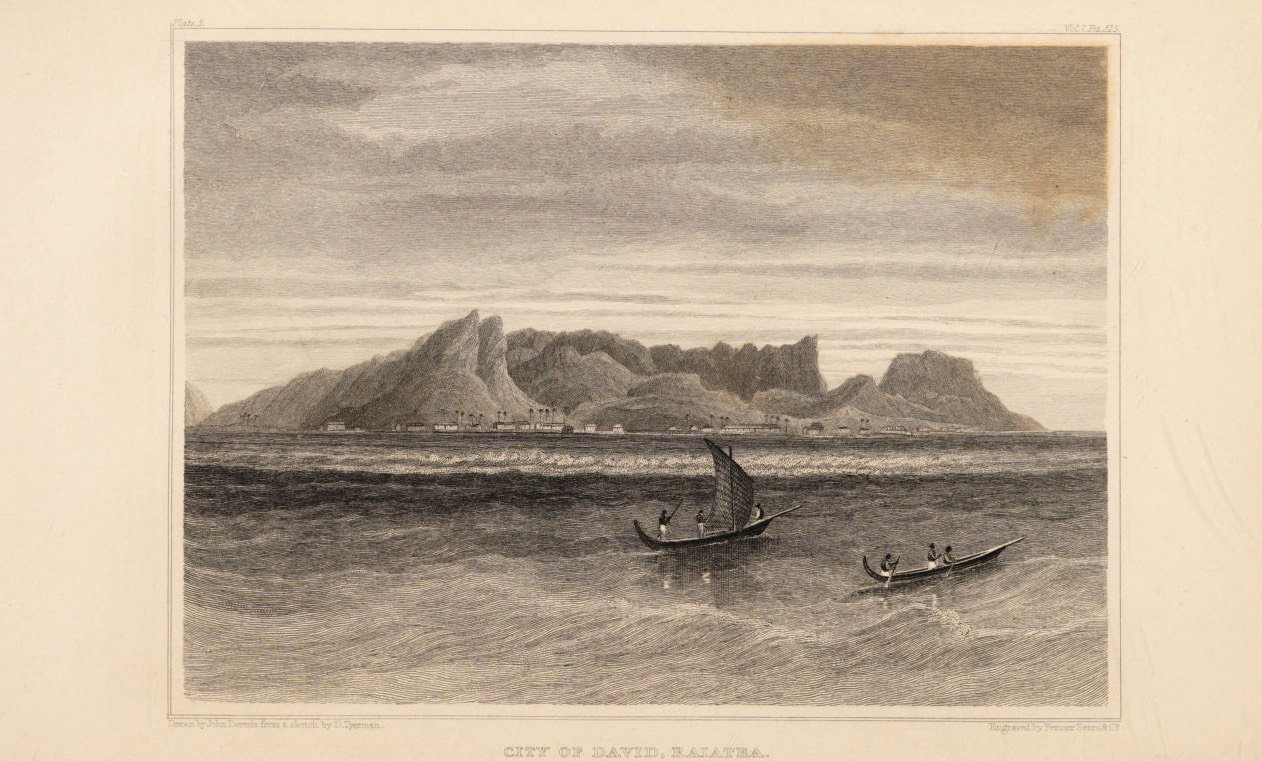

'City of David - Missionary Settlement in the Island of Raiatea'

‘The Chapel is seen above the mast of the canoe; the Mission-house near the centre; on the highest hill on the left is the Po, or Hades of this and of all the other islands [Taputapuātea]. The white surf marks the sitaution of the coral-rocks.’ This was the location of the mission station at Vauaara [Fa’aroa] until 1824.

Engraved by Fenner Sears & Co. Drawn by John Demis from a sketch by D. Tyerman. Published in 1831 in Journal of Voyages and Travel by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq. compiled from original documents by James Montgomery. London: Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis.

Bay in South Sea Island (ships surrounded by canoes)

Part of a collection of 30 large watercolours used on lecture tours in Britain by John Williams during the 1834 and 1837.

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK1224/27

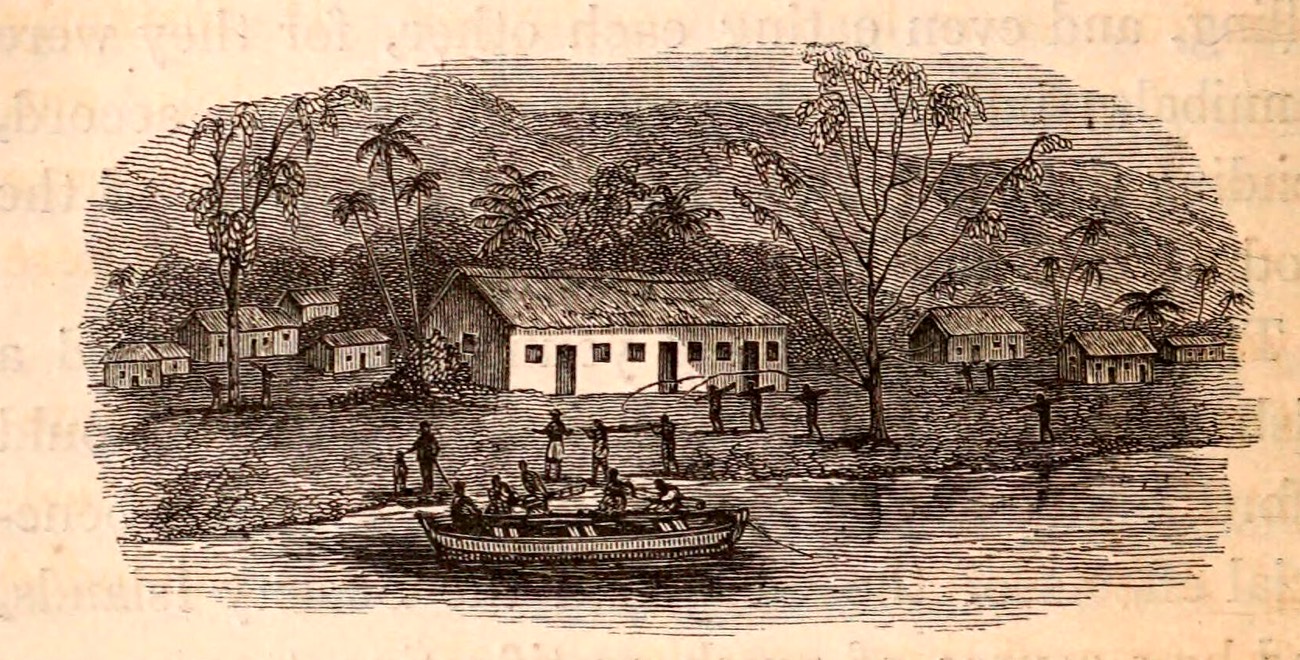

'Settlement at Utumaoro in Raiatea'

This was the location of the mission after 1824. An engraving of this image featured in Missionary Sketches 47 (October 1829).

Part of a collection of 30 large watercolours used on lecture tours in Britain by John Williams during the 1834 and 1837.

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK1224/24

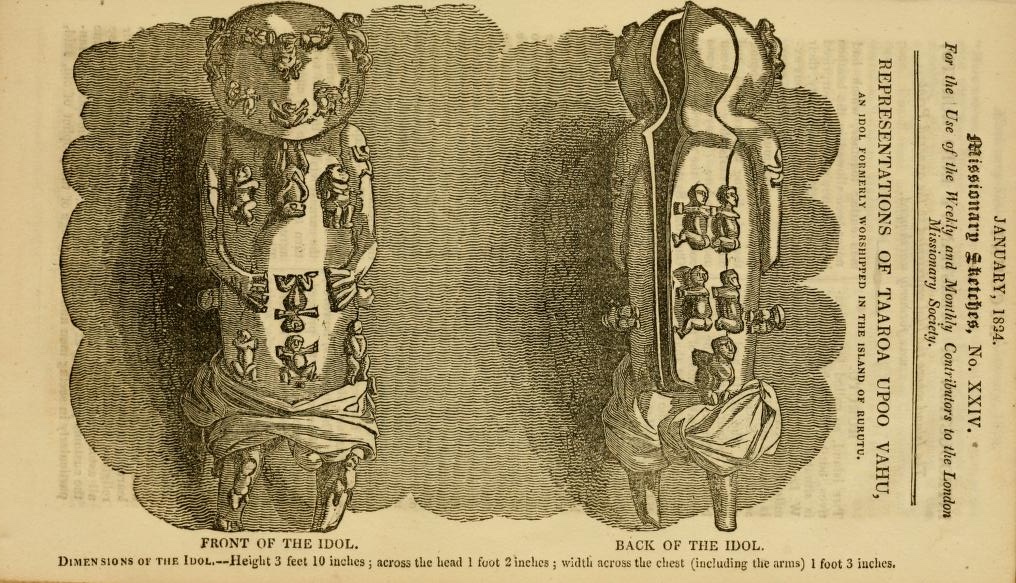

In August 1821, Threlkeld’s boat arrived back at Ra’iatea with letters from Au’ura, Puna and Mahamene, carrying what John Williams described as ’prisoners, the gods of the heathen, taken in this bloodless war, and won by the blood of Him who is Prince of Peace’. A letter sent by Puna and Mahamene described a meeting of ‘the chiefs and king’ at Rurutu when Au’ura proposed that ’the evil spirit be this instant cast into the fire’, suggesting that God had guided him to Ra’iatea ‘where the teachers are’. According to this letter, two men started up ‘inspired by the evil spirit’, stating ‘I have seen the foundation of the firmament, up in the sky. Taaroa brought me forth.’23

Auura then answered the evil spirit thus, ‘Do you leap up then, that we may see you flying up into the sky. Do so now, immediately. Truly thou art even the very foundation of deceit. The people of Rurutu have been completely destroyed through you, and through you alone, and now you shall not deceive us again…24

Puna then advised the assembled men:

prepare one place where you may all eat together, you and your wives and children, and your king, at one eating place, and there the evil spirit who has just now inspired that man shall be completely ashamed: he has no refuge; but cast away every disgraceful thing from among you, for that is the reason he remains among you.25

When communal eating prompted no apparent ill effects, the people of Rurutu ‘boldly seized the gods, and then proceeded to demolish totally the Morais [Maraes], which was all completely effected that day.’ Puna and Mahamene then oversaw the construction of a Chapel, in which Tyerman and Bennet noticed old spears being used ’to support the balustrade of the pulpit staircase’ in November 1822.26

Representations of Taaroa Upoo Vahu (A'a) from Rurutu

Cover of Missionary Sketches 24, published in January 1824.

The evening that Threlkeld’s boat arrived back at Ra’iatea, a meeting was held in the chapel, lit by a great many cocoa nut shell lamps. The evangelists’ accounts from Rurutu were shared and the ‘idols’ exhibited from the pulpit. According to Williams:

One in particular, Aa, the national god of Rurutu, excited considerable interest; for, in addition to his being bedecked with little gods outside, a door was discovered at his back; on opening which, he was found to be full of small gods; and no less than twenty-four were taken out, one after another, and exhibited to public view. He is said to to be the ancestor by whom their island was peopled, and who after death was deified.27

Tuahine, one of the deacons at the church remarked:

Thus the gods made with hands shall perish. There they are, tied with cords! Yes! their very names also are changed! Formerly they were called ’Te mau Atua,’ or the gods; now they are called ’Te mau Varu ino,’ or evil spirits: Their glory, look! It is bird’s feathers, soon rotten; but our God is the same for ever.28

Another speaker observed:

Look at the chandeliers! Oro never taught us any thing like this! Look at our wives, in their gowns and their bonnets, and compare ourselves with the poor natives of Rurutu, when they were drifted to our island, and mark the superiority! And by what means have we obtained it? By our own invention and goodness? No! It is to the good name of Jesus we are indebted. Then let us send this name to other lands, that others may enjoy the same benefits.29

Religion clearly remained a material business for many members of the congregation at Ra’iatea. The wrapping of Christian women in gowns and bonnets could be read as advancement, just as the unwrapping and burning of ‘gods made with the hands’ marked a devaluation. Nevertheless, it is significant that the translated remarks of both Tamatoa and Tuahine refer primarily to ‘spirits’ rather than to ‘idols’, a Biblical term used mostly by European missionaries.

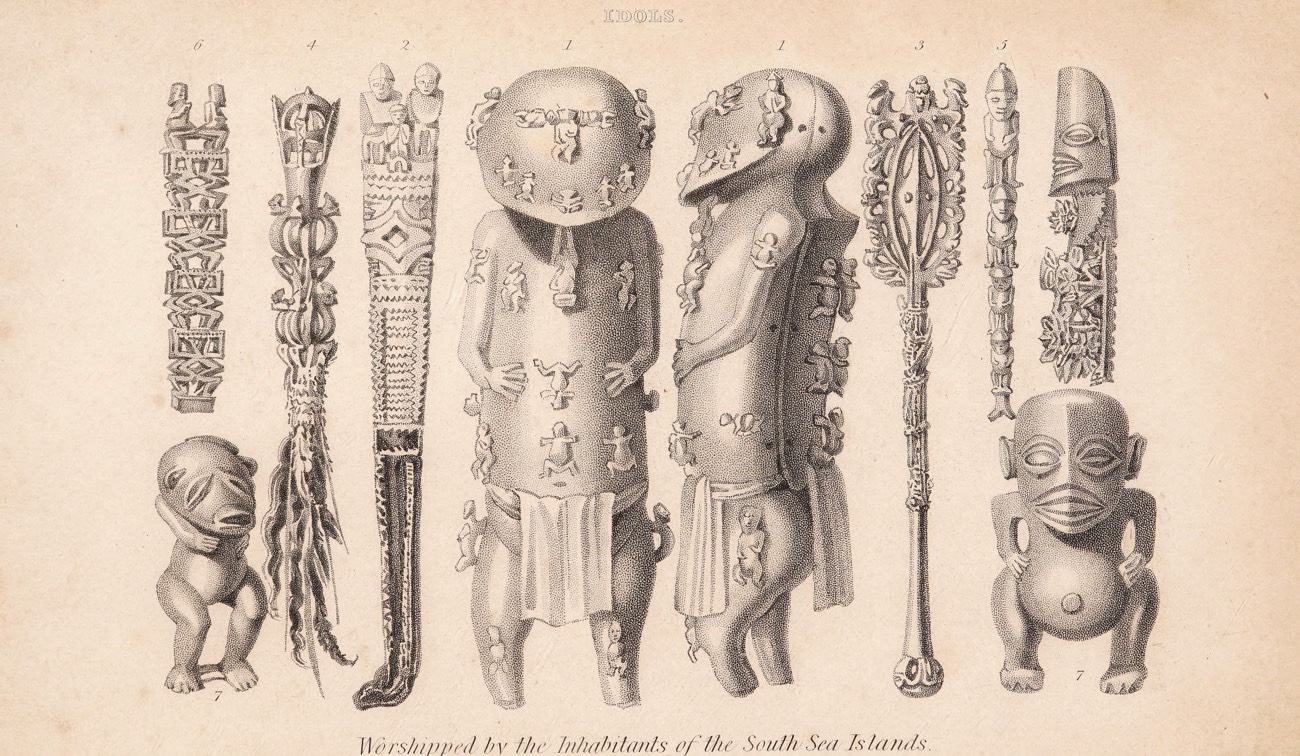

'Idols' worshipped by the Inhabitants of the South Sea Islands

Printed to face the title page of Volume 2 of William Ellis (1829) Polynesian Researches (London: Fisher, Son & Jackson).

Earlier religious practices involving marae, to’o and ti’i appear to have provided the means to manifest and communicate with immaterial spiritual entities – just as printed Bibles embodied the immaterial word of God, and newly built Chapels housed congregations through which the Holy Spirit could act on earth. Describing ti’i (carvings representing spirits) and to’o (pieces of hard wood representing national or family gods), following conversations with a maker of such things at Ra’iatea, William Ellis suggested that:

Into these they supposed the god entered at certain seasons, or in answer to the prayers of the priests. During this indwelling of the the gods, they imagined even the images were very powerful: but when the spirit had departed, though they were among the most sacred things, their extraordinary powers were gone.30

Early nineteenth century Evangelical Christianity, with its emphasis on opening oneself to and accepting, the redeeming power of divine Grace must have been immediately comprehensible to people whose existing religious practices also concerned the channeling divine power in the world, even if they called this mana rather than Grace. This sense of recognition appears to have been mutual, William Ellis declaring:

it is impossible not to feel interested in a people who were accustomed to consider themselves surrounded by invisible intelligences, and who recognised in the rising sun – the mild and silver moon – the shooting star – the meteor’s transient flame – the ocean’s roar – the tempest’s blast, or the evening breeze – the movements of mighty spirits.31

In October 1821, John and Mary Williams traveled to New South Wales in the Westmoreland, a visiting ship, for health reasons.32 Inspired by what had recently taken place at Rurutu, Williams proposed taking further members of his congregation to serve as missionaries at Aitutaki, in what is now the Cook Islands. Members of the Church selected two of their number, Papeiha and Vahapata, for this work.33

At Aitutaki, ‘the Chief’, also called Tamatoa, joined them on deck. When told about the conversion of Tahiti and the Society Islands, he asked about the fate of ‘great Tangaroa’, as well as ‘Koro of Raiatea’ [presumably Oro] and was told that both had been burned.34 He agreed that Papeiha and Vahapata could remain on the island, and it was in the course of this conversation that Williams learned that Rarotonga, of which he had heard much in Ra’iatea, was relatively close at hand.

Williams, who had recently inherited property from his late mother, purchased a vessel at Sydney, the Endeavour, intended to trade tobacco and sugar with the colony on behalf of Tamatoa and other leaders in the islands.35 Williams recruited John Dibbs, second officer of the Westmoreland, to command this ship, which he also planned to use to deliver missionaries to surrounding islands.

Williams returned to Ra’iatea stocked with shoes, stockings, tea-kettles, tea-cups and saucers, as well as tea, hoping that by encouraging tea consumption he could persuade the islanders to grow more sugar. Thomas Brisbane, the Governor of New South Wales also gave cows, calves and sheep to the chiefs and missionaries, as well as two ensigns (British maritime flags) and a pair of church bells.36

In April 1822, while still at Sydney, Williams received letters from Papeiha and Vahapata at Aitutaki, telling him that a number of people originally from Rarotonga had embraced their teachings, and wished to return to their own island. Stopping at Rurutu in May, on the way back to Ra’iatea, Williams found a chapel filled with people wearing bonnets and hats, many of whom had learned to read, as well as plastered houses for the teachers.37

In mid-1823, following the return of the Endeavour from her first trading voyage to Sydney, Williams sailed to Aitutaki with Robert Bourne, as well as four couples from the congregation at Ra’iatea who had volunteered as missionaries, and one from Taha’a.38 They intended to find Rarotonga, but also to leave teachers at other nearby islands. On board the Endeavour, Williams created a letter of instruction for the Polynesian missionaries. The advice it contains suggests he recognised that there was a fine balance to be struck between encouraging the overthrow of existing practices and communicating the good news of Christian salvation, alongside the advantages of new technical skills:

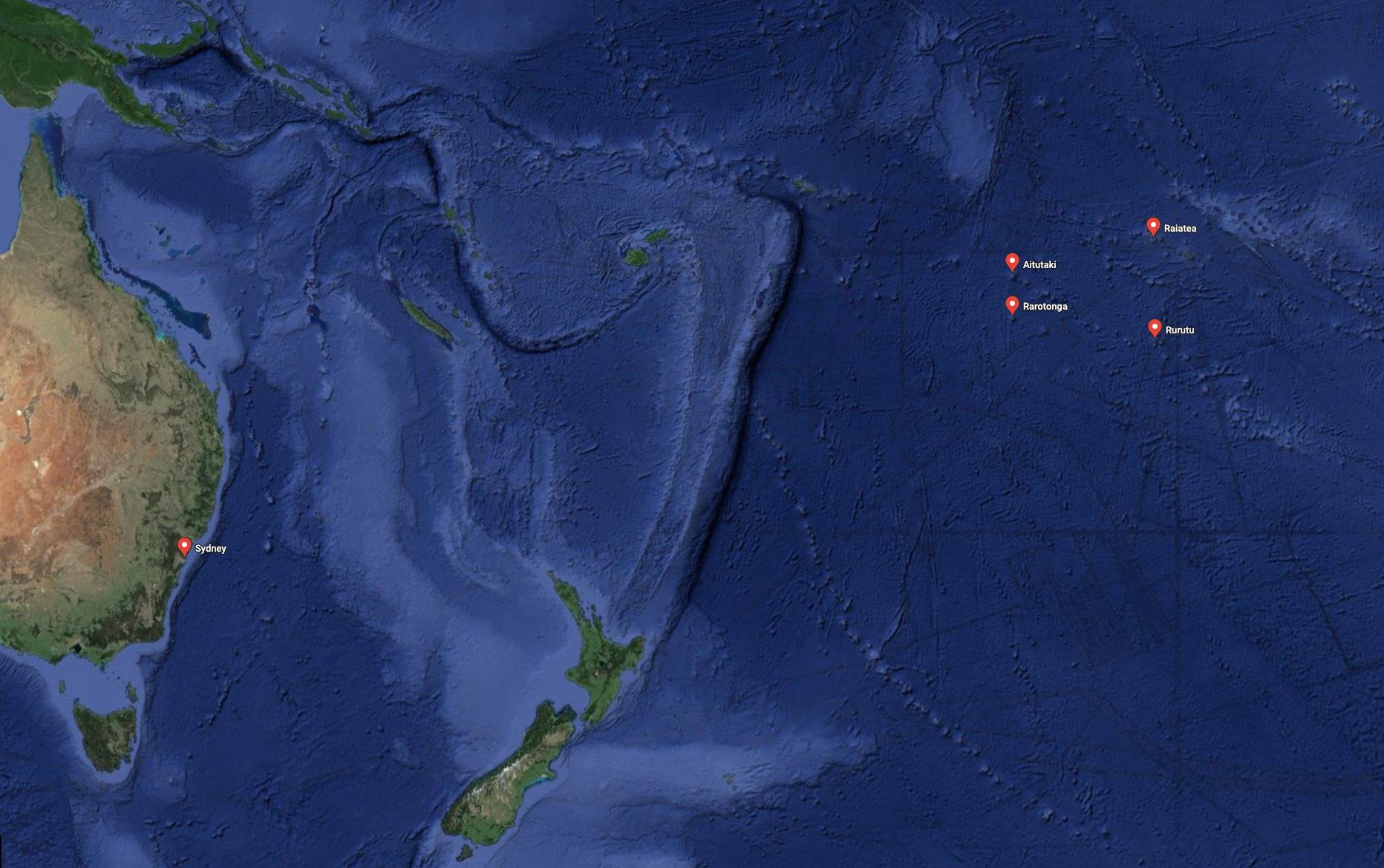

Satellite imagery showing the locations of Ra'iatea. Rurutu, Aitutaki, Rarotonga and Sydney

Locations marked on Google Maps

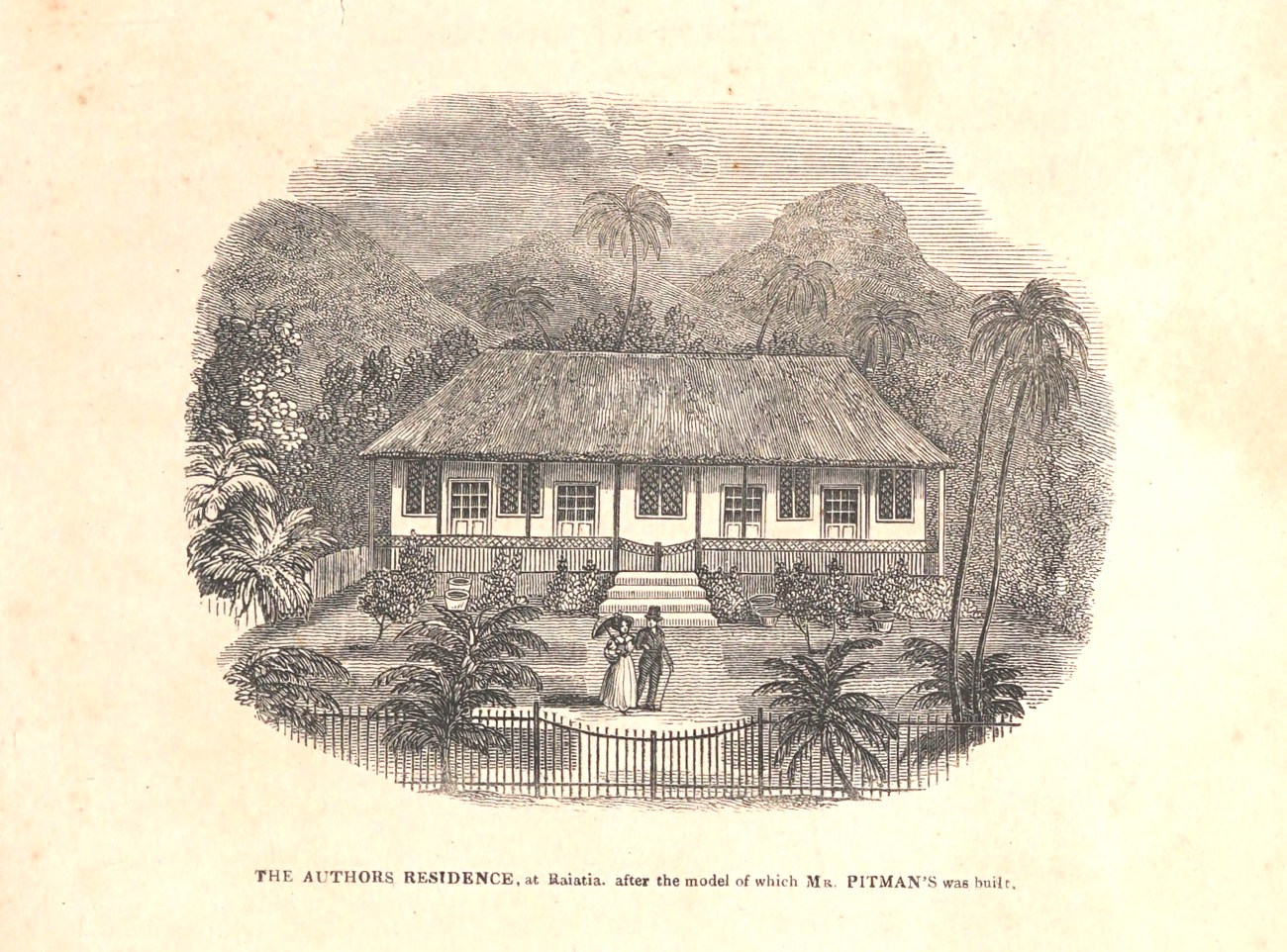

John Williams residence at Ra'iatea, a model for houses subsequently built at Aitutaki and Rarotonga

Woodcut engraving by George Baxter printed opposite p.476 in John Williams’ A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, published in 1837

Remember that this work is the work of the Lord Jesus Christ. It is not to prosper by the strength of man. The Holy Spirit must do the work. Without him, it will not grow…

Do not let the whole of your discourses be directed against the evil spirit; but exalt our Lord Jesus Christ and his Gospel. Tell fully of his great compassion to us, and of the efficacy of his blood to cleanse and save the soul…

All their lesser evil customs, such as going naked, cutting and scratching themselves in seasons of grief, tattooing their bodies, eating raw fish, &c. you will endeavour to cast down; but the greater evils will require your first efforts, and then the smaller…

Have good houses yourselves, and all the little concerns within them, let them be good also… Teach them all you know – to build houses, to do carpentering work, to plaster, and to make bedsteads and seats, to make oil and arrow-root.. Your wives also, let them teach the women to sew, to make bonnets, mats, cloth, &c., that they may appear decent….

If you obtain idols, burn some (but not the best) before their face, lest in case of sickness or other evil, they should think that the gods still in existence inflicted it. The remainder send to Raiatea as a rejoicing to us, and we will send them to England as a rejoicing to them.39

When the Endeavour arrived at Aitutaki on 9 July 1823, canoes approached demonstrating their peaceful intentions by holding up spelling books and European-style hats. Coming ashore, Williams found the maraes had been destroyed and a large plastered chapel (200 ft long) built, together with a five bedroom house for Papeiha and Vahapata.

Encountering a pair of ‘grim-looking gods’ being used as pillars to support a cooking house, he offered a pair of fish-hooks in exchange. Their owner, according to Williams ‘propped up the house, took out the idols, and threw them down; and while they were prostrate on the ground, he gave them a kick, saying, “There – your reign is at an end”.’40

When Williams delivered a sermon in the chapel, Papeiha and Vahapata before the pulpit, dressed in European clothes and facing the congregation. Afterwards, according to Williams, The gods and bundles of gods, which had escaped destruction, thirty-one in number, were carried in triumph to the ship’s boat; and we came off to the vessel with the trophies of our bloodless conquest’.41

Sailing in search of Rarotonga, Papeiha updated Williams on events at Aitutaki over the previous eighteen months, including three periods of armed conflict (suggesting Christian conquest was not as bloodless as claimed). Papeiha and Vahapata had initially been regarded as ‘Two logs of drift-wood, washed on shore by the waves of the ocean’, but their status was enhanced by the arrival of the Endeavour on her way to New South Wales in December 1822, bringing spelling books, axes, pigs and goats from Ra’iatea.42

Soon afterwards, Papeiha called for the destruction of the island’s maraes, the presentation of ‘idols’ to him, and the construction of a chapel. Gleaming white, with plaster made from roasted coral, the new chapel must have dazzled those who had never before seen such a building.

After a week of searching unsuccessfully for Rarotonga, the Endeavour steered for the island of Mangaia. Swimming ashore, Papeiha explained the nature of the ship and its mission. On landing, however, the teachers and their property were seized – a saw broken into three, bonnets dragged through the water, bedsteads seized, and cocoa-nut oil poured over people’s bodies. The teachers’ wives were carried into the woods, only to be rescued when the ship fired a small cannon.

Papeiha, who had been strangled during the attack with a tiputa (a poncho type upper garment of bark cloth, worn by many converts), told the leader who had encouraged them to land what he thought of this behaviour. The man in question, we are told, wept, declaring that all heads were an equal height on his island.43 Months later, the Endeavour returned to Mangaia on its way to New South Wales with Tyerman and Bennet, leaving Davida and Tiere, both unmarried men from Taha’a, as missionaries on the island, which had suffered a severe epidemic following this earlier visit.

After Mangaia, the Endeavour went to Atiu, where John Orsmond had sent a pair of missionaries from Bora Bora a few months previously. They hadn’t made much progress, but when Rongo-ma-Tane, a leader on the island, visited the ship he was told about events at Aitutaki and shown the once powerful ‘idols’ lying in the hold. Attending a service on deck, he determined to bring about the same changes on his island, asking to purchase an axe with which he could cut posts to build ‘God’s house’.44

Persuading Rongo-ma-Tane to stay on board, they sailed to Mitiaro and Mauke, where teachers were landed and instructions given for maraes and ‘evil spirits’ to be destroyed. Williams could not help but see the hand of God in the immediate conversion of these islands. Rongo-ma-tane then directed the Endeavour towards Rarotonga, returning to Atiu with his requested axes, and ‘other useful articles’.

After struggling with contrary winds for several days, the Endeavour was about to return to Ra’iatea when land was sighted from the top of the mast. Papeiha, Vahineino and one of the Rarotongans from Aitutaki went ashore, where it was agreed that teachers should land. Makea, who Williams described as ‘the King’ – ‘about six feet high, and very stout; of noble appearance, and of a truly commanding aspect’ – came aboard the ship. Among the four Rarotonga women and two men who were returning from Aitutaki, he met Tapairu, a close relative.45

Two teachers and their wives spent the night ashore with Papeiha, but returned to the ship early the next morning. Williams was told that a rival chief (possibly Pa Te Pou, ariki of Takitumu) had tried to take one of the female teachers as his wife, but that Tapairu defended the women. Williams was reluctant to abandon the intended teachers to their fate, but Papeiha volunteered to remain at Rarotonga alone if his friend Tiberio was sent to join him. Papeiha waved goodbye to Williams, going ashore in a canoe with just the clothes on his back, his Bible and some spelling books.46

Arriving back at Ra’iatea, ‘as other warriors feel a pride in displaying trophies of the victories they win’, Williams triumphantly hung his ‘prisoners’, ‘the rejected idols of Aitutaki’ from the yard-arms of the Endeavour as they entered the harbour in triumph.47 Once again, the coconut oil chandeliers were lit, and the ‘idols were suspended about the chapel’. Twenty-five were then sent to Tyerman and Bennet, then still at Tahiti and six others directly to the Missionary Museum in England.48

Williams made another trip in the Endeavour, to Rurutu and Rimatara, but this would be his last. Traders at Sydney had persuaded the Governor of New South Wales to apply a duty to sugar cane and tobacco imports, rendering the ship an unprofitable and unsustainable enterprise. In addition, the Directors in London disapproved of Williams involving himself in financial speculation, so the Endeavour was sent to Sydney to be sold. Williams provided the Directors’ with his interpretation of events:

Satan knows well that this ship was the most fatal weapon ever formed against his interests in the great South Sea; and, therefore, as soon as he felt the effects of its first blow, he has wrested it out of our hands.49

Appealing for funds for a replacement, Williams and Threlkeld wrote:

Think not of the expense of such a vessel. Remember the gods are to be her cargo, and your reward. Twice has the Lord God sent you these from hence and from other islands, and your eyes shall see yet greater things.50

'Idol' acquired by John Williams at Aitutaki (together with 'the Snare for catching a god'

Image from British Museum (Oc,LMS.38) alongside woodcut engraving by George Baxter printed on p.65 in John Williams’ A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, published in 1837

British Museum (Oc,LMS.38) & Wellcome Collection EPB/B/54934/1

'Conveying the Idols to the Boat' at Aitutaki

Woodcut engraving by George Baxter printed on p.64 in John Williams’ A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, published in 1837

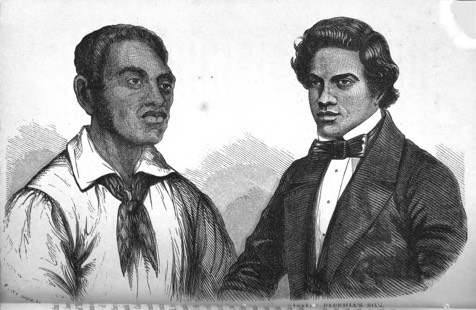

Portraits of Papeiha and Makea

Woodcut engraving by George Baxter printed opposite p.576 in John Williams’ A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, published in 1837

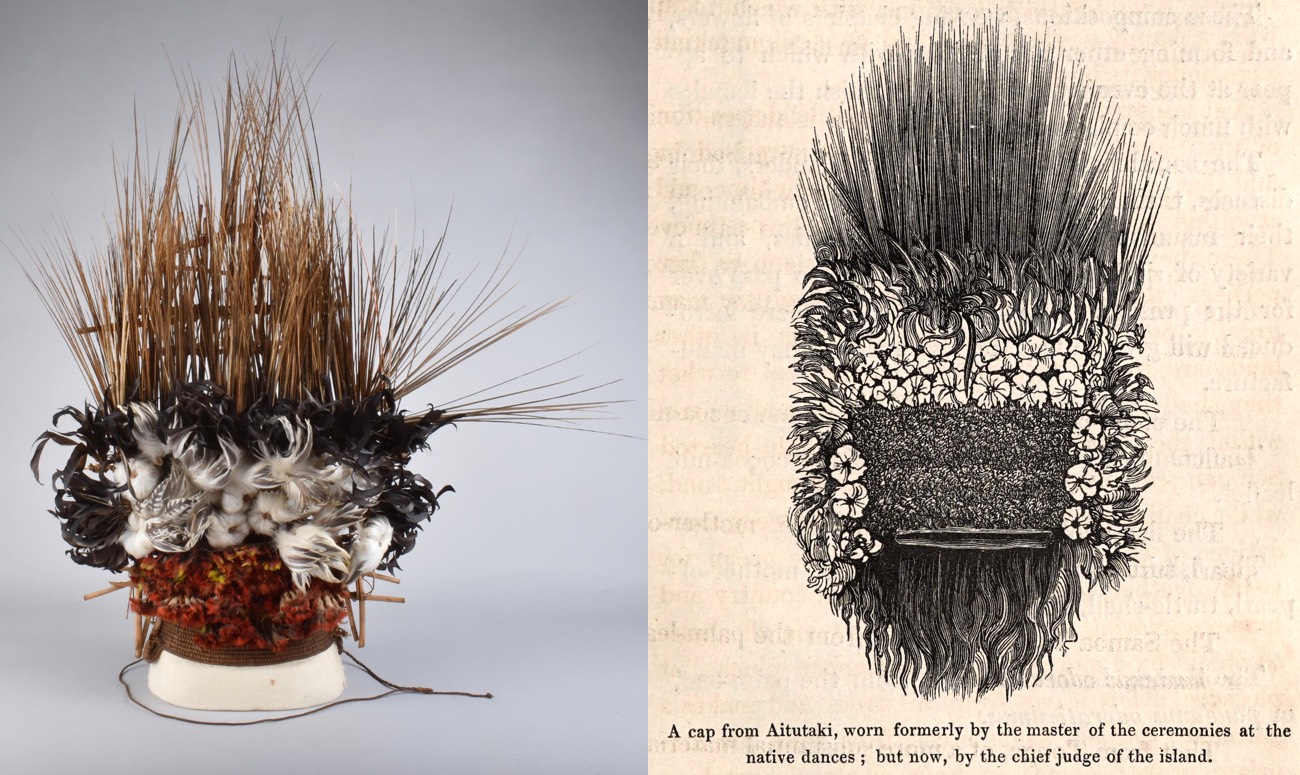

'A cap from Aitutaki, worn formerly by the master of the ceremonies at the native dances; but now, by the judge of the island.'

Image from British Museum (Oc,LMS.56) alongside woodcut engraving by George Baxter printed on p.537 in John Williams’ A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, published in 1837

British Museum (Oc,LMS.56) & Wellcome Collection EPB/B/54934/1

When Williams returned to Rarotonga in May 1827, it had been less than four years since his first visit. When Tyerman and Bennet, together with Threlkeld, visited the island on their way to to New South Wales in late 1824 they reported that the whole population were already engaged in building a six hundred foot long chapel.51 How had Papeiha reorganised the island along Christian principles in such a short period?

Jeffrey Sissons, who has closely examined the establishment of Christianity in Rarotonga, as part of the wider contemporary phenomenon he calls The Polynesian Iconoclasm, has suggested that apparent conversion was ‘as much a material process of indigenisation as it was a local appropriation of foreign ideas’.52 What does he mean? His reconstruction of events is approximately as follows.

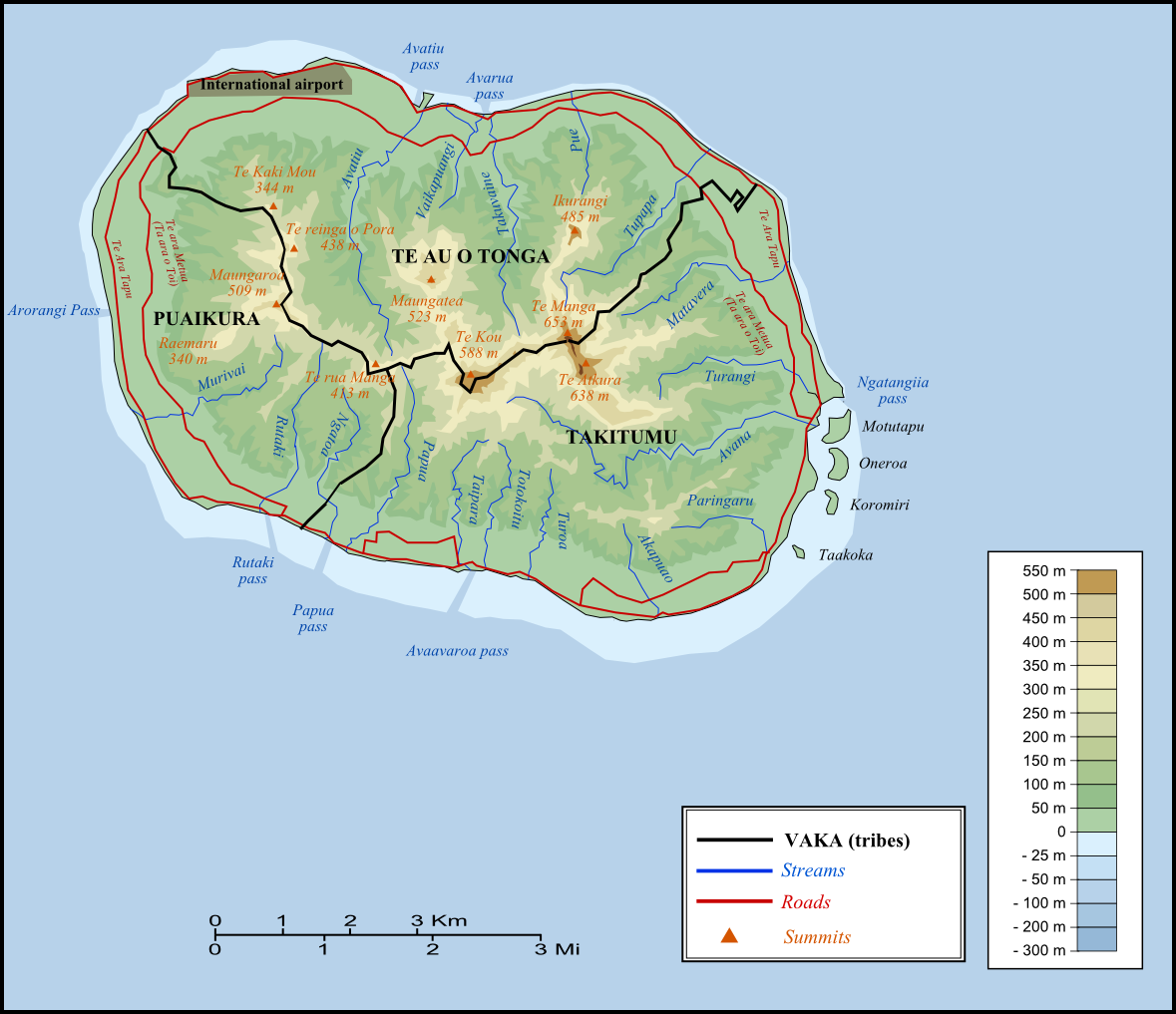

Rarotonga was, and remains, organised into three main districts (vaka, literally canoes, perhaps referencing the arrival of ancestors generations previously): Te Au o Tonga, Puaikura and Takitumu, each overseen by an ariki (high chief or ‘king’). In the decade before Papeiha’s arrival, conflict between the three vaka resulted in the dominance of the Takitumu district. In late July 1823, however, Papeiha arrived at Avarua in the Te Au o Tonga district where Makea was ariki.

By November, Papeiha had assembled a group of high status students, much like the early students at Papetoai, including Makea’s eldest son. After Tiberio arrived in December, the two evangelists toured the island, meeting the leaders of the other districts. When they returned to Avarua, a priest brought his son to be taught, offering to destroy a wooden ‘idol’ in return. Papeiha unwrapped and cut up the image before burning it, roasting and eating bananas in the embers. Within ten days fourteen further ‘idols’ had been destroyed, or at least dethroned. Soon afterwards Tinomana, ariki of Arorangi in Puaikura district, the other defeated region, sanctioned the destruction of his marae.

In March 1824, Pa Te Pou, ariki in the dominant Takitumu region, summoned Papeiha and Tiberio to Ngatangiia to also burn his ‘idols’. Soon afterwards, a feast was held at Avarua in Makea’s district which included a prayer meeting at which ariki and regional chiefs, mata’iapo, wore hats made from bark cloth taken from destroyed ‘idols’. It seems that the three ariki united to form a single large settlement at Avarua, providing feasts that accompanied the construction the large chapel, visited by Tyerman and Bennet in June 1824. The people of the dominant Takitumu district worked on one side of the building, while those of the defeated Te Au O Tonga and Puaikura districts worked on the other. According to John Williams, who visited the chapel:

This, from the circumstances of its erection, was rather an interesting building, but it was destitute of elegance; for, although plastered and floored, and looking exceedingly well at a distance, the workmanship was rough, and the doors were formed of planks lashed together with cnet, which also supplied the place of hinges. One of its most striking peculiarities was the presence of many indelicate heathen figures carved on the centre posts. This was accounted for from the circumstances, that, when built, a considerable part of the people were heathens; and as a portion of the work was allotted to each district unaccompanied by specific directions as to the precise manner of its performance, the builders thought that the figure with which they decorated their maraes would be equally ornamental in the main pillars of a Christian sanctuary.53

When Robert Bourne visited in October 1825 the chapel had recently been plastered, and he was shown ’the cumbrous deities, fourteen in number… now lying like Dagon of old before the ark’. Dagon was an ancient Syrian God, and according to 1 Samuel 5 in the Old Testament, after the Philistines placed the captured ark of the covenant in Dagon’s temple, they returned the next morning the found Dagon fallen face downwards on the group. When Dagon was raised up, he was found the next day fallen again, with both his head and two hands cut off on the threshold of the temple.

Despite such Old Testament precedent, Bourne recognised that a third of Rarotonga’s population still did not support this religious transformation, having pledged allegiance to district chiefs and priests in opposition to the three ariki. Papeiha and Tiberio (armed with a gun) even led an attack on one of the rebel settlements, capturing further ancestral poles by force.

When the population of Avarua decamped to Ngatangiia, following the arrival of Williams and Pitman in May 1827, it was to begin the construction of another chapel in that region. The chapel’s rafters were wrapped in bark cloth taken from the ki’iki’i which had been torn apart, and some of the ancestral poles were themselves hung from its rafters. After this had been completed, a replacement chapel was built at Avarua (1828) and a third at Arorangi (1830). In a statement of unity, the three chapels were linked by a new coastal road, the ara Tapu (sacred path), which replaced the ara metua (ancient path) which had connected the district marae, along which annual processions were typically made.

Just as at Tahiti and Ra’iatea, the adoption of Christianity at Rarotonga was associated with a consolidation and centralisation of chiefly power, materialised in the construction of new churches. These powerfully demonstrated the capacity of ariki to demand and coordinate the labour and resources of others. Resistance continued at Rarotonga, however, and in mid-1828 the church in the Takitumu district was burned down by rebels. Others attempted to burn the church and school-houses at Avarua, defiling the seats of the chiefs and missionaries in the chapel, as well as the pulpit. Only after an epidemic in mid-1830 did violence end. Even in 1831, Charles Pitman could write in his journal that:

The desire of nearly all the people of the island is for their old practices being revived… should the Chiefs again turn their backs to the Teachers the people would for the greater part by far return with them with joy to their heathenish practices.54

'Makea, King of Rarotonga' (ariki of Te Au O Tonga vaka)

Part of a collection of 30 large watercolours used on lecture tours in Britain by John Williams during the 1834 and 1837.

It seems like that the head and shoulders portrait of Makea, above, is based on this painting.

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK1224/6

Watercolour of Rarotongan ki'iki'

It is captioned ‘Tangaroa, chief of idols’, but this seems to be an erroneous attribution. The image suggests the use of a base at the bottom.

Part of a collection of 30 large watercolours used on lecture tours in Britain by John Williams during the 1834 and 1837.

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK1224/8

'Te po, a Chief of Rarotonga' (Pa Te Pou ariki of Takitumu vaka), as readers would have encountered him

Colour image, published opposite the title page of John Williams (1837) A Narrative of Missionary Enterprises. Lithograph, printed in Oil Colours by George Baxter, from a painting by John Williams Junior

This chapter began with the image on the title page of John Williams’ book, showing the presentation and destruction of ‘idols’ in front of of the teachers’ houses at Ngatangiia. It ends by considering this image as readers would have encounetred it in early editions of the book, alongside a colour image produced by George Baxter with the title ‘Te Po, a Chief of Rarotonga’ (Te Pou Ariki of Takitumu).

The image is magnificent, showing the ariki with his spear aloft, holding a fan in the other hand. His noble body is wrapped with tattoos and gleaming white barkcloth, his head adorned by a headdress suggestive of a crown. His centrality within the image seems to demonstrate mastery over both land and sea. In the background, however, a lightly sketched European ship (not evident in the painting, above, on which this seems to have been based) is suggestive of new arrivals.

Viewed in combination with the image on the title page, which would have faced it when opening the book, the images present a contrast. They are images of before and after, suggestive of conversion, evoking images of imaginary tattooed British ancestors before the coming of Christianity. While the conversion of Rarotonga involved transformations in dress, as well as the replacement of one type of religious structure, the marae with another, the chapel, these outward changes likely mask many continuities in the attitudes of the majority of the population.

One undeniable change, however, seems to have been the destruction and removal of wood carvings that evoked ancestral power. The ‘gigantic idol’ at the Missionary Museum (now in the British Museum) appears to have been the only ki’iki’i of its size to survive. In 1853, Isaia Papehia, the fifteen year old son of Papeiha, whose maternal grandfather was ariki of Tinomana, travelled to London with the Rev. William Gill, who had been a missionary on Rarotonga since 1839.55

Visiting the Missionary Museum in London, Isaia encountered the ‘idol of his own grandfather of which he had heard much; the sight of it affected him to tears, and he expressed deep compassion for the people of his native land’.56

According to Rev. Gordon, who returned to Polynesia with him in 1856 in the missionary ship John Williams (Chapter 15), Isaia told the missionary meetings he attended at Sydney and Melbourne that:

He is a great big fellow and when I saw him I was greatly astonished and climbed up and broke off a piece of his nose to take to Rarotonga, and I asked Dr Tidman [Secretary of the LMS] to let me take him back to Rarotonga, to show the young people the queer thing their fathers worshipped, but he say, ’No let you do that.’57

Imagined image of an Ancient Britain (Pict warrior), with stained and painted body

Watercolour image made by John White between 1585 and 1593. Part of an album of drawings which include the first European images of indigenous Americans, made at the ‘Lost Colony’ of Roanoke.

Portrait of Papeiha (left) facing Isaia, his son (right)

From Gems from the Coral Islands by the Rev. William Gill (1856), Volume II, facing p.232

Acknowledgements

I have been incredibly lucky to have worked closely over the years with a number of colleagues with Pacific specialisms over the years, from whom I have learned an enormous amount: Steven Hooper, Karen Jacobs, Nicholas Thomas, Julie Adams, Maia Nuku and Alice Christophe, among others. Nevertheless, as an interloper in the region, any errors or faults are entirely my own.

Recently, I have been grateful for encouragement from Rod Dixon, Jean Mason and Jeffrey Sissons in setting up a collaborative PhD project with the British Museum to further unpack this extraordinary process of conversion and collection through the surviving collections. I am looking forward to their feedback on this chaper, as well as that of Mililani Ganivet, who we appointed to the studentship in 2023.

Comments

This is an experiment in writing – that is intended to stretch the idea of the academic monograph.

I am keen to recognise and incorporate the input and expertise of others into the writing process, so I would welcome any comments or feedback.

Notes

1 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 113: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA113#v=onepage&q&f=false

2 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 121-122: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA95-IA1#v=onepage&q&f=false

3 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 116-117: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA116#v=onepage&q&f=false

4 The ancestral pole (Oc1978,Q.845.a-c) at the British Museum is missing the terminating phallus, but an image at the museum (Oc,A69.41) suggests this may not have always been the case, even if this was not apparent when it was displayed in the LMS museum.

5 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 117: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA117#v=onepage&q&f=false

6 Today, its head is detachable, linked by a threaded metal rod. The British Museum catalogue has photographs showing the head attached to either end of the wrapped figure, suggesting it can be inserted into either end.

7 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 119: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA119#v=onepage&q&f=false

8 Lovett, R. (1899). The History of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895. London, Oxford University Press, pp. 209-211.

9 Tifai and Mohina, brother of Patii (former priest at Papetoai) were at Huahine, while Moeore, son of Tamatoa was at Ra’iatea; Davies, J. (1961). The History of the Tahitian Mission 1799-1830. The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission; with Supplementary Papers from the Correspondence of the Missionaries. C. W. Newbury. Cambridge, The Hakluyt Society, p. 201, p.197.

10 Chief among these, after 1814 was The Active, used by Samuel Marsden to provision Church Missionary Society missionaries at New Zealand from New South Wales. It was on the Active that Williams and other missionaries arrived in 1817.

11 Ellis, W. (1829). Polynesian researches, during a residence of nearly six years in the South Sea Islands : including descriptions of the natural history and scenery of the islands, with remarks on the history, mythology, traditions, government, arts, manners, and customs of the inhabitants. London, Fisher, Son, & Jackson, Volume 1, p. 419: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=OeMRAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=ellis%20polynesian%20researches&pg=PA419#v=onepage&q&f=false

12 Davies, J. (1961). The History of the Tahitian Mission 1799-1830. The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission; with Supplementary Papers from the Correspondence of the Missionaries. C. W. Newbury. Cambridge, The Hakluyt Society, p. 201, p.222, 294, 304-309.

13 Davies, J. (1961). The History of the Tahitian Mission 1799-1830. The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission; with Supplementary Papers from the Correspondence of the Missionaries. C. W. Newbury. Cambridge, The Hakluyt Society, pp. 233-234, fn 1.

14 Davies, J. (1961). The History of the Tahitian Mission 1799-1830. The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission The Hstory of the Tahitian Mission; with Supplementary Papers from the Correspondence of the Missionaries. C. W. Newbury. Cambridge, The Hakluyt Society, p. 349, 350.

15 Letter from Rev. T. East of Birmingham. Missionary Chronicle for January 1821, p.45: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IfEDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA45#v=onepage&q&f=false

16 Thanks – Missionary Chronicle for February 1821, p.92: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IfEDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA92#v=onepage&q&f=false

17 Raiatea. Extract of an Account of the state of the Mission in the Island of Raiatea, and of the General Meeting of the Missionary Society there, Sept. 5, 1819., Missionary Chronicle for August 1820, p.349; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4vADAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA351#v=onepage&q&f=false

18 Raiatea. Extract of an Account of the state of the Mission in the Island of Raiatea, and of the General Meeting of the Missionary Society there, Sept. 5, 1819., Missionary Chronicle for August 1820, p.351; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4vADAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA351#v=onepage&q&f=false

19 Raiatea. Extract of an Account of the state of the Mission in the Island of Raiatea, and of the General Meeting of the Missionary Society there, Sept. 5, 1819., Missionary Chronicle for August 1820, p.351; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=4vADAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA351#v=onepage&q&f=false

20 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 43: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA43#v=onepage&q&f=false

21 Hooper, S. (2007). “Embodying Divinity: The Life of A’a.” The Journal of the Polynesia Society 116(2): 131-179, p. 136.

22 Tamatoa goes on to state: ‘There is one evil spirit; it is a Red Maro, Tero rai Puatata, is the name of this Maro, an evil spirit. Great also is this Red Maro, very many men have been killed in consequence of this Maro, the practice has been continued from of old down to time, and now I know the word of Jesus Christ our Lord’ – this seems to be the Maro mentioned in the account of Tyerman and Bennet (chapter 10).Translation of a Letter from Tamatoa, the King of Raiatea, to the Directors. Missionary Chronicle for February 1822, p. 74-5: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SPEDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA74-IA2#v=onepage&q&f=false

23 Missionary Chronicle for August 1822, p.327-331: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SPEDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA328#v=onepage&q&f=false

24 Missionary Chronicle for August 1822, p.329: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SPEDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA328#v=onepage&q&f=false

25 Missionary Chronicle for August 1822, p.329: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=SPEDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA328#v=onepage&q&f=false

26 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 51: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA51#v=onepage&q&f=false

27 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 44-45: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA44#v=onepage&q&f=false

28 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 45: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA45#v=onepage&q&f=false

29 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 46: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA46#v=onepage&q&f=false

30 Ellis, W. (1829). Polynesian researches, during a residence of nearly six years in the South Sea Islands : including descriptions of the natural history and scenery of the islands, with remarks on the history, mythology, traditions, government, arts, manners, and customs of the inhabitants. London, Fisher, Son, & Jackson, Volume 2, p. 203: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=hOMRAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=ellis%20polynesian%20researches&pg=PA203#v=onepage&q&f=false

31 Ellis, W. (1829). Polynesian researches, during a residence of nearly six years in the South Sea Islands : including descriptions of the natural history and scenery of the islands, with remarks on the history, mythology, traditions, government, arts, manners, and customs of the inhabitants. London, Fisher, Son, & Jackson, Volume 2, p. 198: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=hOMRAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=ellis%20polynesian%20researches&pg=PA198#v=onepage&q&f=false

32 The Westmoreland had recently taken a party of settlers to South Africa, and then returned Rev. Thomas Kendall, Waitkato and Hongi Hika to New Zealand, following their visit to Britain.

33 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 38: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA38#v=onepage&q&f=false

34 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 52: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA52#v=onepage&q&f=false

35 Prout, E. (1843). Memoirs of the life of the Rev. John Williams, missionary to Polynesia. London, John Snow, p.150-151: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=prout%20memoirs%20of%20the%20life%20of%20john%20williams%201843&pg=PA150#v=onepage&q&f=false

36 Prout, E. (1843). Memoirs of the life of the Rev. John Williams, missionary to Polynesia. London, John Snow, p.152: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=prout%20memoirs%20of%20the%20life%20of%20john%20williams%201843&pg=PA152#v=onepage&q&f=false

37 Prout, E. (1843). Memoirs of the life of the Rev. John Williams, missionary to Polynesia. London, John Snow, p.163: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=prout%20memoirs%20of%20the%20life%20of%20john%20williams%201843&pg=PA163#v=onepage&q&f=false

38 These included Paumoana (a former scholar at Papetoai) and Mataitai, intended for Aitututaki, as well as Vahineino & Fanauara for Rarotonga.

39 Prout, E. (1843). Memoirs of the life of the Rev. John Williams, missionary to Polynesia. London, John Snow, p. 172-178, Letter written on the Endeavour, July 6 1823: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=prout%20memoirs%20of%20the%20life%20of%20john%20williams%201843&pg=PA172#v=onepage&q&f=false

40 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 64-65: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA64#v=onepage&q&f=false

41 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 63-64: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA63#v=onepage&q&f=false

42 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 69: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA70#v=onepage&q&f=false

43 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, pp. 77-81: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA77#v=onepage&q&f=false

44 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, pp. 87: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA87#v=onepage&q&f=false

45 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, pp. 101: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA101#v=onepage&q&f=false

46 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, pp. 101-103: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA102#v=onepage&q&f=false

47 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 107: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA107#v=onepage&q&f=false

48 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 108-110: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA108#v=onepage&q&f=false

49 Prout, E. (1843). Memoirs of the life of the Rev. John Williams, missionary to Polynesia. London, John Snow, p.194: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=prout%20memoirs%20of%20the%20life%20of%20john%20williams%201843&pg=PA194#v=onepage&q&f=false

50 Prout, E. (1843). Memoirs of the life of the Rev. John Williams, missionary to Polynesia. London, John Snow, p. 196: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=prout%20memoirs%20of%20the%20life%20of%20john%20williams%201843&pg=PA196#v=onepage&q&f=false

51 Montgomery, J. 1831. Voyages and Travels by the Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennet, Esq… Compiled from Original Documents. Frederick Westley and A.H. Davis. Volume 2: 121-122: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=T55LAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=tyerman%20bennet&pg=PA95-IA1#v=onepage&q&f=false; A year later, the Haweis, now owned by Campbell & Co, Sydney traders who also purchased the Endeavour, was hired for a follow up visit, but it was Robert Bourne rather than John Williams who was selected by lot to go.

52 Sissons, J. 2007. “From Post to Pillar: God-Houses and Social Fields in Nineteenth Century Rarotonga.” Journal of Material Culture 12(1): 47-63; Sissons, J. 2014. The Polynesian Iconoclasm, Berghahn. The account in the section that follows is largely taken from Sissons’ account.

53 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 123-124: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&vq=idol&pg=PA123#v=onepage&q&f=false

54 Pitman, Journal, ms. 6 vols, Sydney, State Library of New South Wales: 1831: 340; cited by Sissons, J. 2007. “From Post to Pillar: God-Houses and Social Fields in Nineteenth Century Rarotonga.” Journal of Material Culture 12(1): 59.

55 When I completed by PhD in 2012, I had found a reference to Gill reporting that the young Rarotongan v’who had to come to this country to see an idol, in the Missionary museum’, I am extremely grateful to Rod Dixon whose Blog post for SOAS Special Collections (https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/archives/2022/03/28/part-3-cook-islander-missionaries-recovering-hidden-histories-from-missionary-archives-isaia-papehias-travels-in-britain/) made it clear who this young man was, and provided additional references which allow us to come closer to what Isaia Papeihia thought of the encounter ; Gill, W. (1855). Fifty-first Anniversary of the British and Foreign Bible Society. The Christian observer, Thomas Hatchard: 525-556; p. 554.

56 Saunders Newsletter 5 October 1863, cited in Rod Dixon (2022) Cook Islander missionaries: recovering hidden histories from missionary archives: Isaia Papehia’s travels in Britain: https://blogs.soas.ac.uk/archives/2022/03/28/part-3-cook-islander-missionaries-recovering-hidden-histories-from-missionary-archives-isaia-papehias-travels-in-britain/

57 Gordon, G. (1863). The Last Martyrs of Erromanga. Halifax, Nova Scotia, Macnab & Shaffer, p.237: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=CAMFAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA106&dq=The+Last+Martyrs+of+Erromanga&hl=en&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjTlpDZ08aFAxV-VkEAHbuEDmIQ6AF6BAgKEAI#v=onepage&q&f=false