that belonged to two native Roman Catholics, who embraced the Christian religion, and sent the same to the Missionary Society

Bangalore, 23 July 1825

The inclusion of this item in the Missionary Museum illustrates a confrontation between Protestant missionary activity and Catholicism which occurred in many places around the world, but is also suggestive of a longer conflict in relation to the function of religious images, beginning in Europe itself. This conflict underpinned the northern European Reformation of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in which Protestantism took shape, and seems to have conditioned the way that LMS missionaries responded to religious ‘idols’, whenever and wherever they were encountered.

Writing about missionary encounters in the Dutch East Indies, now Indonesia, Webb Keane has described this conflict in terms of a clash of semiotic ideologies, suggesting that Protestantism developed a moral narrative of modernity, by which people were understood to be progressively emancipated through their detachment from material forms – a narrative that shaped notions of ‘fetishism’ later in the nineteenth century and arguably continues to underpin contemporary imaginings of secular modernity.3

In many ways it is The Virgin Mary and Child, among all the artefacts listed in the 1826 catalogue, that allows us to unpack the fundamental problem that the London Missionary Society had with ‘idols’ – objects that formed a focus for acts of religious worship – and the reasons these became a dominant focus for missionary collecting during the middle of the nineteenth century.

No original images survive

This is a ghost image for an artefact we know existed, based on a 17th – 18th century Indo-Portuguese ivory Madonna and Child

Following the re-opening of the Missionary Museum at Austin Friars in August 1824, the considerable costs of ‘building the museum’ (£417) generated concern within the Society.4 Should funds raised to support overseas missionary work be used to enable the preservation and display of artefacts in London? Writing from Raiatea in the Pacific on 20 November 1823, the missionaries Lancelot Threlkeld (Chapter 10) and John Williams (Chapter 12) declared as part of their appeal for a missionary ship:

Did you know the state of the surrounding islands, how ripe they are for the reception of the gospel, you would sell the very gods out of your Museum, if it were necessary to afford the means of carrying the glad tidings of salvation to those now sitting in darkness.5

A catalogue of the museum’s contents was compiled and printed, sales of which were intended to ‘to diminish the expense incurred by the preparation and support of the Museum’.6 The catalogue’s price was not fixed, but left to the ‘liberality’ of museum visitors, with a donations box located in the museum.7 By May 1825, the Missionary Chronicle reported that this had returned 57 pounds 7shillings and 5 pence.8

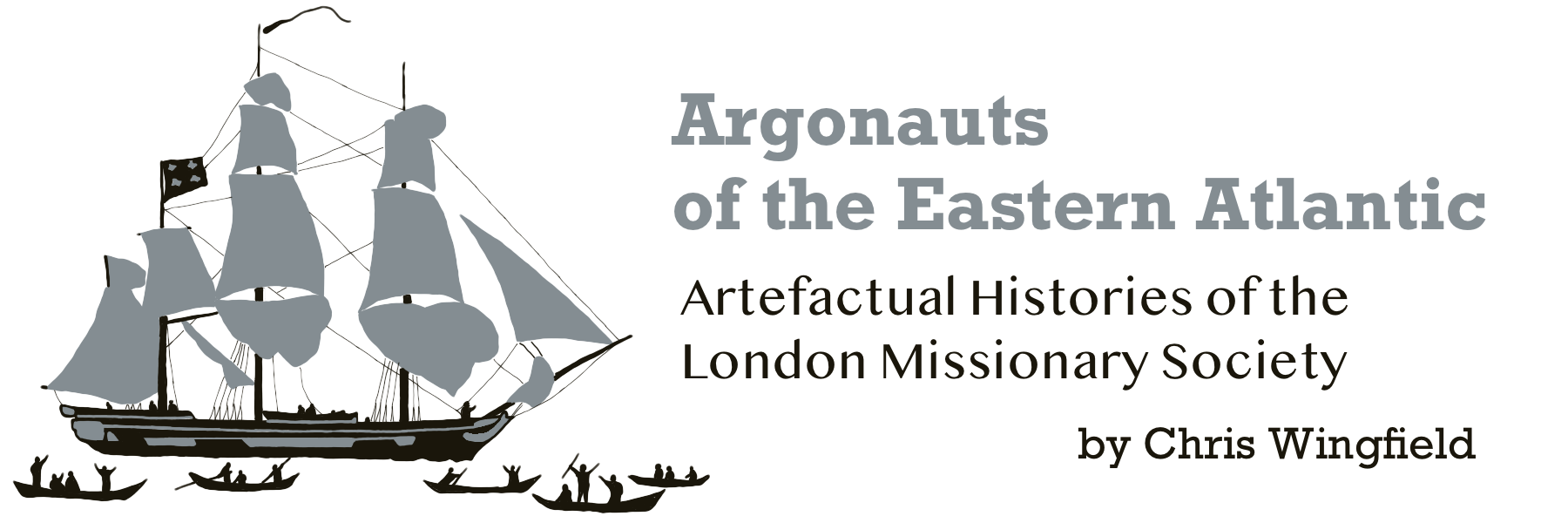

Sadly, there are no known copies of this original 1824 catalogue, but the British Library retains a copy of the slightly later 1826 version.9 This makes it possible to gain a sense of how the collections had grown in the twelve years since John Campbell returned to Britain from South Africa with his giraffe (Chapter 3), as well as many other things, initiating the establishment of the Missionary Museum.

The title page of the catalogue provides a guide to what may be found in the museum, listing three main categories:

- Specimens in Natural History

- Various Idols of Heathen Nations

- Dresses, Manufactures, Domestic Utensils, Instruments of War, &c. &c. &c.

This is followed by an “Advertisement” providing more background on the museum and its collection, explaining that the articles composing the museum were supplied chiefly by Missionaries of the London Missionary Society, with a few others being donations from ‘benevolent travellers, or friendly officers of mercantile vessels’.10 It then explains the three categories of material set out on the previous page, suggesting that:

The Missionaries rightly judged that the natural productions of the distant countries in which they reside would be acceptable at home, especially to the juvenile friends, and to others who may not have opportunity of viewing larger Collections.11

Natural History, although it formed a significant dimension of John Campbells’ original collections, are effectively dismissed as curiosities chiefly of interest to children. It then goes on:

The efforts also of natural genius, especially in countries rude and uncivilised, afford another class of interesting curiosities; whilst they prove how capable even the most uncivilised of mankind are of receiving that instruction which it is the study of Missionaries to communicate.12

The ‘Dresses, Manufactures, Domestic Utensils and Instruments of War, &c. &C. &c.’, through examples such as finely worked samples of bark cloth brought by William Ellis from Hawaii (Chapter 7), essentially demonstrate potential – a capacity for conversion, but also to be schooled in civilisation – though this argument seems to have concentrated on ‘countries rude and uncivilised’ – which in this context seems to have referred largely to Africa and the Pacific.

Presumably penned by a professional preacher, the Advertisement altered the order outlined on the title page so that the third category to be described delivers the rhetorical hammer blow in a new paragraph:

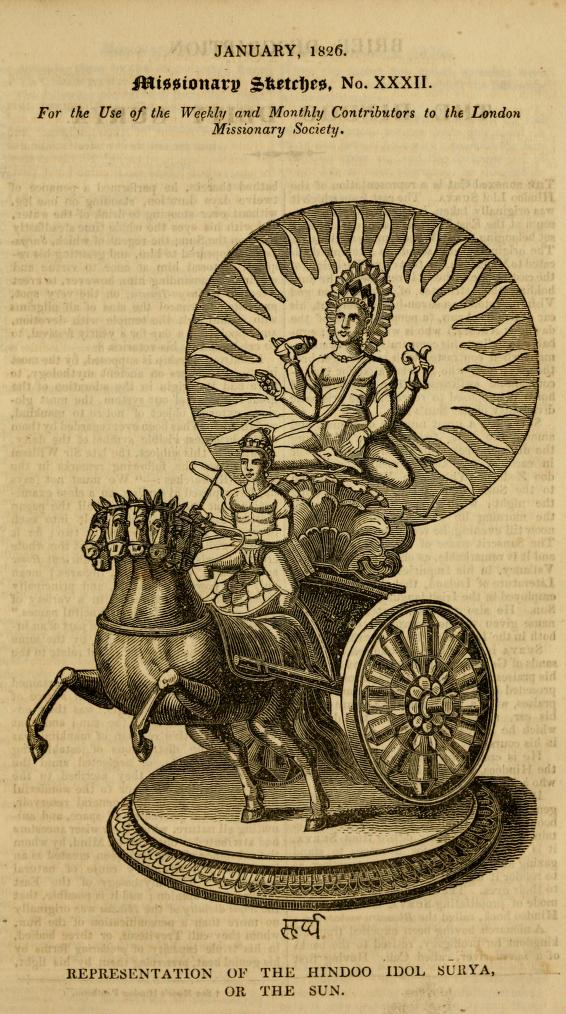

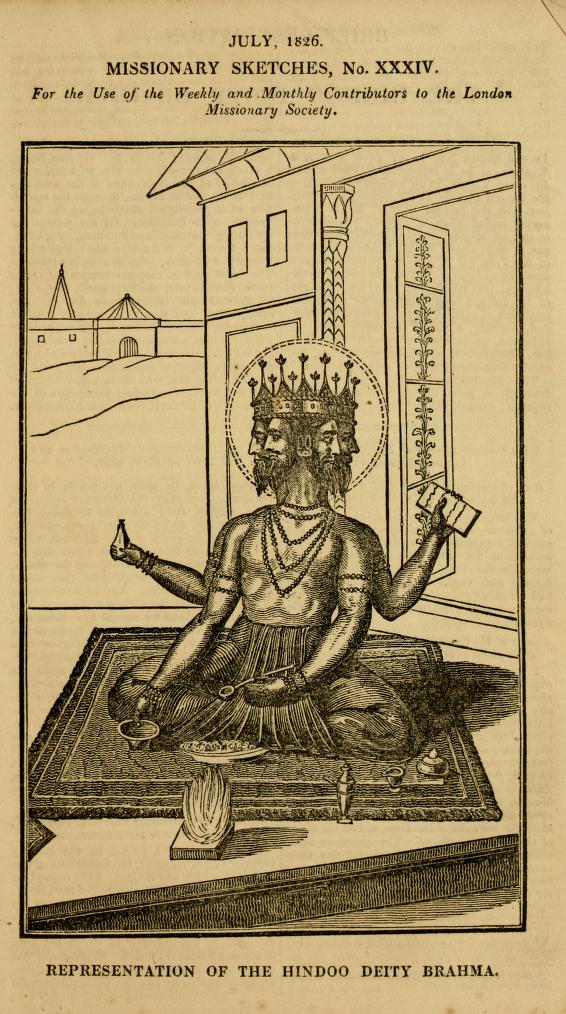

But the most valuable and impressive objects in this Collection are the numerous, and (in some instances) horrible IDOLS, which have been imported from the South Seas Islands, from India, China, and Africa; and among these, those especially which were actually given up by their former worshippers, from a full conviction of the folly and sin of idolatry – a conviction derived from the ministry of the Gospel by the Missionaries.13

Value here is accorded to ‘Idols’ over and above either Natural History or ‘efforts of natural genius’, but special emphasis is given to those given up by their former worshippers, especially when this came from ‘a full conviction of the folly and sin of idolatry’.14

For Protestant evangelicals, the removal of any ‘idols’ may have seemed a good in and of itself, but real value was connected to objects which demonstrated the purpose of the Missionary Society, as set out in its founding constitution of 1795 (Chapter 1):

The sole object is to spread the knowledge of Christ among the heathen and other unenlightened nations.15

In this light, ‘idols’ sent to the Missionary Museum by converted ‘heathen’ on the basis of conviction and a change of heart – indicators of sincere conversion – were by far the most valuable and impressive objects in the collection.

The Advertisement explicitly connects the display of these ‘singularly interesting objects’ to Pomare’s despatch of his ‘idol gods’ from Tahiti to London in 1816 (Chapter 4), quoting Pomare’s suggestion that missionaries ‘send them to Britain, that the English people might see what foolish gods they had been accustomed to adore’.16 In displaying these in their Museum, the Directors of the Society were doing no more than complying with Pomare’s wishes.

The final paragraph of the Advertisement expresses a desire that these “trophies of Christianity” will:

inspire the spectators with gratitude to God for his goodness to our native land, in favouring us so abundantly with the means of grace, and the knowledge of his salvation and at the same time, with thankfulness that these blessings have, in some happy degree, been communicated, and by our means, to the distant isles of the Southern Ocean.17

The means of grace received in the British Isles by ancestors, generations previously, was connected, as it had been at the foundation of the Society in 1795 (Chapter 1), to the forward extension and communication of these blessings to other parts of the world. The final sentence of the Advertisement, presumably originally written in 1824 suggested:

Many of the curious articles in the Collection are calculated to excite in the pious mind, feelings of deep commiseration for the hundreds of million of the human race, still the vassals of ignorance and superstition; whilst the success with which God has already crowned our labours, should act as a powerful stimulus to efforts, far more zealous than ever, for the conversion of the heathen.18

Title page for the Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars

Printed in 1826.

© British Library Board (General Reference Collection 4766.e.19.(2.)

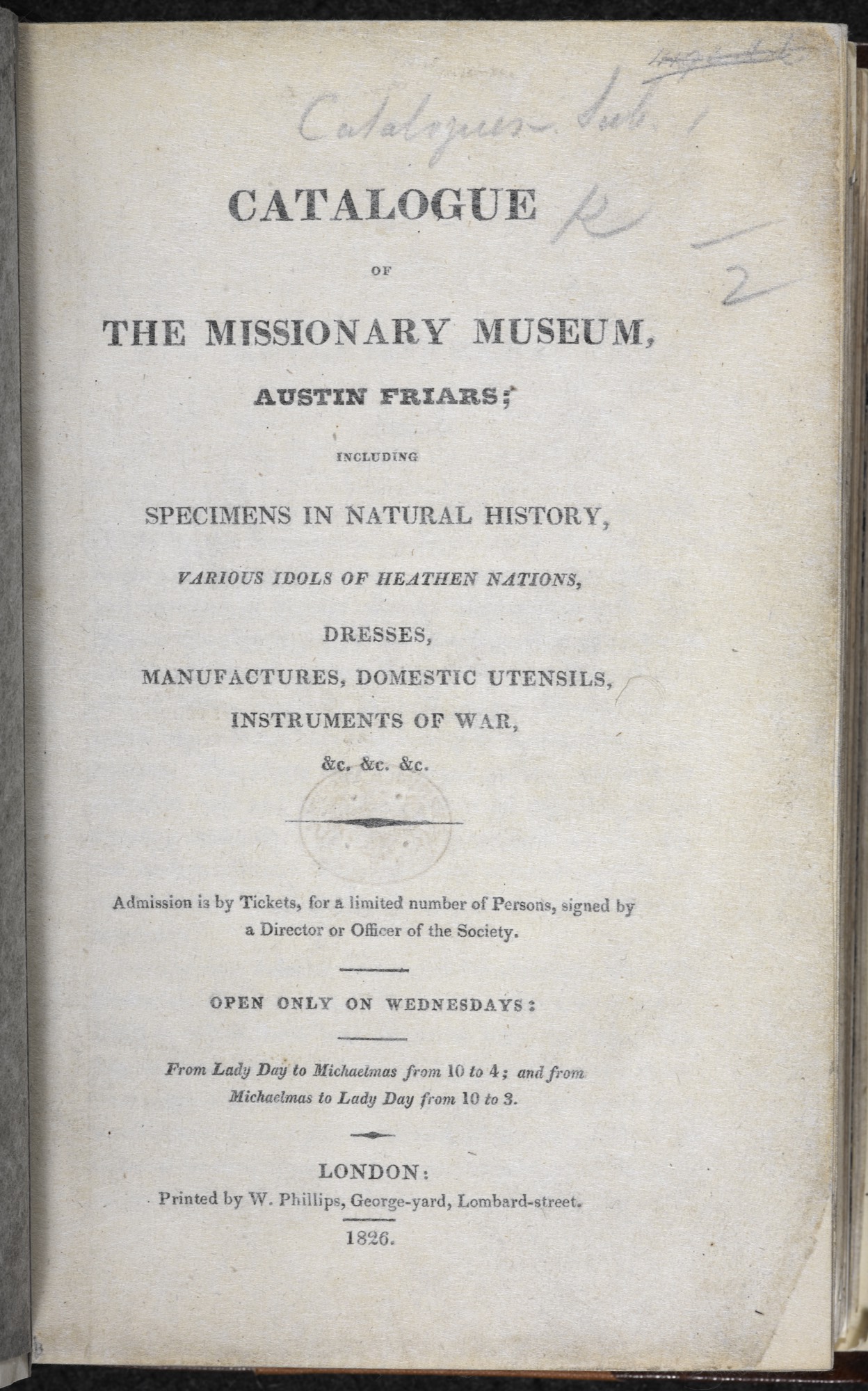

"Representations of Hindoo Idols"

Missionary Sketches, No. XIX, April 1825. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n112/mode/1up

"Representation of Lakshmi, the Celebrated Hindoo Goddess"

Missionary Sketches, No. XXX, July 1825. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n116/mode/1up

Keane’s moral narrative of modernity is briefly set out here in grand historical terms for an assumed audience of British Christians – ‘our’ ancestors were vassals of ignorance and superstition but by the grace of God ‘we’ have reached a state of liberation that creates an obligation to liberate others still bound by these same chains.

A listing of individual items forms the body of the catalogue which follows, but on the final page of the catalogue an appeal for ‘Annual Subscriptions, or Donations, in aid of the Funds of this Society’ is followed by the ‘Form of a Bequest’. This included a blank space for an amount to be entered, allowing visitors whose missionary zeal had been inspired by their visit to the museum provide a legacy for the Society.19

In 1826, the Missionary Museum was in the process of being reimagined as an extension of the fundraising work that underpinned all aspects of the London Missionary Society’s operations. The title page and Advertisement establishing a framework through which visitors would be expected to engage with the museum and its collections, categorising and valuing the materials on display, but also providing a narrative in which the visitor – assumed to be not only British, but also Protestant and most likely evangelical, or at least sympathetic – could play a part.

Prefiguring the secularised narratives of progress that would shape the museums and displays of the later nineteenth century, in relation to what Tony Bennett has called ‘the exhibitionary complex’, this script of liberating Grace has parts for missionaries, supporters, converts as well as idols.20 But how well do the artefacts listed on the pages of the catalogue play their allotted parts?

Individual scenes, including Campbell’s giraffe (Chapter 3), Pomare’s idols (Chapter 4) and Ellis’ Hawaiian bark cloth (Chapter 7) appear to conform to these categories, but taken as a whole, how far do the listings of the 1826 catalogue reflect the Advertisment’s exposition?

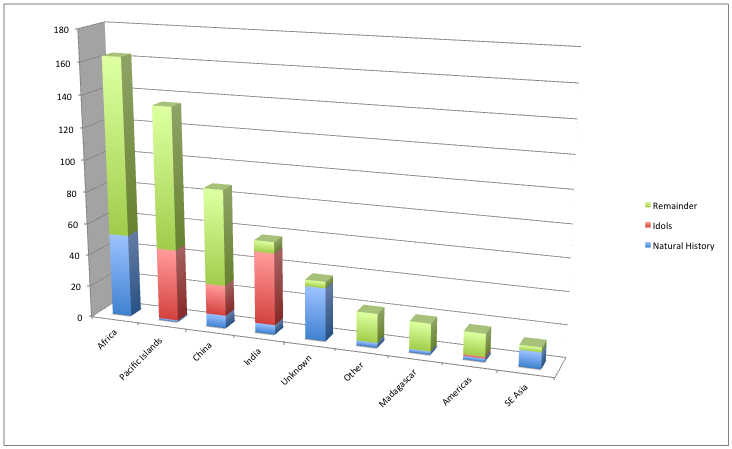

Considered in numerical terms, both ‘specimens in Natural History’ (117 listings) and ‘efforts of natural genius’ (323 listings) outnumbered ‘Idols’ (110 listings) among the 550 artefacts listed in the catalogue. Geographically, the largest number came from Africa (163 listings), with twice as many ‘efforts of natural genius’ (111 listings) as ‘specimens in Natural History’ (52 listings), but no ‘Idols’. Next came the Pacific (135 listings), with a good number of ‘Idols’ (45 listings), but still more ‘efforts of natural genius’ (89 listings). This is followed by China (87 listings), with a third as many ‘Idols’ (19 listings) as ‘efforts of natural genius’ (60 listings), although this figure includes quite a number of books (17 listings), such as the Chinese dictionary of Robert Morrison (Chapter 9).

Other geographical areas, such as Australia (Chapter 10), Madagascar (Chapter 19) and the Americas include far smaller numbers of items (107 combined total listings), but these don’t include any items that can be categorised as ‘Idols’, apart from possibly the PEHI rattle from Demerara (Chapter 5).

Only among artefacts listed as coming from the ‘East Indies’ (58 listings in total) is there a clear predominance of ‘Idols’ (45 listings). Indeed, the number of ‘Idols’ is the same as from the Pacific (45 listings), with much smaller numbers of ‘specimens in Natural History’ (6 listings) and ‘efforts of natural genius’ (7 listings). But how far do these ‘Indian idols’ represent what the ADVERTISEMENT called ’valuable and impressive objects… actually given up by their former worshippers, from a full conviction of the folly and sin of idolatry’?

Twenty-one of the forty-five ‘Idols’ listed were ‘models’, most likely commissioned by Henry Townley in Calcutta (Chapter 6). Following these in the catalogue is, intriguingly, is a listing for:

A Case of REJECTED IDOLS from Cuddapah, in the East Indies.21

John Hands began preaching and establishing schools at Cuddapah (Kadapa) in 1822, and a mission was established there by William Howell in 1824.22 It seems likely that these items were sent to London when a small number of people were baptised, according to an account published later in the century (1858) ‘from doubtful motives’.23

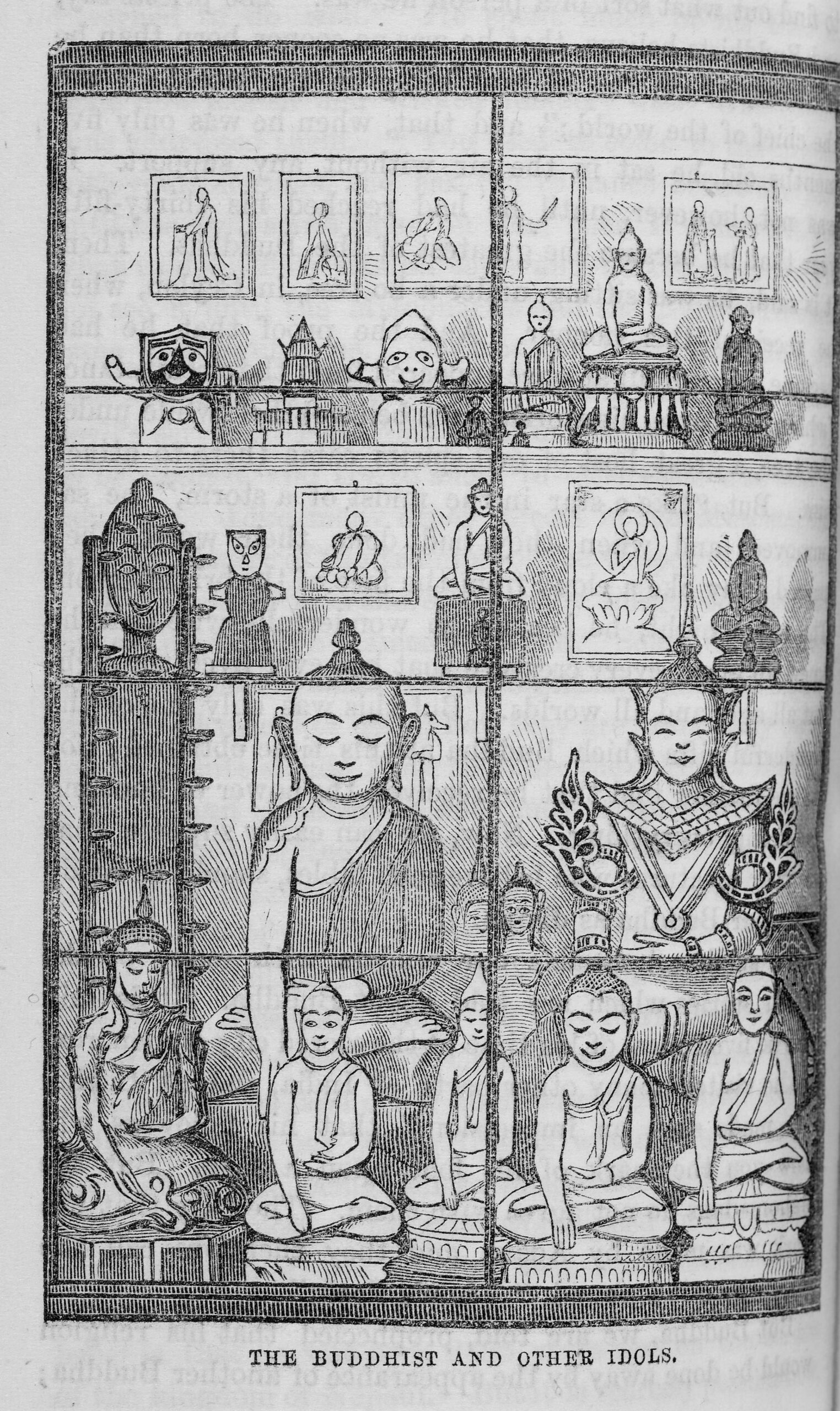

After this, the catalogue includes a fairly large number of items from Rangoon (Yangon – 19 listings), including thirteen Buddhas, two figures of Krishna, a figure of Kali standing on the stomach of Shiva, a stone lingam, and a set of bells from one of the temples. Beginning a listing for the ‘Fourth Shelf’ was a gilt Buddha from Rangoon, described as ‘a Sea Port in the Burmese Empire’.24 This was followed by a long text describing Buddha as an avatar of Vishu, taken from a Sanskrit inscription at Bodh Gaya, translated by Charles Wilkins, which appeared in the first volume of Asiatick Researches, published at Calcutta by the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1788.25

A very brief mission had been established at Rangoon in 1810, but within months one of the missionaries, J.C. Brain, had died and the other Edward Pritchett returned to Madras. Given how short this unsuccessful mission was, it seems extremely unlikely that all these items could have been collected at that time, especially as it predated the establishment of the Missionary Museum.

Rather, a hint at the likely source of these items comes from a list of thanks, published in the Missionary Chronicle of August 1826, stating:

Also, to Mr. Heritage and others of the Society’s Friends, connected with the Congregation at Union Chapel, Calcutta; for several Burmese Idols (some of which were formerly in the large Pagoda at Rangoon), and other valuable curiosities for the Society’s Museum.26

Mr Heritage appears to have been a fairly long-term resident of Calcutta, described in 1832 as the Commander of the Hon. Company’s pilot schooner “Henry Meriton”.27 This normally guided vessels on the Hooghly River, between the sea and Calcutta, making Mr Heritage what the Advertisement described as a ‘friendly officer’ of a mercantile vessel. In May 1824, however, this pilot schooner had been equipped with a pair of canons and joined the hastily assembled fleet to transport troops, together with their howitzers, to Rangoon (Yangon) as part of the first Anglo-Burmese war.28

The famous golden Shwegadon Pagoda became the military headquarters of the invading troops, who comprehensively pillaged it. It seems likely, therefore that ‘Mr. Heritage and others of the Society’s Friends’ acquired these ‘Burmese Idols’ either as a direct result of their participation in the invasion of Rangoon, or from soldiers returning from the conflict with loot.

The forced removal of these items as part of military action is not made explicit in the Missionary Museum catalogue, although the degree to which this implicit provenance would have been understood by those reading the catalogue in the years immediately after the war is unclear. From our perspective, the discrepancy between the display of these items and the ninth commandment – Thou shalt not steal – is striking, but perhaps this was felt to be balanced by the second and third commandments – Thou shalt have no other gods before me and Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image.

After the list of items taken from Rangoon, a short note in the catalogue suggests that:

In the front of the larger idols are several smaller ones, of silver, brass, copper, and stone: also a curious censer, of spoon for incense.29

These likely relate to an early arrival at the museum – back in April 1816 the Missionary Chronicle announced that Mr Hands had sent the Directors ‘a number of idols of silver, copper, &c. for their Museum. Also a copy of St. Luke’s gospel, written in leaves: Christ’s Sermon on the Mount, in the Canara language, &c.’ from Bellary [Ballari].30

John Hands began work there in 1810, where he set about translating the Bible into Canarese, so it seems likely the gospel was one on which he had worked. The first convert was only recorded in 1819, however, and the letter he sent with the items in September 1815 explained that ‘he cannot gratify them with an account of the poor Hindus around him having openly embraced the gospel’.31

With the possible exception of the ‘REJECTED IDOLS from Cuddapah’, neither the idols from Ballary, the looted material from Rangoon, nor the models from Calcutta were given up voluntarily by converts to Christianity. Nevertheless, the catalogue rounded off its listing of Indian ‘Idols’ by reprinting the text which had appeared in Missionary Sketches in 1819, following the descriptions of Townley’s ‘models’ citing Psalm cxv. 5-10: ‘These are specimens, Christian Reader, of the gods of the heathen in India worshipped by more than a hundred millions of deluded people. These are the creatures of a corrupt imagination, and the workmanship of men’s hands…’.

Following this, a paragraph from Ward’s Account of the Writings, Religion, and Manners of the Hindoos including Translations from their Principal Works was printed in the catalogue:

Nine-tenths of the whole Hindu population pay no conscientious regard whatever to the forms of their religion, and yet the various cruelties accompanying their superstitions occasion the death of more than ten thousand persons every year. And notwithstanding the veneration in which some pretend to hold their gods, yet many, especially the poor, take the liberty of abusing them. When it thunders awfully, respectable Hindoos say, “Oh! the gods are giving us a bad day;” the lower orders say, “The rascally gods are dying.” During a heavy rain, a woman of respectable class frequently says, “Let the gods perish! my clothes are all wet.” A man of low castes says, “These rascally gods are sending more rain.” Ward. vol.1 p.xc

Final page for the Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars

Printed in 1826.

© British Library Board (General Reference Collection 4766.e.19.(2.)

Bar chart showing listings in the 1826 catalogue arranged by geographical region, with categorisation by colour.

Red shows ‘Idols’, dominating the Indian collections in particular, Blue shows ‘Natural History’ while ‘Green’ shows everything else (efforts of natural genius)

Bar chart showing listings in the 1826 catalogue arranged by geographical region, with further categorisation by colour.

Here Green shows ‘Natural History’ and Red shows ‘Idols’ but other colours are allocated to the other categories listed on the Catalogue’s title page (Dresses, Manufactures & Domestic Utensils, Instruments of War), while an additional category has been added for ‘Publications’, which demonstrates how significant these were as part of the collection from China.

"The Buddhist and Other Idols"

Published in ‘The Missionary Museum No. XI’. 1861. Juvenile Missionary Magazine, 18, p.60, Author’s Personal Collection.

"Scene upon the Terrace of the Great Dagon Pagoda."

Watercolour by Lieutenant Joseph Moore, made during the British occupation of Rangoon, and published in 1826.

Library of Congress (Public Domain): 2021670151

"Representation of the Hindoo Idol Surya, or the Sun."

Image depicting a cast at the East India Company Museum, made by ‘Mr Wilson’ at the Temple of Shiva at Benares.

Missionary Sketches, No. XXXII, January 1825. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n124/mode/1up

Two lines, one thick, mark an ending of sorts for the ‘EAST INDIES’ section of the Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, but in the remaining space of the page follows the description with which this chapter began:

THE VIRGIN MARY AND CHILD, from Mysore, that belonged to two Native Roman Catholics, who embraced the Christian religion, and sent the same to the Missionary Society

Beneath this a further paragraph appears in quotation marks:

“The people were in great consternation at the removal of the image, and offered large sums of money for it; one offered twenty pagodas, another his daughter, and another even declared he would sell his own child and procure money enough to purchase it, if it might be retained; but a deaf ear was turned to the proposals, being aware of the danger of making it an object of worship, and felt as the disciples of Christ,- constrained to take it away.” Vide Missionary Chronicle for January 182632

Description from the Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars

Printed in 1826 (p. 31)

© British Library Board (General Reference Collection 4766.e.19.(2.)

Given that the publication referred to appeared in the same year as the Catalogue was printed, I initially wondered whether the inclusion of this text after the thick black line suggested an addition to an already prepared printing block. However, given that the items from Rangoon were reported even later in the same year (August), but were incorporated into the main section of the East Indies section, I now think that the lines serve to deliberately demarcate a Christian ‘idol’ from the ‘heathen’ idols that preceded it.

The paragraph in quotes comes from a printed version of a letter, originally sent to the Society’s secretary on 23 July 1825 and signed by the London Missionary Society’s three European missionaries at Bangalore, Hiram Chambers, William Campbell and Stephen Laidler. It explained:

We are permitted at this time to lay before you, two trophies of the victorious power of divine truth over the delusions of the Antichrist; trophies which we hope and trust may prove powerful auxiliaries in making known Christ and Him crucified, to their perishing fellow-men.33

The Antichrist was not a gruesome Heathen deity, but rather the Catholic Church, and the two ‘trophies’ were not ‘idols’, but rather two young men who had converted to Protestant Christianity and who, it was hoped, would play a part in converting others. Christianity’s roots in south India are believed to go back to the arrival of St Thomas the apostle in the first century, but the roots of Catholicism in Mysore are generally traced to the establishment of a Mysore mission by Father Leonardo Cinnami in 1649.

Following a visit to Bangalore (Bengaluru) by John Hands, from his mission station at Bellary (Ballard), 300km away, Stephen Laidler had established a mission there for the LMS in 1820. With access to the Indian town prohibited to European missionaries by the Rajah of Mysore, preaching was initially directed at the Europeans and Sepoys in the military cantonment. This seems to have changed, however, after the arrival at the mission of Samuel Flavel, who actively preached in surrounding villages, distributing tracts and copies of the gospels in local languages.34

Born at Quilon (Kollam) on the Malabar Coast of Kerala in 1787, Shunkurulingam, as he was known before he was baptised, was employed by a British officer at a fairly young age. He travelled widely in India, visiting Mauritius before being employed in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) as a butler. He came across a translation of the Gospels into Tamil which initiated a personal quest to know more about Protestant Christianity. This led to his baptism at Tellicherry (Thalassery) by an East India Company chaplain, when he adopted the name Samuel. Invited by Laidler to join the new mission at Bangalore, Samuel became central to its work. He was ordained as the pastor of the native church in 1822, when he adopted the surname Flavel at Laidler’s suggestion. John Flavel, like his Indian namesake, had been a learned Puritan minister, famous for preaching in the face of official prohibition.

The letter, written at Bangalore in July 1825, and printed in the Missionary Chronicle in January 1826, concerns an event that took place in the city of Mysore (Mysuru), with none of the three European missionaries present. Samuel Flavel had made the journey of nearly 150km at the invitation of two brothers who were catechists at the city’s Roman Catholic Church.

Five years previously they had talked with Joshua, an Indian convert connected to the London Missionary Society, which led them to question Catholic practice. The elder of the two was, according to the account given, flogged by the priest for his impertinence – an example of what the letter refers to ‘the carnal weapons of Antichrist’.35

"Representations of Hindoo Deity Brahma"

Missionary Sketches, No. XXXIV, July 1826. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n132/mode/1up

Visited in April 1824 by another Indian convert, John, who had recently been baptised at Bangalore, the elder brother wrote to Flavel, asking for a meeting. Flavel told the European missionaries that when he arrived in Mysore, the Catholic congregation had been commanded by the priest not to speak to him, who described him as ‘the greatest devil he had known among the Protestants’.36

The congregation reportedly tried to persuade the two brothers, whose father had been a Catholic, not to leave the church, offering to double their allowance as catechists. Unpersuaded, the letter suggests they were ‘treated with great contempt and abuse’, and given a kicking, which was ‘received as became the disciples of the meek and lowly Jesus’, praying for their attackers. The younger brother was accused by the crowd of saying they were the “Antichrist”, to which he replied that beating and flogging the pair received ‘fully proved that they deserved that name.’37

The brothers then went to the Catholic Church ‘with a view to removing some images which were their private property, and which had formerly belonged to their father’, destroying all except that of the Virgin Mary.

This had been embellished with jewels by ‘infatuated devotees’, especially one woman who believed Mary ‘had been propitious to her’. The congregation claimed the jewels as the property of the church, attempting to persuade the brothers to accept payment for statue, arguing that ‘if it were taken away, some curse would descend upon the congregation’ – some of the details of their offers were summarised in the paragraph that was quoted in the catalogue of the Missionary Museum.

Turning a deaf ear, however, they:

endeavoured to demonstrate with the poor infatuated people, showing the folly and sin of these offers, assuring them that they did not refuse their offers because the expected more money for it; but being aware of the danger of making it an object of worship, they felt, as the disciples of Christ, constrained to take it away.38

When they did so they were charged with further debts which were subsequently dismissed by a magistrate. Baptised by Samuel Flavel, they took the names Nathaniel39 and Jonas and travelled with him to Bangalore, presumably taking the statue of the Virgin Mary and infant Jesus with them.

According to the letter signed by the three European missionaries, this was:

the plain unvarnished tale of the conversion of these two men from the errors and superstitions of the Church of Rome, to the profession of the truth as it is in Jesus.40

Indian Madonna and Child

17th – 18th century Indo-Portuguese Ivory of the kind likely to have been located in the Roman Catholic Church at Mysore in 1825.

Minneapolis Institute of Art (CC BY 4.0): 2019.10.10

Here, at last, was an ‘idol’ unambiguously ‘given up by former worshippers, from a full conviction of the folly and sin of idolatry’ in the East Indies section of the catalogue of the Missionary Museum. Rather than being a Hindu murti or Buddharūpa, however, it was an image of the Virgin Mary. It may have been given up through ‘a conviction derived from the ministry of the Gospel by the Missionaries’ although these Missionaries were not Europeans, but fairly recent Indian converts.

The following month, in February 1826, the editors of the Missionary Chronicle returned to the Bangalore mission, printing another letter from the same three missionaries sent slightly earlier, on 15 May 1825. This described an encounter between Samuel Flavel and an Indian Catholic from Madras. Evidently ‘all that Samuel said was well received, till he spoke against praying to the Virgin Mary and departed saints’. The two men agreed to have a public disputation in the bazar, for which Samuel proposed four questions:

- Is the faith of the Roman Catholic church the faith of the church of Christ?

- Is the church of Rome the church of Christ?

- Are its ceremonies, – such as bowing to the priests with their faces to the ground, counting their beads, and wearing crosses round their necks, the ceremonies of the church of Christ?

- Are its acts of worship,- such as bowing to images, ringing of bells, &c. – lawful in the church of Christ?41

Their conversations were evidently attended by sixty or seventy people, many of whom are referred to as ‘heathens’, and their meetings continued over more than a fortnight. According to the letter, the seriousness with which these events were approached made the European missionaries at Bangalore think:

of the contests which, in the days of Luther and of Calvin, produced such effects in the western world; and we rejoiced in the hope that this might prove a commencement of the more certain and speedy overthrow of Antichrist in this distant land.42

In the translation and summary of the dialogue that was printed, the disputation centred on the accuracy of the translation of the second commandment, relating to graven images, with Flavel exclaiming that:

I believe, then, that Jesus Christ is the Son of God; that he is the only Mediator between God and Man; that he is the way, the truth, and the life; that he is able to save to the uttermost all that come unto God by him; and that he is the only Advocate who intercedes for us at the right hand of his Father.43

When challenged on the difference between worshiping and looking at images, Flavel’s Catholic interlocutor suggested that Protestant bibles also included pictures of Jesus Christ. Flavel’s counter was to volunteer to burn these images and say he rejected them if his interlocutor was prepared to do the same for Catholic images.

The letter ends its account of the dialogue by stating that it was an imperfect translation ‘as Samuel speaks his own language not only very correctly, but often with elegance and eloquence’ – revealing the severe linguistic limitations that held back the preaching efforts of European missionaries in other parts of the world.44

It is significant that both letters sent from Bangalore in 1825 end by outlining plans for Mysore College, a seminary that was intended to bring ‘forward pious native youth for the ministry of the gospel’.45 The degree to which the London Missionary Society would support and embrace local Christian teachers, such as Samuel Flavel, would become a defining question for the Directors of the London Missionary Society, back in London.46

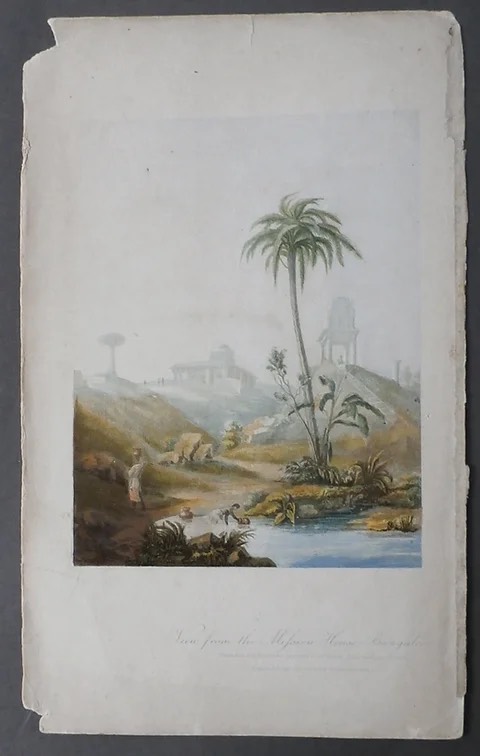

"View from the Mission House, Bangalore"

Printed in Oil Colours by G. Baxter (Patentee), 3 Charterhouse Square, London.

Published as the frontispiece to William Campbell’s British India, 1839

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this chapter appeared in the Südasien-Chronik – South Asia Chronicle, together with Chapter 6, under the title ‘South Asian Artefactual Histories from the London Misisonary Society Museum, 1814-1826’. I am very grateful to Tobias Delfs for the invitation to contribute to the special issue of the journal on Christian mission in South Asia.

As someone who is not a specialist on South Asia, I have been cautious venturing into this field, but in writing these artefactual histories I realised I had probably learnt more from tutorials in Oxford with Nicholas Allen and Clare Harris, as well as lectures by Richard Gombrich, than I had remembered. I am grateful for my education in South Asian religion and would like to mark Nick’s passing in 2020.

Notes

1 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.), p.31

2 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.), p.23

3 Keane, W. 2007. Christian Moderns: freedom and fetish in the mission encounter, Anthropology of Christianity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

4 London Missonary Society. Thirtieth Report. Missionary Register, October 1824, p.425: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5MYnAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=London%20MIssionary%20Society%20Register%201824&pg=PA425#v=onepage&q&f=false; The following year, a further £711,11,6 was recorded against ‘Repairs, &c for Mission House, furnishing and fitting p the Museum, together with Freight and Charges upon Idols and other Curiosities exhibited therein. Disbursements, The Report of the Directors. 1825/ P. Lxxxv (p.261) : https://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001298/00003/275?search=museum

5 South Seas. Missionary Chronicle for October 1824. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1824, vol. 2, pp. 457: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=kM1GAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20mission%20ary%20chronicle&pg=PA457#v=onepage&q&f=false

6 The Missionary Museum. The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for July 1824, p.333: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=kM1GAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20mission%20ary%20chronicle&pg=PA333#v=onepage&q&f=false

7 The Missionary Museum. The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for August 1824, p.365: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=kM1GAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20mission%20ary%20chronicle&pg=PA365#v=onepage&q&f=false

8 With an equivalent 2022 purchasing power of £5000: https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/ukcompare/relativevalue.php; Missionary Boxes. Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for May 1825, p. 214: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=2t86AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA214#v=onepage&q&f=false.

9 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.).

10 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iii

11 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iii

12 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iii

13 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iii

14 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iii

15 Lovett, R. 1899. The History of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895. London; Henry Frowde. Vol. 1, p. 30

16 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iv

17 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iv

18 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. iv

19 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. 47

20 Bennett, T. 1988. The Exhibitionary Complex. new formations, 4, 73-102: https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/newformations/vol-1988-issue-4/abstract-7713/

21 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. 28

22 Cuddapah. Missionary Chronicle for July 1825. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1825, vol. 3, pp. 308-9.

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=2t86AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA308#v=onepage&q&f=false.

23 Porter, E. 1858. Telugu Missions, The Cuddapah Mission of the London Missionary Society. Proceedings of the South India Missionary Conference, vol. 4, pp. 116: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=3P4CAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=Cuddapah%2C%20where%2020%20families%20of%20Malas%2C%20abandoning%20their%20idols%2C&pg=PA116#v=onepage&q&f=false.

24 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. 29

25 XI. Translation of a Sanscrit Inscription, copied from a stone at Booddha-Gaya, by Mr Wilmot, 1785. – Transalted by Charlies Wilkins, Esq. in Asiatick Researches: or Transaction of the society instituted in Bengal for inquiring into the History and Antiques, the Arts, Sciences and Literature of Asia. Volume the First. Calcutta, 1788, p.284: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=AyhFAAAAcAAJ&vq=284&pg=PA284#v=onepage&q&f=false

26 Missionary Contributions for August 1826. Missionary Chronicle for August 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 367-8: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA366-IA2#v=onepage&q&f=false.

27 Biography: Rev. J.D. Pearson of Chinsurah. Missionary Register. August 1832, p. 326: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=DkUUAAAAYAAJ&vq=meriton&pg=PA326#v=onepage&q&f=false VETC.

28 Edwardes, H.B. and H. Merivale. 1872. Life of Sir Henry Lawrence, 2 vols. London: Smith, Elder & Co. P.52 : https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=FwFLAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=henry%20meriton%20pilot%20schooner&pg=PA53#v=onepage&q&f=false; Sridharan, K. 1982. A Maritime History of India. Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, New Delhi, p. 134: https://archive.org/stream/in.ernet.dli.2015.132162/2015.132162.A-Martime-History-Of-India_djvu.txt

29 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. 31

30 Bellary. Missionary Chronicle for April 1816, In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1816, vol. 24, pp.155-6; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ofI6AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201816&pg=PA155#v=onepage&q&f=false.

31 Bellary. Missionary Chronicle for April 1816, In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1816, vol. 24, p. 155; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ofI6AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201816&pg=PA155#v=onepage&q&f=false.

32 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friars. 1826. London: Printed by W. Phillips. British Library 4766.e.19.(2.). p. 31

33 East Indies: Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for January 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 32-3: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false.

34 Lovett, R. 1899. The History of the London Missionary Society, 1795-1895. London; Henry Frowde. Vol. 2, pp. 104-105

35 East Indies: Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for January 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 32: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false.

36 East Indies: Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for January 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 32: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false.

37 East Indies: Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for January 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 32: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false.

38 East Indies: Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for January 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 33: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false.

39 According to the King James Bible John 1:47, Jesus said of Nathaniel “Behold, an Israeli indeed, in whom is no guile!”.

40 East Indies: Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for January 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 33: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false.

41 Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for February 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 77-83: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionar%20y%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA77#v=onepage&q&f=false

42 Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for February 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 77: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionar%20y%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA77#v=onepage&q&f=false

43 Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for February 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 78: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionar%20y%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA77#v=onepage&q&f=false

44 Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for February 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 80: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionar%20y%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA77#v=onepage&q&f=false

45 East Indies: Bangalore. Missionary Chronicle for January 1826. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1826, vol. 4, pp. 33. https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=IPIDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20museum%20and%20missionary%20chronicle%201825&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false.

46 In 1827 Stephen Laidler resigned as a missionary. Samuel Flavel moved to the mission at Bellary (Ballari), where he continued to preach for the next twenty years. James Ashton, as the younger of the two converted brothers was known after baptism, became a school teacher at the LMS mission at Belgaum (Belagavi): Belgaum. James Ashton, the Native Reader. The Missionary Magazine and Chronicle for March 1837. In: The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle 1837, vol. 15, pp. 144-5: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=zfUDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA144#v=onepage&q&f=false.