New London Bridge, 11 April 1838

When the City of Canterbury, a paddle steamer carrying around four hundred friends of the London Missionary Society, pulled away from New London Bridge, John Williams waved to the crowd gathered on the bridge and surrounding wharfs. The ‘multitudes who had assembled to witness their departure, and to testify their interest in the important enterprise’ cheered in response, ‘the ladies waving their handkerchiefs’.1

Since his return to London in a whaling ship in June 1834, Williams had toured the country, speaking to missionary meetings about his eighteen years in the Pacific. His Narrative of Missionary Enterprises in the South Sea Islands, describing events including the conversions of Rurutu, Rarotonga and Aitutaki (Chapter 12), had been a sensation following its publication a year earlier.

When it became clear, in December 1837, that the Government would not provide Williams with a ship, he set about raising the necessary funds himself. By January, there was enough to purchase the Camden, a 200 ton, eighteen year old former postal vessel. By the end of March, the Camden had been repaired and fitted up by Fletcher’s boatyard in Poplar, without charge, with a total of £4000 raised in support. This included £500 from the Court of Common Council of the City of London, on the grounds that Missionary work opened the way to British commerce.

John Williams was the man of the moment and his departure seemed to mark an opening into history. As a new Queen, Victoria, awaited her coronation (on 28 June), the proliferation of steamships and railways across the Kingdom had raised British confidence to new heights. Williams’ biographer and friend, Ebenezer Prout, remembered five years later that:

To the eye of hope, the future was as bright as the present; not a cloud darkened the horizon, and all seemed to anticipate the day when they would hear of fresh triumphs which he would be honoured to win for the truth and grace of the Lord Jesus.2

The Departure of the Camden, Missionary Ship

April 11, 1838 with the Rev. John Williams and missionaries for the South Seas, from the River Thames, sketched on the spot and printed in oil colours by G. Baxter, patentee

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK352.

George Baxter, who had illustrated Williams’ book, was waiting to document the moment the Camden set sail. Three years earlier he had patented a new technique for printing colour images, used for the frontispiece in Williams’ book, which showed ‘Te Po, a Chief of Rarotonga’ (Chapter 12), at least in the early editions. When John Snow, the publisher, found he could sell the portrait of John Williams that replaced this in later editions independently, he encouraged Baxter to try something new.3

As the paddle steamer approached the Camden, anchored at Gravesend in Kent, the passengers gathered on deck to sing hymns, written for the occasion. They lowered their eyes for prayers, offered by the Rev. T. Jackson, the only surviving Director of the Society who had witnessed the departure of the Duff, just over four decades earlier (Chapter 1).4

Ten missionaries, eight missionary wives, as well as the eldest son of John Williams together with his new wife transferred to the Camden, and Baxter sketched the moment the final sail unfurled as the Camden began to move, water lapping at her bow. For around ten miles, the City of Canterbury continued beside the Camden, allowing him time to finish the sketch, including details of the fully laden ship, with three flags flying from her masts.

That on the fore-mast carried the Society’s emblem – a dove with a green sprig in its beak and that at the stern features the word ‘Bethel’, ‘house of God’ in Hebrew, the name given by Jacob to the place he dreamed of a stairway stretching between Heaven and Earth.5

Atop the main-mast, the highest point of the ship, the words on the flag are harder to make out, partly because they are reversed in the colour image and partly because they are not English words. The ‘Ladies of Rev. W. Woodhouse’s congregation, Swansea’ had made a flag for the Camden with the Welsh inscription Cenad Hedd, meaning ‘Messenger of Peace’.6

Baxter worked quickly, turning his sketch into an engraving for the cover of the following month’s Missionary Magazine. It was also used on the title page of The Missionary’s Farewell; Valedictory Services of the Rev. John Williams, previous to his Departure for the South Seas, bringing together the speeches and hymns, with an account of the events of the day.

There the image of the Camden was printed above a caption ‘And they accompanied him unto the ship’, a quotation from the Acts of the Apostles (20:38), in which Paul addressed the Ephesians at Miletus, since they ‘would see his face no more’. Reviewers of Williams’ book had similarly connected it to the New Testament, declaring it to be a ‘a history of Gospel propagation, unequalled by any similar narrative since the Acts of the Apostles’.7

In Farewell to Viriamu (the Tahitian version of Williams’ name), a booklet given to those on the City of Canterbury, the first hymn referred to Williams as ‘APOSTLE OF THE ISLES’.8 The text which followed Baxter’s engraving in the May 1838 Missionary Magazine declared the significance of his departure in national rather than biblical terms:

England stands pre-eminent among the nations of the earth as a maritime power… But never, since the departure of the Duff, has a vessel left our shores under circumstances and for objects entirely similar to those which have marked the departure of the Camden.9

If John Williams was a living Apostle, following a path set by St. Paul, his departure in the Camden demanded commemoration. Working with John Snow, the publisher of Missionary Enterprises, who, together with Prout, remained with Williams on the Camden until it left English waters a week later, Baxter created a colour print to be sold in its own right.10 Adverts at the front of Snow’s publications listed this alongside his books as follows:

Dedicated to the London Missionary Society, price 4s.

A SPLENDID COLOURED PRINT,

Representing the Departure of the CAMDEN Missionary Ship, with the Rev. J. WILLIAMS and Missionaries for the South Seas, from the River Thames; sketched on the spot, and printed in Oil Colours by G. BAXTER, Patentee. Size of Print, including tinted board, 10 inches by 14 inches.11

The board on which the print was mounted included many of the same details, as well as a title in bold letters, The Departure of the Camden, Missionary Ship, the title of this chapter.

In creating the colour image, Baxter added the City of Canterbury to the right of the Camden, its smoke blowing with the wind.12 Comparing the colour image to its black and white precursors suggests that Baxter also added the boats in the foreground, filled with supporters waving hats and handkerchiefs. The way the departing ship is framed by these appears to suggest the Camden’s sails were filled with their cheers, and no doubt prayers, of supporters across the British Isles.

For John Williams, the departure of the Camden marked just the latest in a series of ambitious maritime voyages. Having regarded the forced sale of the Endeavour in 1823 as a victory for Satan (Chapter 12), when left without a ship at Rarotonga in May 1827, he decided to improvise.13

Williams began a ship building project soon after he returned to Avarua in July 1827, with the support and assistance of the local ruler, Makea Pori. This must have strained locally available resources, unfolding in parallel to church building projects (Chapter 12), suggesting it was also important to Makea.14

When a European ship finally arrived at the island in November 1827, Williams wrote to William Ellis in London, telling him about their efforts:

She is built entirely of tamanu, and about fifty or sixty tons, quite sharp. We have been three months about her, and intend to launch her next week, and start for Raiatea. I call her “The Messenger of Peace”. My first projected voyage is to take not less than twelve native teachers to different islands, go to the New Hebrides, New Caledonia, &c. If you can incline the Directors to give me copper for her, I shall be obliged.15

In his Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, Williams described the construction of the two masted schooner, improvising a set of bellows, cutting trees with locally made adzes, and using locally made bark cloth to fill gaps between the planks. Rope was made from hibiscus and sails from sleeping mats. According to Ebenezer Prout, who edited the book:

It has been frequently said that his own “Narrative of Missionary Enterprises,” is invested with all the romantic interest which belongs to the fictitious “Adventures of Robinson Crusoe,” with the additional power derived from its truth. But it must be confessed that the portion of this work which describes the building of his ship, possesses a fascination altogether peculiar… Defoe never ascribed to the hero of his romance any achievement so wonderful.16

We should remember, however, that while Robinson Crusoe only had “Man Friday” to help him, Williams use of the pronoun ‘we’ included hundreds of experienced Rarotongan canoe builders.17

The first attempt to sail the Messenger of Peace resulted in a broken foremast, but after repairs were made, her first voyage was to Aitutaki, 170 miles away, accompanied by ‘the king, Makea’.18 Like Kamehameha in Hawai’i (Chapter 7), Makea seems to have immediately grasped how such a vessel could extend his exchange relationships and enhance his status.

The Messenger of Peace returned to Rarotonga with a cargo of pigs, coconuts and cats (Rarotonga having been overrun by rats), as well as ‘a considerable quantity of native cloth and mats, which are highly esteemed, and of considerable value at Rarotonga’, obtained by Makea at Aitutaki.19

Shortly after their return to Rarotonga, a new missionary, Aaron Buzacott, arrived, bringing with him iron to strengthen the ship. He also brought letters from Ra’iatea, telling Williams that Tuahine, the Tahitian deacon he had left in charge, one of the earliest converts at Tahiti who had assisted Henry Nott to translate the bible into Tahitian, had died.

Stopping at Papeete harbour at Tahiti, the Messenger of Peace sailed to Raiatea, arriving on 26 April 1828, in time for the annual missionary meeting. Makea, who joined the voyage, oversaw ‘the exhibition of the rejected idols of his people’.20 He then spent two months visiting the important men on the islands of Raiatea, Tahaa and Borabora, with whom he exchanged gifts.

Despite Makea’s obvious investment in the Messenger of Peace, John Williams’ Narrative of Missionary Enterprises established the archetype of the shipbuilding missionary, seemingly able to conjure up a vessel with his own bare hands – an association that endured for over a century (Chapter 23).21

From Ra’iatea, the Messenger of Peace delivered Polynesian missionaries to the Marquesas Islands and on her return was fitted with further ironwork, sent by congregations in Birmingham. She was also painted with green paint supplied by the captain of the Seringapatam, a visiting British naval frigate.22

In May 1830, the Messenger of Peace embarked on another journey, to what, at the time, were called the Navigators Islands (now the Samoan Islands), stopping in the Cook Islands, where an epidemic was raging. Williams described leaving Aitutaki with ‘ten native Missionaries’ on board, and hoisting ‘our beautiful flag, whose dove and olive-branch were emblematical both of our name and object’ – a note in Williams’ book acknowledging the flag had been made and sent to the Pacific ’by some kind ladies at Brighton… with the work of their own hands’.23

Stopping at Niue, where they attempted to leave teachers from Aitutaki, an older man came aboard, but when Polynesian evangelists attempted to cover his nakedness, wrapping a piece of bark cloth around his body, he tore it off, exclaiming:

Am I a woman, that I should be encumbered with that stuff?24

From Niue, they sailed to Tonga, where Wesleyan missionaries had been working since 1826. During a visit to their mission at Nuku’alofa, it was agreed that Fiji, with its political connections to Tonga, should become a province of the Wesleyan mission.25 Travelling to Vava’u,and Ha’apai with the Wesleyans, Williams was shown a marae where five ‘gods, disrobed of their apparel’ were ‘hanging in degradation like so many condemned criminals’. He asked to be given one of these, which he took to England ‘with the very string around its neck by which it was hung’, where George Baxter used it to make an illustration for his book.26

At Nuku’alofa, they also met Fauea, a high status Samoan man who had been at Tonga eleven years, who promised to make the necessary introductions if they took him and his wife back to Samoa. As a result, they were warmly received at Savai’i in August 1830. Presents were exchanged with Mālietoa Vainu‘upo and his brother Taimalelagi who were in the ascendent, including:

one red and one white shirt, six or eight yards of English print, three axes, three hatchets, a few strings of sky blue-bead, some knives, two or three pairs of scissors, a few small looking-glasses, hammers, chisels, gimlets, fish-hooks, and some nails.27

Leaving Polynesian missionaries at Samoa, the Messenger of Peace sailed to Raiatea, before returning to Rarotonga in September 1831. There the vessel was repaired and lengthened by Makea while Williams worked on translating the gospel into Rarotongan. While there, an extremely destructive hurricane drove the Messenger of Peace onto the shore, and although she survived, seventy sheets of copper were lost. Williams was able to distribute tools, sent by supporters in Birmingham, to assist the reconstruction effort following the storm.

The Messenger of Peace was not relaunched until May 1832, when two thousand Rarotongans pulled her back to the sea. Returning to Raiatea, Williams was ’perfectly astounded at beholding the scenes of drunkenness which prevailed in my formerly flourishing station’, where many had abandoned the mission during his absence.28 A war against ‘ardent spirits’ was launched, but Williams soon felt the call to return to Samoa.

Taking flour, horses, donkeys and cattle to missionaries at Rarotonga en route, the Messenger of Peace set off for Samoa in October 1832 with Te-ava, a Rarotongan who had volunteered for missionary service. Visiting a number of Samoan islands, Williams heard many had already abandoned their old practices and were awaiting the arrival of missionaries. Commenting on the difficulty of meeting such demand, Williams suggested in his Narrative of Missionary Enterprises:

I trust that the day is not distant when Missionaries will not be doled out as they now are, but when their numbers will bear a nearer proportion to the wants of the heathen. And why should not this be the case? How many thousands of ships has England sent to foreign countries to spread devastation and death? The money expended in building, equipping and supporting one of these, would be sufficient, with Divine blessing, to convey Christianity, with all its domestic comforts, its civilising effects and spiritual advantages, to hundred and thousands of people.29

An appeal for British missionaries for Samoa, where Polynesian evangelists were already at work, became the central focus for the final chapters of Williams’ book. As at other islands in the Pacific, the initial focus for evangelisation was on the overthrow of existing practices, but those in Samoa seemed to be different to the Society and Cook Islands.

John Williams was told by evangelists about the ‘destruction of Papo… the god of war, and always attached to the canoe of their leader when they went forth to battle’. However, Papo was ‘nothing more than a piece of old rotten matting, about three yards long, and four inches in width’. Although burning was first proposed, new converts agreed that Papo should rather be drowned, since drowning was a less horrific death.30

Fauea, who had taken Williams to Samoa, was supposed to tie a stone to Papo before the drowning, but Polynesian teachers intervened, asking that Papo be given to them, so that they could present it to Williams, who according to his book,‘placed it in the Missionary Museum’.31

Beyond this ‘god of war’, Williams suggested that Samoans ‘generally have no idols to destroy’.32 The Chiefs were nevertheless persuaded to break their taboos by consuming their etu, the bird, fish or reptile to which they were spiritually bound. Williams suggested that ‘like the ancient Miletans’ they expected to die as a consequence, but when no harm came to them, acknowledged ‘that Jehovah was the true God’.33

On the way back to Rarotonga, having rescued the wife of Puna, the evangelist to Rurutu (Chapter 12), who had been marooned at Niuatoputapu attempting to return to Ra’iatea, the Messenger of Peace suddenly filled with water. Assisted by Samuel Henry and the crew of the English whaler Elizabeth, who happened to be at Tonga, the source of the leak was discovered – a hole in the keel which had been filled with mud and stones during the hurricane.

After several months at Rarotonga in early 1833, where Williams continued working on translating the New Testament alongside other missionaries, he returned to Tahiti in July 1833. Meeting a weaver, sent from London by the Directors, Williams delivered him to Rarotonga before returning to Ra’iatea. When a British whaling ship, Sir Andrew Hammond, arrived at the island, ready to make a return journey, Williams, his wife and three children took berths on board, sailing via Cape Horn.

The Messenger of Peace, as she appeared when leaving Rarotonga for Tahiti

Illustration by George Baxter from John Williams (1837) Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, p.165

'Makea, King of Rarotonga' (ariki of Te Au O Tonga vaka)

Part of a collection of 30 large watercolours used on lecture tours in Britain by John Williams during the 1834 and 1837.

National Library of Australia, Rex Nan Kivell Collection NK1224/6

The Messenger of Peace, as she appeared when leaving Rarotonga for Tahiti

Illustration by George Baxter from John Williams (1837) Narrative of Missionary Enterprises,opposite p.293

One of five 'gods disrobed of their apparel' seen at Vava'u

Illustration by George Baxter from John Williams (1837) Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, p.321

The Interview at Leone Bay on the south coast of Tutuila

As the crew and Williams prayed befe landing, Amoano, the chief, ‘waded into the water nearly up to his neck, and took hold of the boat, when, addressing me in his native tongue, he said, “Son, will you not come on shore?”. When told of two boats taken earlier, according to Williams, he said “Oh, we are not savage now; we are Christians.” Those who identified as Christians had tied a piece of white bark cloth around his arm.

Illustration by George Baxter from John Williams (1837) Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, opposite p. 417

The Messenger of Peace, under repair at Tonga

Illustration by George Baxter from John Williams (1837) Narrative of Missionary Enterprises, p.473

Arriving in Britain on 11 June 1834, nearly eighteen years after they had left at the age of twenty, John and Mary Williams discovered a metropolis transforming almost as fast as the Pacific islands they had left. One significant change, after nearly four decades of London Missionary Society operations, was the increased number of people in Britain with experience of overseas postings.

William Ellis had been Foreign Secretary since 1832 (Chapter 13), Martha Mault had been promoting female education since the previous September (Chapter 14), while other former missionaries, such as Henry Townley (Chapter 6), had returned from India to lead British churches.

When the income of the Society had fallen off rapidly from a peak in 1830, the Directors recognised the potential for missionary speakers to inspire donations. In early 1833, Richard Knill had been invited by William Ellis to return from St Petersburg in Russia to ‘promote the interest of the Society’ , not only among existing auxiliaries:

but also to organise new societies, wherever practicable, and thus bring under contribution several extensive districts, which are at present yielding very inadequate pecuniary aid towards the great object of evangelising the world.34

With the abolition of slavery in British colonies approaching in August 1834, Knill’s fundraising had focussed on establishing missions among those who would soon be emancipated. The close links between Missionary work and abolition had been illustrated at the Society’s Annual Meeting in May 1834 which was chaired by Thomas Fowell Buxton, M.P. and leader of the parliamentary anti-slavery lobby.35

Three days after John Williams’ arrival in June 1834, around £3000 was raised at an Anniversary meeting of the East Lancashire Auxiliary in Manchester, addressed by Knill.36 Williams was soon enlisted to help, addressing the meeting of the Birmingham Auxiliary in September 1834.

Speaking at Carr’s Lane Chapel, where ‘Pomare’s Idol Gods’ had been exhibited in 1820, shortly after the construction of the chapel, Williams thanked the congregation for the many gifts of ironmongery they had sent him in the Pacific. It was here that John Angell James, prominent Birmingham minister and, like Williams, a former student at Gosport Academy, first asked him to describe the construction of the Messenger of Peace.37

Williams’ descriptions of the Pacific emphasised its spiritual darkness, dwelling on ‘idol-worship’, infanticide and human sacrifice, but blended this rhetorical othering with what Jane Samson has called brothering – a parallel emphasis on a potential for redemption.38 In discussing human sacrifice, Williams asked his audience to imagine their distress if their own husbands and fathers had been selected as a victim, declaring:

And do not for a moment imagine, my dear hearers, that because these wives, and sons and daughters, are of a different colour from yourselves, that they are without natural affection. ‘God hath made of one blood all that dwell upon the earth’.39

Alongside speaking at meetings, Williams engaged the Directors in London, persuading them to support the establishment of a theological college at Rarotonga but struggled to get them to take on the expense of a missionary ship. An account of the Tahitian missions, written for the Directors, was printed in the Missionary Magazine in April 1835, where he was introduced in relation to a history of sending ‘idols’ home as indications of conversion:

By the enterprise and diligence of Mr. Williams in conjunction with his brethren, the gospel has been extended to the numerous islands situated to the west and south of Tahiti, where idolatry has been abolished, whence coffins-full of dead gods have been shipped for England, and where flourishing churches now exist.40

Interior of Carr's Lane Chapel

Ink drawing by J. Porteous Wood

Williams acknowledged many challenges, two decades after the initial conversion of Tahiti, including the widespread use of ‘ardent spirits’, but suggested this was not unexpected since:

Christianity imposes great restraints upon a people who have been habituated to the unrestrained influence of passion; this was restrained while the excitement of novelty lasted, but as soon as that subsided, these restraints became irksome.41

Nevertheless, he asserted that ‘in all the lamentable defections, from Christian doctrine and purity… I have never heard of one individual that has ever thought of returning to the worship of their former gods’.42

At the Annual Missionary Meeting in May 1835, Williams reported that the British and Foreign Bible Society were printing 5000 copies of the New Testament in Rarotongan, while the Religious Tract Society were producing 10,000 Rarotongan tracts – ‘little messengers of mercy to send on their embassies of love’. He also appealed for ‘ten missionaries to occupy fields already white unto harvest’.43

Never lacking in ambition, Williams suggested that in addition to the missions started in Samoa, there remained ‘the Fiji Islands… the Hebrides… Solomon’s Archipelago… New Caledonia; New Guinea; New Ireland, &c., with their adjacent islands.’ He made a case for Protestant missionary societies to coordinate their efforts (partly to exclude Catholics), arguing that the rapid expansion of Christianity in the Pacific was ‘unrivalled in the history of Christian enterprise’, ‘excepting Apostolic times’.44

While the Society’s income for the year after his return reached £53,000, the highest ever, Williams urged supporters to make ‘utmost exertions to raise the funds of the Society from £60,000 to £100,000 during the coming year’. In addition to their usual evangelical middle class circles, he suggested an appeal could be made to the British royalty and nobility, giving them ‘an opportunity of enrolling their names among the friends of the Redeemer and benefactors of the human race’.45

New Testament in Rarotongan

One of 5000 copies printed by the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1836.

On 5 October 1835, a newly built Mission House was dedicated at Blomfield Street, attended by six new missionary recruits, soon to depart for Samoa.46 Part of the reason the new building was necessary was ‘the great increase in the business of the Society which has taken place, during the last few years’.47

In December 1835, in place of its usual portrait, the Evangelical Magazine even included a print showing the ‘Elevation of the New London Missionary House’, built on the corner of Blomfield street and New Broad street at a cost of just over £3000.48 Alongside offices, it had a ‘dry and ample warehouse-room, and a Museum’.49 The Museum, where items presented by John Williams were displayed, was built in surplus land at the back of the building, accessed through double glass doors at the far end of the entrance hall.50

During 1836, John Williams continued to tour the country, addressing meetings of Missionary Auxiliaries (often five or six a week), while working on his book. In more informal settings, Ebenezer Prout remembered him bringing out cases ‘of curiosities which he had brought from the islands’ in order to speak at length about:

A singular medley of idols, dresses, ornaments, domestic utensils, implements of industry and weapons of war; and not infrequently, Mr Williams arrayed his own portly person in the native tiputa and mat, fixed a spear by his side, and adorned his head with the towering cap of many colours, worn on high days by the chiefs; and, as he marched up and down his parlour, he was as happy as any one of the guests whose cheerful mirth he had thus excited. To this exhibition, he would add explanations of each relic; naming and sometimes describing the island from which he obtained it; the use of the object, or the customs connected with it; and various other interesting particulars.51

Such items were sometimes given to guests who displayed a particular interest in them, and there are examples in museum collections such as the Field Museum in Chicago and the Auckland Museum, which seem to have been given to Prout by Williams.

A portrait of Williams was painted by Reginald Easton, a version of which appeared in the Evangelical Magazine for May 1836.52 Williams also addressed the Society’s Annual Meeting that month, using the history of the Tahiti mission and its past discouragements to provide encouragement in the light of the recent expulsion of missionaries from Madagascar (Chapter 19):

While the British Christians were praying at home, God was mercifully answering their prayers abroad, for while the vessel was on its voyage to Tahiti, conveying letters of encouragement to the Missionaries, another vessel was on her way to England, bearing not only the glad news of the downfall of idolatry, but also the rejected idols of the people, which were now to be found in the Missionary Museum.53

Williams recounted donations of coconut oil made by Tahitians in support of the Missionary Society, before appealing to ‘philanthropists, merchants, ship-owners, with British seafaring men generally’, as part of his pitch for a missionary ship. The speaker who came after him suggested it was hard to follow someone who ‘could explain “I have discovered a country; I have arranged a language; I have Christianised a people’.54

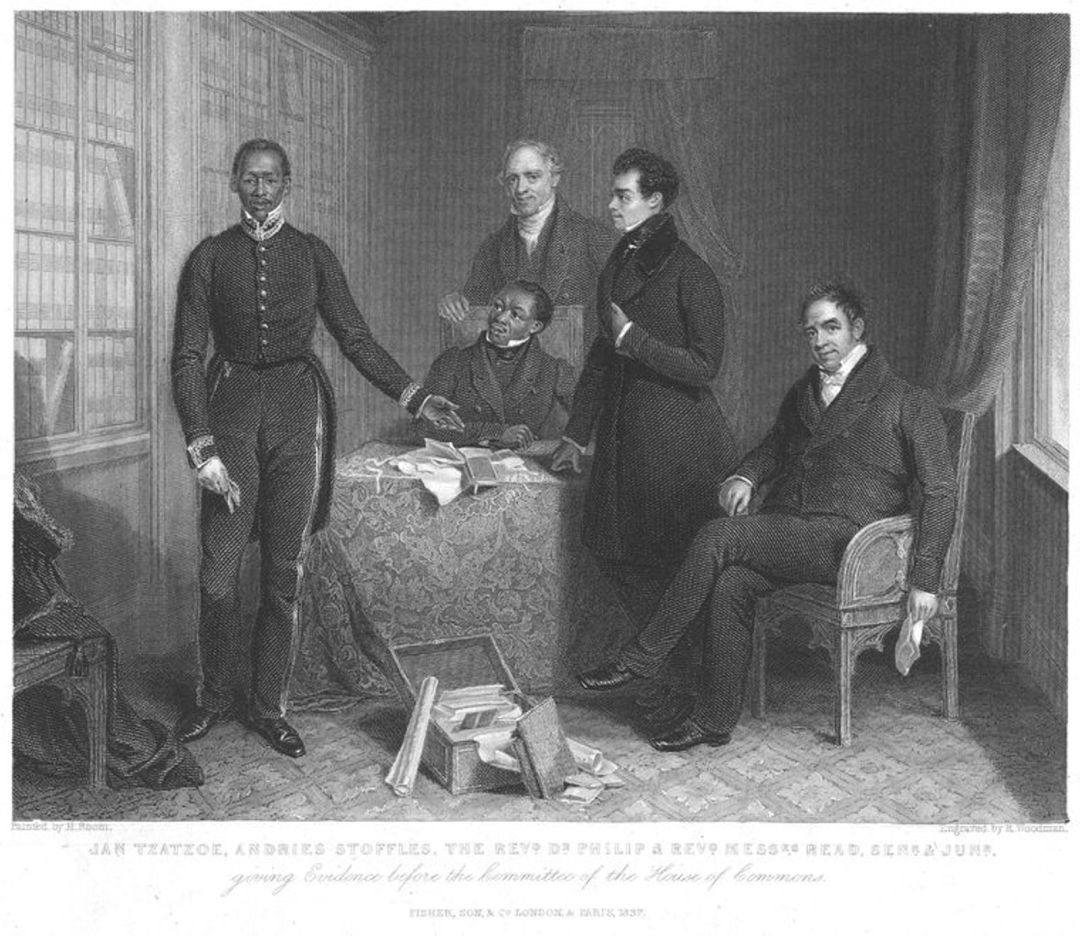

Shortly after this meeting, London welcomed further arrivals from the mission field – John Philip, superintendent of the South African missions, accompanied by Jan Tzatzoe chief of the amaNtinde Xhosa lineage, Andries Stoffels, a Khoe church deacon at the Kat River settlement (established in 1819 for dispossessed Khoe in frontier lands), as well as Mr James Read junior, the son of the Rev. James Read senior (one of the early Bethelsdorp missionaries – Chapter 2) and Sara Elizabeth Valentyn, who was Khoe.55

The arrival of three African Christians was a spectacle, inviting comparisons to the visit made by their fellow countrymen over three decades earlier (Chapter 2). Travelled expenses were at least partly met by the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, the Indian-born evangelical Charles Grant (Lord Glenelg), to enable them to give evidence to the Parliamentary Select Committee on Aboriginal Tribes (British Settlements).56

The Select Committee had been established by Thomas Fowell Buxton in March 1835, following the abolition of slavery, but arose partly in response to a conflict engulfing South Africa’s Eastern Cape. Its terms of reference appointed it:

to consider what Measures ought to be adopted with regard to the Native Inhabitants of Countries where British Settlements are made; and to the neighbouring Tribes, in order to secure to them the due observance of Justice and the protection of their Rights; to promote the spread of Civilization among them; and to lead them to the peaceful and voluntary reception of the Christian Religion.57

Philip, together with Tzatzoe, Stoffles and Read, addressed the select committee in June – an image of Tzatzoe giving evidence was commissioned from Henry Room, regularly employed as a painter by the Society (Chapter 31). John Willians also addressed the committee in July, and a special missionary meeting was arranged at Exeter Hall for 10 August. An account of the event in the Missionary Magazine described the Africans as ‘savage-born, but new-created men’:

There were men upon the platform, on whom, although differing from ourselves in colour, every eye was fixed with hallowed and intense delight — men, who came amongst us as harbingers of a brighter day for Africa — earnests of an abundant harvest yet to come, and representatives of thousands of their countrymen who have embraced the truths of Divine revelation.58

Elevation of the New London Missionary House, Blomfield Street, Finsbury

Originally published in The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for December 1835, opposite p.485

To'o from Rurutu

Given to Ebenezer Prout by John Williams. Part of the Oldman collection, acquired by the New Zealand Government in 1948

Rev. John Williams, Missionary at Raiatea

Originally published in The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for May 1835, opposite p.177

Jan Tzatzoe, Andries Stoffles, the rev.d Dr. Philip & rev'd Mess'rs Read, Sent. and June., giving evidence before the committee of the House of Commons

Originally published as Plate 1 in The Christian keepsake and missionary annual 1837, edited by William Ellis, opposite p.485 (Google books). Engraving by Richard Woodman, original painting by Henry Room.

John Campbell, who had met Tzatzoe on his second journey to South Africa nearly two decades earlier, was keen to remind the meeting of their long connection. Speaking in Dutch, Tzatzoe contrasted long-term conflicts across South Africa with the peace that Christianity promised, deploying his own rhetoric of ‘othering’ and ‘brothering’ to make a distinction between the people in England and the settlers in South Africa:

Many Englishmen in the colonies are bad, but I will hardly believe that those Englishmen belong to you. You are a different race of men – they are South Africans – they are not Englishmen.59

Andries Stoffles, also speaking in Dutch, recalled the beginnings of the mission in South Africa, stating:

I am standing on the bones of your ancestors, and I call upon you, their children, to-day, to come over and help us. Do you know what we want? We want schools and schoolmasters — we want to be like yourselves. You see before you two men of two different nations. You who have put your money into plates, but who never saw the fruits of our labours, I stand here before you as the fruit of your exertions.60

Read junior, however, reminded the audience of the explicitly political role taken by missionaries in South Africa:

Your Missionaries have stood betwixt the task-masters and the oppressed, in a country where both the oppressed and the oppressor were degraded almost to the level of the beasts that perish.61

These ‘African brethren’, or ‘African converts’ as they were sometimes known, addressed meetings across the country for several months, frequently speaking on the same platform as John Williams. On 25 October 1836, James Read junior was ordained as a missionary, shortly before he returned to South Africa with Andries Stoffles on account of their declining health.62

Tzatzoe and James Read senior, however, remained in Britain another year, during which Tzatzoe’s celebrity continued to grow. His portrait appeared in the Evangelical Magazine for May 1837, a year after Williams (and following Stoffles in February).63 The following month it was announced that William Cowan had prepared a coloured lithograph portrait of Tzatzoe for sale (one of which survives at the British Museum – 1878,0112.114).64

When Williams’ book was published in April 1837, he arranged for 50 copies to be sent to members of the nobility, as well as members of the royal family, including the mother of the heir to the throne, who was encouraged to ‘allow your beloved and august daughter to honour the volume with a perusal’.65

Both Williams and Tzatzoe addressed the Society at Exeter Hall on 10 May 1837, the largest and longest Annual Meeting ever held (at which Charles Mead also spoke – Chapter 14). Tzatzoe declared:

If it had not been for the Missionaries there would not now be a Caffre nation; we should have been extinct; the Missionaries saved us. I take this opportunity of thanking the present Government of England… which has given us our rights and returned our country. I shall have very great news to tell my people when I arrive in Africa.66

Rev. W. H. Medhurst, who returned from Batavia in August 1836, made a case for the importance of a mission to mainland China, suggesting that a vessel might be launched ’to sail along the coast of China, to be employed not in seeking lucre, but in spreading the blessings of Christianity’ in order to counteract the effects of the opium trade (Chapter 17). 67Mention of a missionary ship seems to have prompted John Williams to rise from his seat to underline his own case for the Pacific mission.

Great things had been expected from the Aborigines Select Committee, with John Philip working behind the scenes on the report in collaboration with Anna Gurney (the wheelchair bound cousin of Buxton’s wife, Hannah Gurney) and Sarah-Maria Buxton (Thomas Fowell Buxton’s sister), who worked tirelessly compiling and summarising information from a cottage in Norfolk.68

Although land taken during the war in South Africa was returned and Governor D’Urban recalled, when it came to the publication of the report in June 1837, in the run up to an election prompted by the death of the King, the more controversial details were excised by Sir George Grey of the Colonial Office. This act of censorship, including the removal of details the humiliating treatment of the body of the Hintza, King of the Gcaleka Xhosa, resulted in a report Anna Gurney described as ‘like a table without a leg’.69

This appears to have prompted the establishment of the Aborigines Protection Society, which published the original uncensored report in full.70 The new society brought together missionaries, abolitionists and humanitarians such as Saxe Bannister, former Attorney-General in New South Wales, who had been an important ally of Lancelot Threlkeld (Chapter 10). The first annual report of the Aborigines Protection Society, declared:

The abhorred and nefarious slave traffic, which has engaged for so long a period the indefatigable labours of a noble band of British philanthropists for its suppression and annihilation, can scarcely be regarded as less atrocious in its character, or destructive in its consequences, than the system of modern colonization as hitherto pursued.71

While the society was ‘anti-colonial’ in opposing the political influence of settlers and traders, it remained ‘imperialist’ in its imagination of a humanitarian and Christian empire, within which ‘others’ would be enabled to become ‘brothers’. Krishnan Kumar has suggested that The Making of English National Identity, with its themes of liberty, prosperity and progress, was marked by a ‘Missionary Nationalism’, a key feature of which he suggests is ‘the attachment of a dominant or core ethnic group to a state entity that conceives itself as dedicated to some large cause or purpose’.72

Andries Stoffles

Originally published in The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for Feburary 1837, opposite p.52 (Google Books). Engraved by Jenkins from an original drawing by John Wesley Jarvis.

Jan Tzatzoe, A Christian Child of the Amakosa, South Africa

Originally published in The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for May 1837, opposite p.193 (Google Books). Engraved by W. Holl from a painting by Henry Room.

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library

Jan Tzatzoe, Caffer Chief, April 10, 1837

Hand coloured lithograph by William Cowan, printed by J. Graf. Advertised for sale in June 1837.

We can arguably see this articulated clearly by the alignment of missionary and imperial agendas at the Aborigines Select Committee. Conflicts from the edges of empire had played out in London through the Select Committee, resulting in an apparent victory, despite the necessary concessions made by Buxton in relation to the report.73

It soon became time for the missionaries to return to their stations and on 17 October 1837, the London Missionary Society held a Valedictory Service at Exeter Hall to mark the departures of Charles Mead for India, John Philip for South Africa and John Williams for the Pacific. With thirty-five new missionary recruits, the three veterans headed ‘the largest Missionary Company sent forth by the Society at any one period since the sailing of the ship Duff in 1796’.74

When John Philip addressed the meeting, he directed its attention to ‘the finest collection of natural curiosities which perhaps was ever seen in this world’, displayed since June at Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, by Dr Andrew Smith, following his return from an expedition to explore the African interior, using LMS mission stations as jumping off points:

look on the walls of the Egyptian Hall, and you will see pictures, of men feeding like brutes – throwing the spear at each other – engaging in rude dances – having no trace of any thing like education or civilisation. While you gaze, you will find it difficult to persuade yourselves that you are looking at human beings. But on the same walls you will see depicted the Missionary stations; and there you will see people decently clothed; having gentleness in their countenances; exercising the habits of civilised life; exhibiting what Christianity is able to effect for a people.75

‘Othering’ and ‘brothering’ could be evoked as a contrast in relation to the developing civic exhibitionary complex, remaining deeply entangled with the missionary enterprise. Philip was followed by Jan Tzatzoe, who seemingly embodied this contrast within his own person, thanking the audience for their support before asking for God’s blessing on them.

John Williams, when he spoke, expressed a hope that the coming Victorian period would mark a period:

when the Missionary cause will have such a hold on the public mind that the greatest wealth, the mightiest influence, the most brilliant talents, and the highest rank in the British nation, will be consecrated to it.76

Williams suggested that in contrast to the warfare of preceding periods, Victoria’s reign might diffuse ‘all over the world the knowledge and blessings of that Christianity upon which our own nation’s superiority is based, and in which the present and future felicity of the human family is concentrated’ – a fairly clear statement of ‘Missionary Nationalism’, although one suspects the nation he had in mind was as much British with English, having been born in England to Welsh forbears himself.77

Williams was keen to counteract the ‘speculations of philosophers’ and phrenologists who ‘have been describing the colour, the capacities, the weight of the brain’ with the lived experience of missionaries ‘from among all tribes on the earth’, who could stand before the civilised world and say ‘God has made of one blood all nations of men that dwell upon the face of the earth.’78

Making the case for the special place of the Pacific mission, Williams suggested that there were ‘between 200,000 and 300,000 people wearing and using articles of British manufacture’, while missions had also made many of harbours safe for British maritime shipping. He suggested that the conversion of Tahiti had been the most important turning point in the Society’s history, as well as the beginning of the current enthusiasm for missions, suggesting:

No. 138 Matabile war dance, 1835

Monochrome Watercolour painted when visiting the kraal of Mzilikazi near the Tolane River.

Note the darkness of the scene.

No. 46 Mr Archbell's Congregation at Thaba Unchoo - 1834

Monochrome Watercolour painted by Charled Bell at the Wesleyan Mission station at Thaba Nchu in late 1834

Note the concentration of the light at the front of the congregation, among those wearing European dress.

Every one acquainted with the history of the Missions must know that the Missionary feeling was at a very low ebb till the importation of the rejected idols of Pomare, and from that time to the present the Missionary feeling has been increasing with accelerated progress.79

Williams ended his speech by declaring:

We only want one thing, and that is a ship in which to take the voyage. I am not about to appeal to you – from that I am restricted; but I tell you what I want, and you can give it me. I have made application to her Majesty’s government to be supplied with a ship, and I anticipate the pleasure of carrying England’s commerce, civilisation, and Christianity to distant regions, in a vessel the gift of England’s Queen.80

Explaining that he was yet to have a definitive answer from the Government, he told the meeting £600 had been promised by supporters, suggesting a thousand friends might give a sovereign each, particularly if advertisements were sent to Liverpool and Birmingham.

Soon after the meeting, Mead, together with the new recruits sailed for Travancore, and on 25 November Philip, Tzatzoe and Read senior returned to South Africa with a new missionary by the name of Gottleib Schreiner and his wife Rebecca Lyndall (the parents of the novelist Olive Schreiner).81

Only on 18 December 1837 did Williams receive a definitive answer from Sir George Grey, confirming it would not possible for the British State to supply him with a Missionary ship because of the precedent it would establish. By that time, Williams’ Narrative had sold over 4000 copies, more than any previous missionary account.82

On 27 December an ‘Appeal for the Purchase of a Missionary Ship’ was circulated by the Society, and very quickly returned enough to allow the Camden to be purchased for £1600. When a stranger in Birmingham handed him £100, offering two or three hundred more, Williams stated that ‘It was a delightful illustration of the blessed influence which the Narrative is exerting in the country’.83

In February, Williams discovered that Captain Robert Morgan, an unusually religious captain whom he knew from the Pacific, had just arrived in London, following a shipwreck on Australia’s north coast. Morgan was quickly recruited to take charge of the Camden, which following its refurbishment was opened to visitors at West India Docks for several days before being towed to Gravesend on 9 April, awaiting its departure.

An Appeal for the Purchase of a Missionary Ship

Published in the Missionary Magazine and Chronicle for Feburary 1838, p.28

The Missionary Brig Camden

Which sailed from London on the 11th of April 1838… having on board the Revd John Williams and 9 other Missionaries and their wives. Dedicated to the London Missionary Society and the friends of the Mission in general by their humble Servant John Snow, publisher. Dean & Law.

The Camden is shown passing the Needles, off the Isle of Wight. Print at Royal Museums Greenwich PAH8474

On the way down the English Channel, the Camden passed the Isle of Wight, depicted in another colour image image published by John Snow, and on 18 April left Dartmouth, where another valedictory service was held. The Missionary Magazine provided updates on the Camden’s progress for readers, including its meeting with an American whaler in the Atlantic on 2 June.84

The Camden arrived at Cape Town on 1 July, remaining for just over two weeks, enabling Williams to visit the Society’s schools with John Philip.85 The next stop was Sydney on 8 September 1838, where the Camden’s arrival prompted the establishment of an Auxiliary Society, as well as the production of another image, showing her leaving Sydney harbour on 25 October 1838.86

Sydney Cover, Port Jackson

The steam boat Australian accompanying with numerous friends on farewell of the missionary brig Camden, Octover 25th 1838.

Note the Indigenous family framed by the gateway near the foreshore.

Hand coloured aquatint, engraved by S.G. Hughes from a a drawing by Chs. Rodius. Published at Syney by N.P. Ringman, 1838.

In January 1840, a letter from Williams was published in the Missionary Magazine, written at Tahiti at the end of March 1839, in which he described the missionaries at Samoa looking meagre and emaciated, while those in the Cook Islands had not been visited in three years, underpinning the ongoing need for a missionary ship.87

It must have come as a real shock when just four months later, in May 1840, the magazine reported the ‘Mournful Death of the Rev. John Williams’, alongside an extract reprinted from the Bengal Hurkaru, published at Calcutta on 12 February, itself taken from an article in the Australian on 3 December 1839. This reported that after a successful landing at Tanna on 19 November 1839, the Camden had visited the neighbouring island of Erromanga the following day. There both Williams, and ‘Mr Harris’ were clubbed to death on the beach. Unable to retrieve their bodies, Captain Morgan had returned to Sydney.88

The Missionary Magazine’s cover in June 1840 unusually did not feature an image. Rather, a thick black line surrounded a a printed letter from Captain Morgan, under a headline announcing the ‘Death of the Rev. John Williams’. Morgan explained that James Harris had been on his way to England to volunteer as a Missionary to the Marquesas.89

At Tanna, Williams evidently remarked that ‘he had never been received more kindly by any natives’, leaving three Polynesian evangelists and one of their sons there. At Dillon’s Bay at Erromanga, Williams, Harris, Cunningham (British Vice-Consul a Samoa), together with Captain Morgan and four sailors had approached the shore in a whale-boat. Morgan described the people as ‘a far different race of people to those at Tanna, their complexion darker, and their stature shorter; they were wild in their appearances and extremely shy’.90

Throwing beads to encourage them to come closer, Williams had given those on the beach fish hooks and a small looking-glass. After a bucket was filled with fresh water, and coconuts given to those in the boat, Harris had been first to wade ashore. Although no women could be seen and the men seemed afraid, Williams followed, giving sections of printed cloth to those on the beach.

Next went Cunningham, and when it seemed safe, Morgan. Before Morgan had gone a hundred yards, the boat’s crew called him back, and he caught sight Williams and Cunningham running (Harris was the first to be killed). Cunningham reached the boat alongside Morgan, but Williams ran to the sea and stumbled as he reached the water’s edge, when he was struck by the man pursuing him with a club, before another ‘pierced several arrows in his body’.91

When the boat approached Williams’ body, an arrow was fired into the boat, narrowly missing one of the seamen, followed by a hail of rocks. Returning to the Camden, Captain Morgan ordered a gun to be loaded with power and fired, but the Erromangans dragged Williams’ body out of sight.

The Editors of the Missionary Magazine were quick to remind their readers that ‘awful and inexplicable as is the dispensation, let the church be still and know that He who has permitted the early fall of his devoted servant is GOD. Though all must mourn, let none complain.’ This account was followed by an appeal to increase the Society’s income to £100,000 during the coming year.92

In July, ‘An Appeal on Behalf of the Widow and Family of the late Rev. John Williams’ on behalf of the Directors of the London Missionary Society was announced, while an article appeared in the Evangelical Magazine under the title of The Martyred Missionary.93 By August, the Missionary Magazine announced that Ebenezer Prout was preparing a Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to the South Sea Islands, and it seems that his other old friend, George Baxter, likely began his own project of commemoration at around the same time.94

In early May 1841, a year after news of Williams’ death had reached London, newspapers announced the publication of:

The PAIR of splendid PRINTS, in Oil Colours, representing the deeply-lamented Missionary, THE REV. JOHN WILLIAMS, Landing at Tanna, and the last day of this devoted Missionary’s life at Erromanga.95

They were sold for one pound, five shillings each, and purchasers of the pair were promised a description by J. Leary, one of the survivors of the massacre, as well as ‘an Account of the Islands when visited by Capt. Cook and Capt. Dillon’. According to the accompanying pamphlet, on hearing news of the death of his friend Baxter ‘thought he could not better evince the sincerity of his regret for the loss of his friend than by dedicating his art and labours to perpetuate the memory of so estimable a man’.96

Unlike The Departure of the Camden, Missionary Ship, which had been published by John Snow, these prints were published by Baxter himself. While The Departure of the Camden was dedicated to the London Missionary Society, Baxter promised a contribution from the profits of these new prints to the ‘fund now being raised for Mrs Williams’, having already given fifty guineas ‘as a kind of ‘first fruits’’, before the prints went on sale.97

Broken pocketwatch of James Harris

Recovered from Erromanga along with his best handkerchief, as well as the club that killed John Williams, which for many years were kept at the Mission House in London.

Photographed in 2010, transferred to the National Maritime Museum in 2012.

By comparing Baxter’s published image of Williams’ death on Erromanga to an annotated watercolour sketch, as well as Webber’s 1785 image of the death of Captain Cook, the Australian art historian, Bernard Smith, suggested that Baxter deliberately made the Erromangans darker in complexion and the missionary ‘more heavenly’ in order to ‘suggest the saintliness of Williams and the spiritual depravity of his murderers’.98

Smith suggested that the ‘remarks’ inscribed on the sketch ‘clearly sought to make the illustration more amenable to evangelical taste’, however it is not clear that they all fulfil this purpose. It is possible that at least some recorded remarks made by someone who had actually witnessed the scene, such as J. Leary, whose eyewitness account was printed to accompany the images.

Two notes state that the men attacking Williams ‘should be in deeper water’, which may simply be a question of accuracy since an evangelical interpretation of being in deeper water might bring those responsible for Williams’ death closer to baptism. Other notes, selectively quoted by Smith appear to be slightly more ambiguous than he suggests: ‘William I think is more Heavenly in the other sketch, on ?Triate’s Paper he fell forward, not backward’ while another states ‘The Natives. Dark complexion’ and ‘group attacking Harris in the Brooke’.

In making Baxter’s depiction of Williams’ death at Erromanga representative of missionary presentations of the ‘ignoble savage’, ‘a squat, swarthy, highly emotional type of being completely lacking in any personal dignity’, Smith ignored the image that was originally published along with it, that of Williams at Tanna.99

In this, a barefoot Polynesian teacher in trousers and a shirt stands on a plank linking the dry land to the missionary boat, gesturing towards Williams while looking at a local chief. Williams is shown standing at the front of the boat ‘with his hat in hand, waiting for permission to land’.100 When the two prints are placed alongside each other, although the scenes on the beaches are very different, the outline of the coast and the mountains in the background suggests a considerable degree of lateral symmetry.

The Reception of the Rev. J. Williams, at Tanna in the South Seas, the Day Before He Was Massacred

Steel engraving coloured with wooden blocks on tan wove paper, laid down on buff board.

Published by George Baxter in 1841.

The Massacre of the Lamented Missionary, the Rev. J. Williams and Mr Harris

Steel engraving coloured with wooden blocks on tan wove paper, laid down on buff board.

Published by George Baxter in 1841.

In fact, the two prints were created to be displayed alongside each other, and the scene at Tanna suggests an alternative possibility for Erromanga. Baxter himself referred to the relationship between the two images as a ‘melancholy contrast’, with the same boat, ‘natives’ and Missionary, ‘but alas! In how changed a position’.101

Part of the visual symmetry that links Baxter’s images relates to the sky behind Williams. This is suffused with bright light, suggestive of missionary rhetoric which regarded overseas mission as a means of shedding light into darkness.102 By including cloth, mirrors and boxes of provisions in the boat at Tanna, Baxter connected this ‘enlightenment’ project to the charitable gifts made by British supporters of the mission, just as he included them in his Departure of the Camden, Missionary Ship. Missionary work overseas was depicted as a charitable gift.103

If the scene at Tanna depicts the welcoming acceptance of this gift, the ‘massacre’ at Erromanga illustrates the opposite: a gift violently rejected. In his essay on The Gift, Marcel Mauss suggested that while those involved in gift exchanges are in theory ‘free agents’, in practice they have an obligation to give as well as to receive: ‘To refuse to give….just as to refuse to accept, is tantamount to declaring war; it is to reject the bond of alliance and commonality’.104

The Erromangans’ refusal to receive the charitable advances of Williams dehumanised them in comparison to their neighbours at Tanna, and this difference is visualised by Baxter’s depiction of their physical appearance. According to Baxter’s description of the scene at Erromanga ‘every countenance [is] expressive of the most diabolical malice and rage…they all seem intent on the work of death’.105 His use of the word ‘diabolical’ suggests that Baxter may have regarded the Erromangans as motivated by satanic forces, just as his contemporary Mead saw evidence for the work of the devil in South Indian religious practices (Chapter 14).

It would be easy to exclusively concentrate, like Bernard Smith, on Missionary forms of ‘othering’, since the description and depiction of gruesome pre-Christian practices such as human sacrifice formed an important part of missionary rhetoric, deployed in fundraising campaigns such as those of John Williams, as well as in Missionary publications. To do so without recognising their mirror image – the ‘brothering’ described by Jane Samson, premised on a project of redemption and reform – would be to fail to acknowledge the full picture – the light alongside the shadow – and would arguably simply position missionaries themselves as ignoble ‘others’.

Given regular Missionary insistences that all humans were ‘of one blood’, words taken from the English Bible (Acts 17:26) where they form part of St. Paul’s speech to the Athenians, as a motto by the Aborigines Protection Society, we can begin to recognise Missionary ‘othering’ as not primarily racial, but rather essentially spiritual. Spiritual depravity marked the absence of a connection to God, a condtion to which Europeans, including South African and Australia settlers, could be as vulnerable as non-Europeans.

Baxter’s depiction of the chief at Tanna with an elaborately wrapped loin cloth and a white feather in his headdress, carrying a finely worked club that is more a sceptre than an offensive weapon, is suggestive of his peaceful intentions, but it was presumably also intended to suggest his openness to the possibility of salvation. Without such openness, marked by an acceptance of what Mauss called ‘the bond of alliance and commonality’, evangelical mission, even when underpinned by the practical resources offered by a missionary ship such as the Camden, remained an impossible project.

Acknowledgements

Missionary ships have long been something of a fascination, seemingly capturing evangelical enthusiasms in artefactual form. I was lucky enough to be awarded a Caird Research Fellowship at the National Maritime Museum to pursue the topic in 2015.

Gréine Jordan began her collaborative doctoral research with the National Maritime Museum in 2018, which she has recently successfully completed. Central to her thesis was the parallel between the John Williams missionary ships and the Juvenile Missionary Magazine, both launched in 1844. This chapter is intended to supply the prehistory for that complex.

I am very grateful for the ongoing guidance and maritime input of Robert Blyth, Senior Curator of World and Maritme History at the National Maritime Museum, as well as John McAleer, who reminded me to always italicise ship names while writing this chapter! John was kind enough to give this chapter a close reading and I am extremely grateful to him for spotting the various typos which had infiltrated the text…

Comments

This is an experiment in writing – intended to stretch the idea of the academic monograph.

I am keen to recognise and incorporate the input and expertise of others into the writing process, so I would welcome any comments or feedback.

Notes

1 (1838) Departure of the Missionary Ship Camden for the South Seas, Missionary Magazine and Chronicle for May 1838, p.247: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5PUDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=RA1-PA247#v=onepage&q&f=false ; Rev. J. Campbell (1838) Narrative of the Excursion to the Missionary Ship, and subsequent events. In,The Missionary’s Farewell; Valedictory Services of the Rev. John Williams, Previous to his Departure for the South Seas, p.107: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1PtiAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=williams%20missionary%20enterprises&pg=PA107#v=onepage&q&f=false

2 Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 507: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA507#v=onepage&q&f=false

3 Lewis, C. T. C. (1908). George Baxter (Colour Printer) – His Life and Work – A Manual for Collectors. London, Sampson Low, p. 16: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=yale.39002085230085&seq=48&q1=Camden

4 Rev. J. Campbell (1838) Narrative of the Excursion to the Missionary Ship, and subsequent events. In,The Missionary’s Farewell; Valedictory Services of the Rev. John Williams, Previous to his Departure for the South Seas, p.120: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1PtiAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA121#v=onepage&q&f=false

5 Genesis 28: 19; Intriguingly, the letters on the flag appear are reversed, compared to the earlier image, perhaps because it had been pointed out that this was more correct with the wind in that direction.

6 Born in London, Williams’ ancestors came from Wales, where there were many auxiliaries supporting the LMS; (1838) Acknowledgements. Missionary Magazine and Chronicle for May 1838, p. 257; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5PUDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=RA1-PA257#v=onepage&q&f=false

7 Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 475: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA475#v=onepage&q&f=false. At the end of the previous page (474), Prout suggested that “It may be added that, although the Missionary Enterprises had been preceded by Ellis’s Researches, Tyerman and Bennet’s Journal, and other similar productions, and cannot therefore claim the character of an original conception, its success revived and increased the public interest in the important class of productions to which it belong, and exerted no feeble influence in daring other honoured labourers to employ their pen with the same important design.”

8 (1838) Farewell to Viriamu. Printed for Gratuitous Distribution on April 11, 1838, p.2: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=84j2LGhZmKQC&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=the%20missionary’s%20farewell&pg=PP8#v=onepage&q&f=false

9 (1838) Departure of the Missionary Ship Camden for the South Seas, Missionary Magazine and Chronicle for May 1838, p.249: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5PUDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=RA1-PA249#v=onepage&q&f=false

10 Rev. J. Campbell (1838) Narrative of the Excursion to the Missionary Ship, and subsequent events. In,The Missionary’s Farewell; Valedictory Services of the Rev. John Williams, Previous to his Departure for the South Seas, p.123: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=1PtiAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&pg=PA123#v=onepage&q&f=false

11 Eg. Endpages in Rowton, Nathaniel (1842) Theodora. A Treatise on Divine Praise. London: John Snow, p. 229: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=xWViAAAAcAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=%22A%20splendid%20coloured%20print%2C%20representing%20the%20Departure%20of%20the%20Camden%20Missionary%20Ship%22&pg=PT6#v=onepage&q&f=false

12 Baxter presumably witnessed and sketched the scene from the City of Canterbury.

13 As far back as 30 September 1823, Williams famously declared “I cannot content myself to a single reef, and if means are not afforded, a continent to me would be infinitely preferable, for there if you cannot ride you can walk, but to these isolated islands a ship must carry you.’ Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 189: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA189#v=onepage&q&f=false

14 Charles Pitman worried that Rarotongans might ‘feel a disgust against the Gospel’ on account of the amount of work they were being asked to undertake, but Williams persisted. See: Dixon, Rod (2022) Who really built Rev John Williams’ Rarotongan ship? Cook Islands News, Saturday 27 August 2022: https://www.cookislandsnews.com/internal/features/who-really-built-rev-john-williams-rarotongan-ship/

15 Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 255: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA255#v=onepage&q&f=false

16 Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 256: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA256#v=onepage&q&f=false

17 When confronted by a British naval officer who expressed doubts about his account of the Messenger of the Peace’s construction, Williams referred him to another naval captain who could confirm its details, having encountered the vessel; Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 256: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA256#v=onepage&q&f=false

18 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 151: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA151#v=onepage&q&f=false

19 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 153: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA153#v=onepage&q&f=false

20 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 170: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA170#v=onepage&q&f=false

21 Mathews, Basil (1915) John Williams, The Ship Builder (Oxford: Humphrey Milford).

22 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 222: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA222#v=onepage&q&f=false

23 Such connections were key to providing supporters with a sense of involvement in missionary activity, and no doubt link to the importance of textile within female networks (See – Chapter 14); Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 292: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA292#v=onepage&q&f=false

24 The same man was unimpressed by gifts of an axe, a knife, a mirror and pair of scissors, but happily returned to shore with a large mother-of-pearl shell; Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 296: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA296#v=onepage&q&f=false

25 Williams couldn’t help commenting on what he saw as the peculiarity of Wesleyan practices, including making converts take English Christian names at baptism.

26 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 320-321: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA320#v=onepage&q&f=false

27 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 343: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA343#v=onepage&q&f=false

28 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 405: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA405#v=onepage&q&f=false

29 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 418: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA418#v=onepage&q&f=false

30 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p. 438-438: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA438#v=onepage&q&f=false

31 It has unfortunately been impossible to identify and locate ‘Papo’.

32 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p.436: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA436#v=onepage&q&f=false

33 Williams, J. (1837). A narrative of missionary enterprises in the South Sea Islands; : with remarks upon the natural history of the islands, origin, languages, traditions, and usages of the inhabitants. London, Published for the author by J. Snow, p.438: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=5sEQAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA438#v=onepage&q&f=false

34 (1833) Return of Missionaries, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for September 1833, p. 422; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8tFGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA422#v=onepage&q&f=false

35 (1834) Annual Public Meeting, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for June 1834, p. 251: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=_scoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA251#v=onepage&q&f=false

36 (1834) East Lancashire Auxiliary Missionary Anniversary Held at Manchester, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for July 1834: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=_scoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA300#v=onepage&q&f=false

37 Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 411-412: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA411#v=onepage&q&f=false

38 Samson, Jane (2017) Race and Redemption: British Missionaries Encounter Pacific Peoples, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

39 Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p..419: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA419#v=onepage&q&f=false

40 (1835) South Seas, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for April 1835, p.167: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA167#v=onepage&q&f=false

41 (1835) South Seas, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for April 1835, p.168: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA168#v=onepage&q&f=false

42 Missionaries at Tahiti had introduced Temperance Societies, and Aimata Pomare IV, the daughter of Pomare II who became Queen of Tahiti in 1827, was said to be passing laws to prohibit the importation of spirits. Williams noted that a number of small vessels (20-35 tons) had been built by islanders to collect pearl shell, while others made rope to sell to visiting ships – although he blamed these ships for preferring to trade in ‘rum, or filthy stiff called by that name’; (1835) South Seas, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for April 1835, p.167: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA167#v=onepage&q&f=false

43 (1835) Annual Public Meeting, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for June 1835, p.260-262; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA260#v=onepage&q&f=false

44 (1835) Annual Public Meeting, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for June 1835, p.261; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA261#v=onepage&q&f=false

45 (1835) Annual Public Meeting, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for June 1835, p.262: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA262#v=onepage&q&f=false

46 (1835) Opening of the New Mission House, Blomfield Street, Finsbury, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for November 1835, p.481; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA481#v=onepage&q&f=false

47 (1835) New Building of the Use of the London Missionary Society, Missionary Chronicle for April 1835, p.161; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA161#v=onepage&q&f=false

48 (1835) Elevation of the New London Missionary House, Missionary Chronicle for December 1835, opposite p. 485; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA484-IA2#v=onepage&q&f=false

49 (1835) New Building of the Use of the London Missionary Society, Missionary Chronicle for April 1835, p.161; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=bsgoAAAAYAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA161#v=onepage&q&f=false

50 Campbell, John (1843) The Farwell Services of Robert Moffat in Edinburgh, Manchester, and London, London: John Snow, p. 134: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=ilJiAAAAcAAJ&vq=museum&pg=PA134#v=onepage&q&f=false ; (1878) The London Mission House, Chronicle of the London Missionary Society for January 1878 p.50; https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=JCsEAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=Evangelical%20Magazine%20January%201878&pg=PA50#v=onepage&q&f=false

51 Prout, Ebenezer (1843) Memoirs of the Life of the Rev. John Williams, Missionary to Polynesia, London: John Snow, p. 411-479-480: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=mMINAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA479#v=onepage&q&f=false

52 (1836) Rev.d John Williams, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for May 1836, opposite p. 177: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8NBGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA176-IA2#v=onepage&q&f=false

53 (1836) Annual Public Meeting, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for June 1835, p.265: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8NBGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA265#v=onepage&q&f=false

54 (1836) Annual Public Meeting, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for June 1835, p.268: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8NBGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA268#v=onepage&q&f=false

55 Elbourne, E. (2002). Blood ground : colonialism, missions, and the contest for Christianity in the Cape Colony and Britain, 1799-1853. Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press; Levine, R. S. (2011). A Living Man from Africa: Jan Tzatzoe, Xhose Chief, Missionary, and the Making of Ninteenth-Century South Africa, Yale University Press.

56 Keegan, T. (2016). Dr Philip’s Empire: One Man’s Struggle for Justice in Nineteenth-Century South Africa. Cape Town, Zebra Press.

57 (1836) Report from the Select Committee on Aborigines (British Settlements;) together with the Minutes of Evidence, Appendix and Index. Ordered by the House of Commons, to be Printed, 5 August 1836, p.ii: https://wellcomecollection.org/works/kbfbmq5m/items?canvas=10

58 (1836) Special General Meeting of the London Missionary Society, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for September 1835, p.420: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8NBGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA420#v=onepage&q&f=false

59 (1836) Special General Meeting of the London Missionary Society, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for September 1835, p. 422: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8NBGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA422#v=onepage&q&f=false

60 (1836) Special General Meeting of the London Missionary Society, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for September 1835, p. 423: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8NBGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA423#v=snippet&q=tzatzoe&f=false

61 (1836) Special General Meeting of the London Missionary Society, Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle for September 1835, p. 424: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=8NBGAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=evangelical%20magazine%20and%20missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA425#v=onepage&q&f=false