Carved in wood, about a foot in height and painted

Calcutta, September 1819

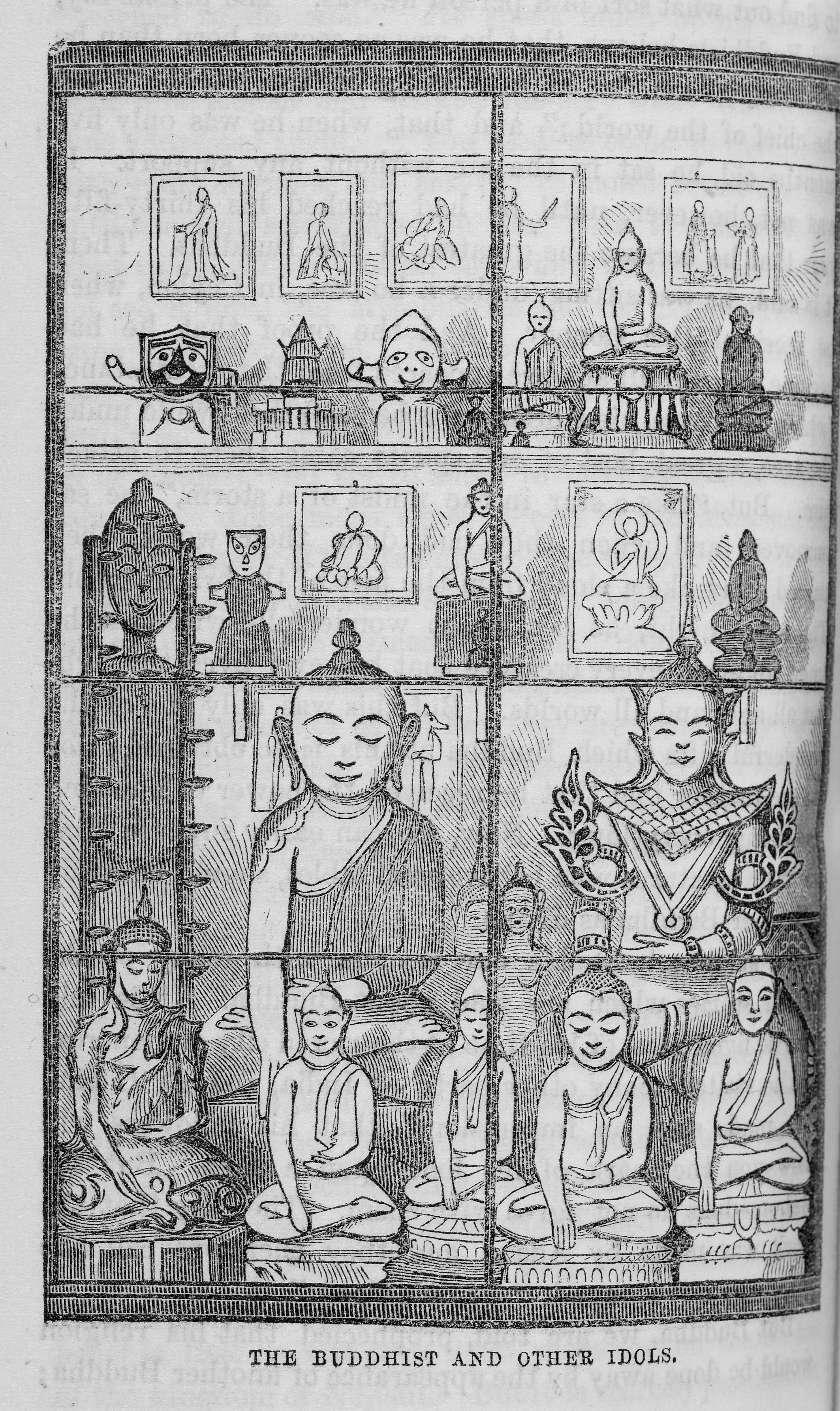

In September 1819, shortly after the ‘principal idol’ sent by Pomare II from Tahiti was conveyed around a Chapel in Falmouth, Cornwall, the Missionary Chronicle reported the arrival in London of further additions to the Missionary Museum. Sent by the Rev. Henry Townley as a gift from the Bengal Auxiliary Missionary Society, they were described as:

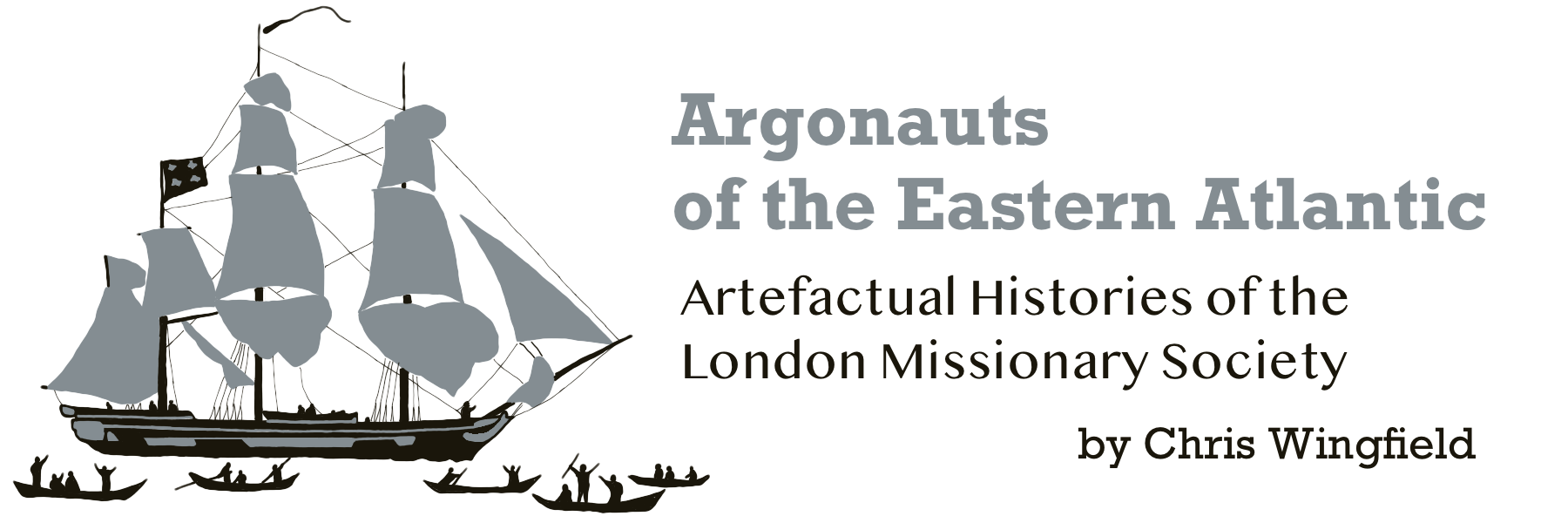

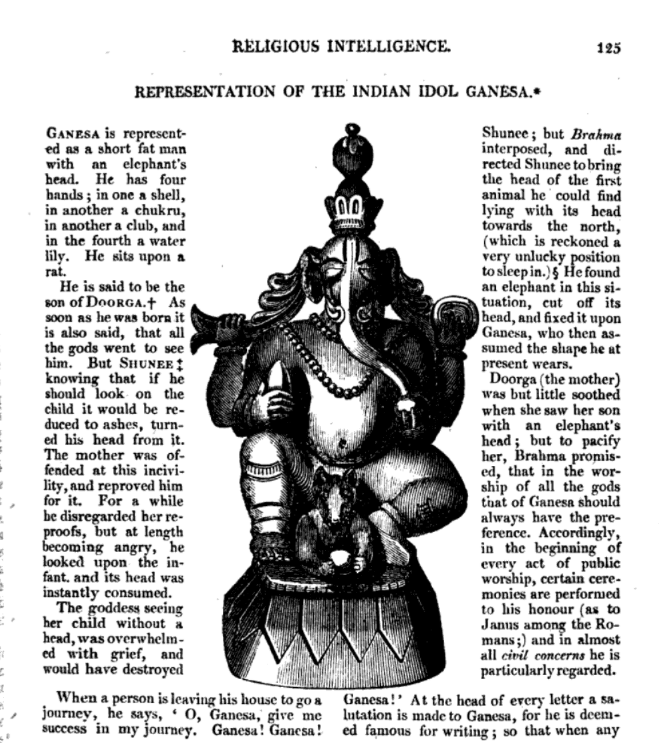

Twenty-two models of Hindoo deities, [carved in wood, about a foot in height, and painted] such as are ordinarily manufactured in that idolatrous country. Prints taken from these are intended to be given in the Missionary Sketches, accompanied by explanations from the Rev. Mr. Ward’s History of the Literature and the Religion of the Hindoos.1

A month after their arrival, the cover of Missionary Sketches featured nine of Townley’s models, each with the name of the God they depicted printed beneath.2

Abbreviated descriptions of each God, summarising Ward’s text, were given on the following pages. In a footer at the end of the descriptions, a paragraph clarified their intended message, positioning the work of missionaries in India as a direct continuation of a long-term battle against religious idols, documented in both the Old and New Testaments of the Bible:

These are specimens, Christian Reader, of the gods of the heathen in India, worshipped by more than a hundred millions of deluded people. These are the creatures of a corrupt imagination, and the workmanship of men’s hands — “they have mouths, but they speak not; eyes have they, but they see not; they have ears, but they hear not; they have hands, but they handle not; feet have they, but they walk not; neither speak they through their throat. They that make them are like unto them; so is every one that trusted in them. O Israel, trust thou in the Lord.” Psalm cxv. 5—10.3

These conjunctions of artefact, image and text illustrate the strong connections between items sent to the Missionary Museum and the images and texts that appeared in missionary publications. It seems likely that Townley, like John Smith in Demerara, had seen the early issues of Missionary Sketches from 1818, featuring the Trimurti from Elephanta, Mantis the Soothsayer from South Africa, and the Family Idols of Pomare from Tahiti. A fairly recent arrival in India, Townley had been sent to Calcutta by the Missionary Society’s Directors in 1816.

HINDOO IDOLS, Copied from Models, sent by the Rev. H. Townley, from the Bengal Auxiliary society

Missionary Sketches, No. VII, October 1819. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n24/mode/1up

The Rev. Mr. Ward, on the other hand, was William Ward, something of a veteran with nearly two decades of experience working for Baptist Missionary Society in India. In the aftermath of the French revolution, non-conformist churches in Britain had been associated with political radicalism, and the official line of the East India Company prohibited their missionaries from operating in areas it controlled. Sympathetic Company officials, however, had turned a blind eye to the activities of William Carey, the original Baptist missionary, after he arrived in India in 1793, particularly when he was officially employed on an indigo plantation.4

7The arrival of William Ward, along with three other Baptist missionaries and their families, in 1799, was harder to ignore. The recently arrived Anglo-Irish Governor-General, Richard Wellesley, pursuing a war against the French and their allies in Mysore, refused them permission to join Carey in Bengal. As a consequence, the Baptists established themselves at Serampore, a Danish controlled town less than twenty miles north of Calcutta, the capital of British India, much to Wellesley’s initial displeasure.5

Originally a printer and journalist from Derby in the British Midlands, Ward was responsible for the printing press at Serampore, established in 1800, where translations of the Bible were printed in Bengali, Marathi, Hindi and other Indian languages.6 The project of religious translation involved working closely with Indian scholars such as Ram Ram Basu, who was worked for Carey as his munshi (language teacher).7

When Governor Wellesley established Fort William College in Calcutta in 1801, it was Carey he appointed to teach Bengali, assisted by Basu. The project of translation operated in multiple directions—Sanskrit epics, the Mahabharata and Ramayana were published in Bengali in 1802-03. From 1805 the Baptists were even paid a stipend by the Asiatic Society at Fort William College to translate and publish Sanskrit texts in English.8

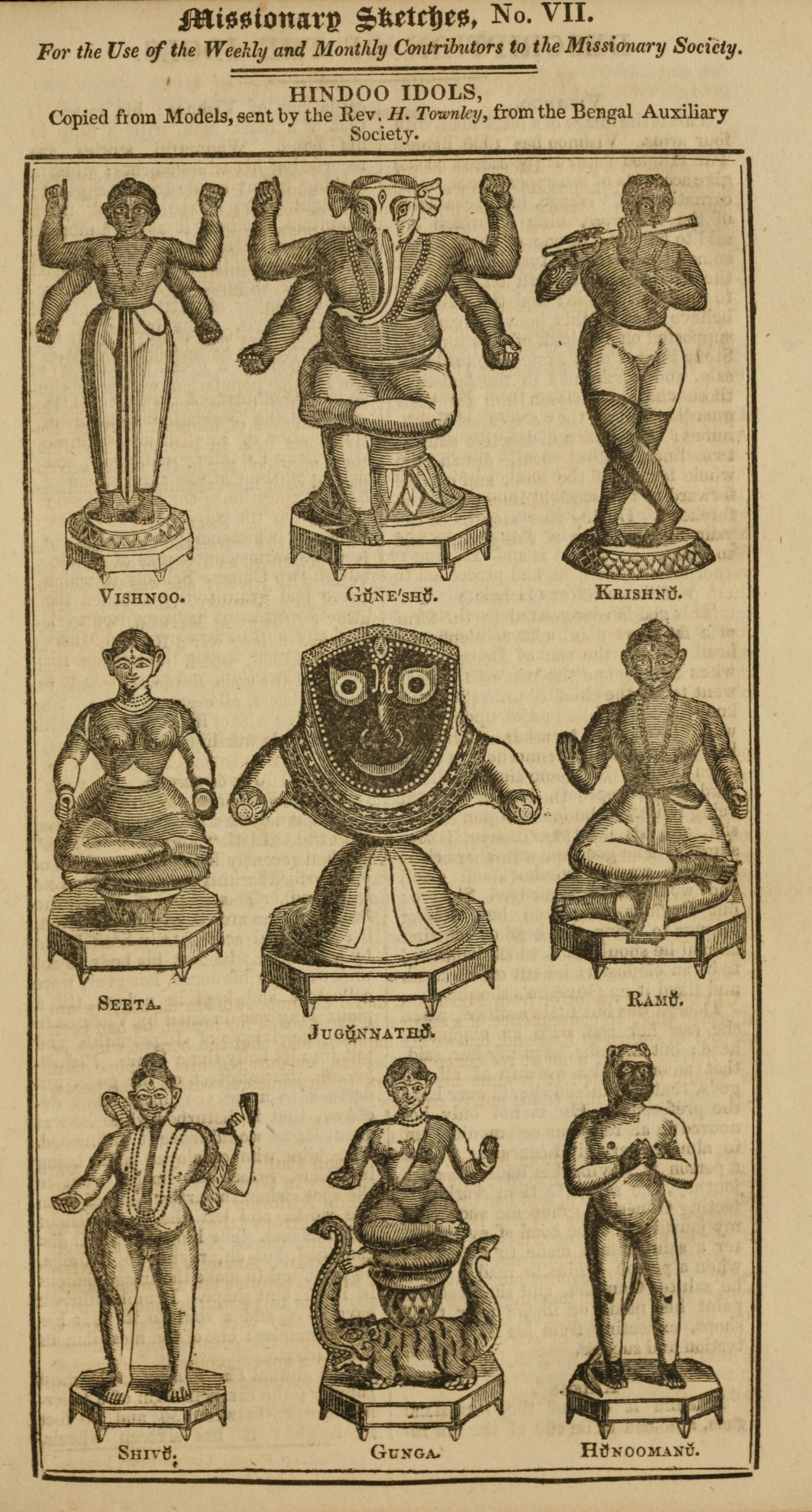

William Ward baptising a Hindoo in the Ganges at Serampore

1821 stipple engraving on paper by Henry Meyer, based on painting by John Jackson. Scottish National Portrait Gallery (CC BY NC): EPL 98.1.

The first volume of Ward’s Account of the Writings, Religion, and Manners of the Hindoos including Translations from their Principal Works was printed at the Mission Press in Serampore in 1806, with the fourth volume completed in 1811, just before a fire destroyed the print works (Ward 1811). A second edition, “carefully abridged and greatly improved”, was printed between 1815 and 1818 under the title A View of the History, Literature, and Religion of the Hindoos, with a third edition printed in Britain by the Baptist Missionary Society between 1817 and 1820.

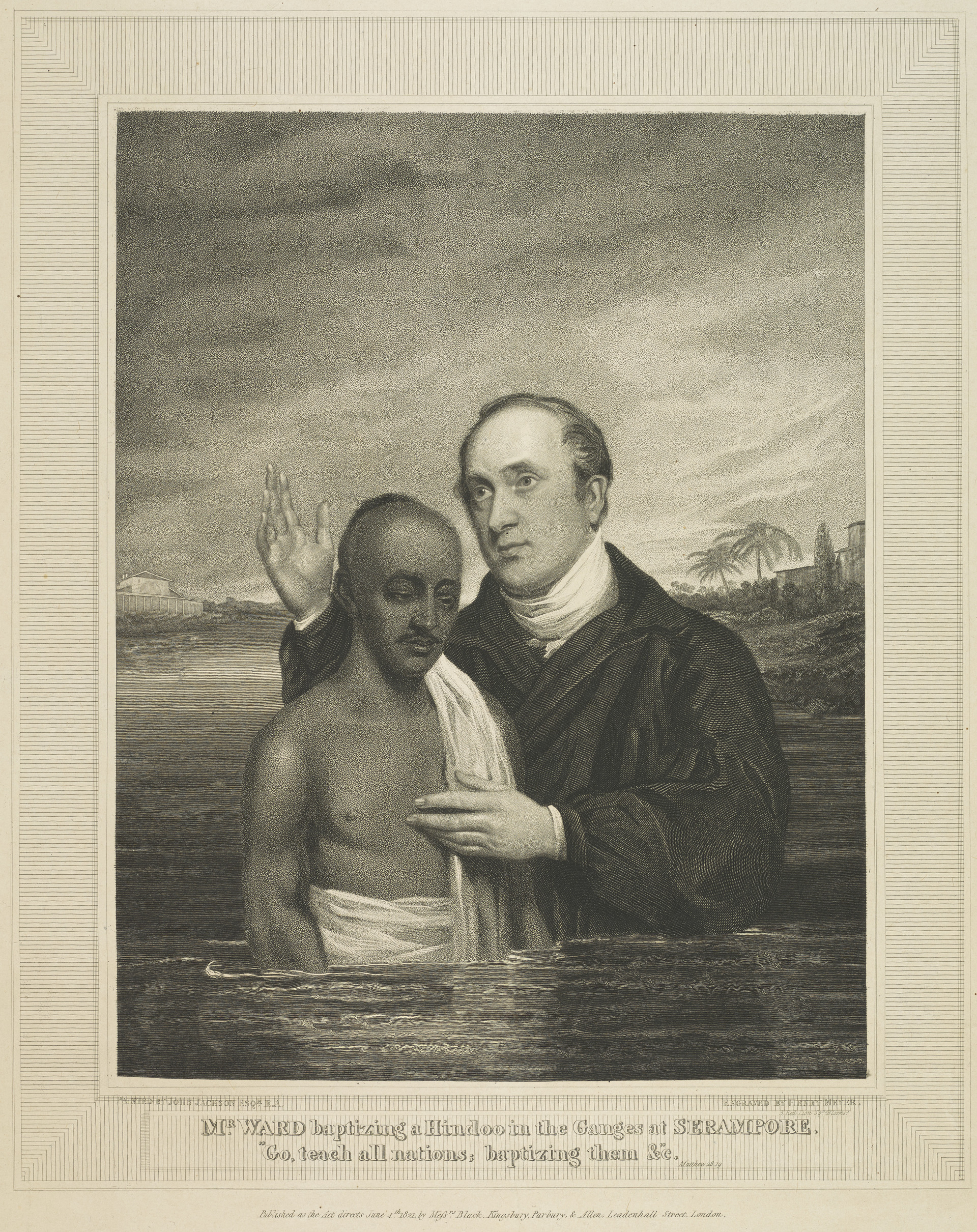

A compendium of Indian religious texts printed in English, alongside descriptions of Hindu practice, Ward provided British evangelicals with an accessible guide to ‘the religion of the Hindoos‘. Even before the arrival in London of Townley’s ‘models’, Ward’s text had been used to compile a description that accompanied an image of Ganesh that was printed in the Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle in March 1818.

It was noted that many Hindus kept a small metal image of the god in their houses for daily worship. The Evangelical Magazine, however, was not content to adopt a position of straightforward condescension in relation to this ‘idolatry’, noting that:

The superstitious regard paid by these blind idolaters to a senseless image, may put to shame many who are better informed, and who call themselves Christians, but who live practically “without God in the world;” who never acknowledge the Creator and Preserver; and who daily go out and return home, amidst a thousand dangers, without seeking his guidance or protection.9

The London Missionary Society sent their first missionary to India in 1798. Arriving five years after William Carey, also without an official licence, Nathaniel Forsyth preached in and around Calcutta with the tacit support of Company officials. With minimal financial assistance from the Society in London, he found Calcutta expensive and lived for a time on a boat, until appointed minister of the Dutch church at Chinsurah (Hugli-Chuchura) in West Bengal.10

Representation of the Indian Idol, Ganesa

Published in Evangelical Magazine, volume 26, March 1818, p. 125. Hathi Trust (Public Domain, Google-digitized): https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.ah6lsg&view=1up&seq=139

Only in 1804 were further missionaries sent to India by the LMS, but they went to the south. In the early decades of the nineteenth century, the major Indian campaigns undertaken by the Society seem to have been largely conducted through a war of words in London.

In July 1806 an uprising at Vellore Fort in Tamil Nadu, South India, following the implementation of new uniform regulations involving the trimming of beards and removal of caste marks, was connected to the circulation of rumours about forced conversion to Christianity. Evangelicals sought to blame the family of Tipu Sultan, imprisoned at the fort, as well as the Madras administration, invoking the weight of British evangelical opinion in an attempt to avert a wholesale recall of missionaries from India.11

Making the case for the opposition was the Rev. Sydney Smith, who, in his essay “Indian Missions” published in The Edinburgh Review of February 1808, quoted the Transactions of the Missionary Society at length to illustrate the strong reactions missionary activity provoked in India. Smith argued that it was perilous to proselytise in a precarious India ‘without incurring the utmost risk of losing our empire’.12 In the essay, which Smith himself later characterised as ‘routing out a nest of consecrated cobblers’13, he famously asked: ‘Why are we to send out little detachments of maniacs to spread over the fine regions of the world the most unjust and contemptible opinion of the gospel?’14

Evangelicals were ultimately successful in defending the admittedly fairly ambiguous status quo, but many of the same arguments resurfaced in the years leading up to the British government’s renewal of the East India Company’s charter in 1813.

Evangelical networks across the British Isles were mobilised in a campaign that led to 908 petitions supporting the promulgation of Christianity in India being submitted to the British parliament, at that time the largest number ever presented.15 In a parliamentary compromise orchestrated by William Wilberforce, all sides were enabled to believe they had achieved some of their aims. A new clause in the charter of the East India Company made it:

the Duty of this country, to promote the interests and happiness of the native inhabitants of the British dominions in India, and that such measures ought to be adopted as may tend to the introduction among them of useful knowledge, and of religious and moral improvement. That in the furtherance of the above objects, sufficient facilities shall be afforded by law, to persons desirous of going to, and remaining in India, for the purpose of accomplishing those benevolent designs.16

One of the major consequences of this clause was the establishment of schools across India, including for girls, supported financially by the East India Company—the Rev. Robert May of the London Missionary Society established thirty schools, educating nearly 3000 children including 700 sons of Brahmins in and around Chinsurah between 1812 and 1816.17 The exterior, interior and plan view of one of these schools was depicted on the cover of Missionary Sketches in October 1820, a year after the cover had featured Townley’s ‘Hindoo Idols’.18

It was in the wake of this campaign and the resulting new clause that Henry Townley had been sent to re-establish the Society’s mission at Calcutta, following the death of Forsyth. The Bengal Auxiliary Missionary Society was established in December 1817 to raise funds locally to support missionary activity.19 Prompted to contribute to the stock of missionary images, Townley, acting on behalf of the Auxiliary Society either purchased or commissioned a set of twenty-two murti (models)—images of Hindu gods.

It is significant these were described as “models”. This may have been an attempt to translate the word murti, which carries a sense that such figures take the material form of a god, without being gods in themselves, but it more likely suggests that they were acquired from the craftspeople who made them, rather than from temples or homes, where they had already been the focus for puja or bhakti (religious devotion). Unlike Pomare’s Family Idols, these were not given up by converts to Christianity, but they remained useful in illustrating the religious practices of India for missionary supporters across the world.

The fact that eight of the murti were arranged on the cover of Missionary Sketches around the black-faced figure of Jugunnathu is significant, reflecting this figure’s centrality to early nineteenth century British imaginations of Indian religion. A note in parentheses in the accompanying written account points out that the name of this God is ‘usually written Juggernaut’, explaining that this name is a title for a deified hero meaning “Lord of the World”.20

The form of the image, with no legs and only stumps for arms but a very large head and eyes was explained: having been commissioned to house the bones of Krishna, its maker was interrupted at work, leaving the image unfinished. Brahma, himself, however, was said to have given the murti its eyes and a soul.

The focus of the printed description in Missionary Sketches then shifts from the image itself to the temple to Jagganath in Orissa and its annual Car Festival. As part of this, the crowd drew a tapering tower containing the image of Jagganath, between 50 to 60 feet high and with sixteen wheels. The description ends by noting:

Unnumbered multitudes of pilgrims, from all parts of India, attend this festival, among whom a great mortality frequently prevails; and hundreds, perhaps thousands of persons, diseased or distressed, have cast themselves under the wheels of this ponderous car, and have been crushed to death.21

The subjugation of Orissa during the Second Anglo-Maratha War of 1803, pursued by Wellesley, placed the temple of Jagannath at Puri, a major site of regional pilgrimage, under the control of the East India Company. The appointment by the Company of a tax collector and committee to manage temple affairs upset evangelicals, who argued that this amounted to state-sponsored idolatry.

The person most responsible for advancing this concern was Claudius Buchanan, an evangelical Scottish Anglican minister appointed to an East India Company chaplaincy in Bengal in 1796, who became vice-provost of Fort William College in 1800, where he worked closely with William Carey.

Representations of One of the Native Schools at Chinsurah In the East Indies

Missionary Sketches, No. XI, October 1820. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n40/mode/1up

HINDOO IDOLS, Copied from Models, sent by the Rev. H. Townley, from the Bengal Auxiliary society

Missionary Sketches, No. VII, October 1819. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n24/mode/1up

In 1811 Buchanan published Christian Researches in Asia22 and in December of that year, the Evangelical Magazine syndicated his description of the festival of Juggernaut in order to ‘kindle the zeal of European Christians in the support and extension of Missionary efforts’ by becoming ‘more intimately acquainted with the horrors of Heathenism’:

I have returned home from witnessing a scene which I shall never forget. At twelve o’clock of this day, being the great day of the east, the Moloch of Hindoostan was brought out of his temple, amidst the acclamations of hundreds of thousands of his worshippers […]’

The idol is a block of wood, having a frightful visage, painted black, with a distended mouth of a bloody colour […] An aged minister of the idol then stood up; and, with a long rod in his hand, which he moved with indecent action, completed the variety of this disgusting exhibition. I felt a consciousness of doing wrong in witnessing it […] The characteristics of Moloch’s worship are obscenity and blood. We have seen the former. Now comes the blood.

After the tower had proceeded some way, a pilgrim announced that he was ready to offer himself a sacrifice to the idol. He laid himself down in the road before the tower, as it was moving along, lying on his face, with arms stretched forwards. The multitude passed round him, leaving the space clear, and he was crushed to death by the wheels of the tower. A shout of joy was raised to the god. He is said to smile when the libation of the blood is made. The people threw cowries, or small money, on the body of the victim, in approbation of the deed. He was left to view a considerable time, and was then carried by the hurries to the Golgotha, where I have just been viewing his remains. How much I wished that the Proprietors of India Stock could have attended the wheels of Juggernaut, and seen this peculiar source of their revenue!23

Buchanan’s reference to Moloch connected Jagannath to the Old Testament book of Leviticus but also to Milton’s Paradise Lost, making it clear he regarded the procession at Puri as a form of demonic idolatry, endorsed and managed by a British commercial company. The image of the immense and unstoppable car of Juggernaut, crushing pilgrims beneath its wheels was so potent that it captured early nineteenth century evangelical opinion, finding an enduring place in the English language.24

In the years that followed, the front cover of Missionary Sketches featured further Indian gods, with commentary supplied by Ward. In July 1820, an image of “Kalee, the black goddess of India” included a description of the animal sacrifices Ward witnessed at a festival in Calcutta:

Never did I see men so eagerly enter into the shedding of blood; the place literally swam with blood. The bleating of the animals, the numbers slain and the ferocity of the people employed actually made me unwell; and I returned about midnight, filled with horror and indignation.25

Kalee, the Black Goddess of India

Missionary Sketches, No. X, July 1820. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n36/mode/1up

In January 1821, the cover featured a representation of “Doorga, a principal goddess of the Hindoos” based on a drawing made and purchased at Chinsurah along with a number of others, distinctive in that:

all the lines by which the figures are delineated are composed of the name of the idol, in the Bengalee character, many thousand times repeated. The ornaments (here omitted) which are very profuse and not inelegant, are formed in the same manner.26

The text described Durga and the features of ceremonies at which she was worshipped, noting a ceremony Ward witnessed at Calcutta in 1806, when:

The whole scene produced on my mind sensations of greatest horror. The dress of the singers – their indecent gestures – the abominable nature of the songs – the horrid din of their miserable drum – the lateness of the hour – the darkness of the place – with the reflection that I was standing in an idol temple, and that this immense multitude of rational and immortal creatures, capable of such superior enjoyments, were, in the very set of worship, perpetrating a crime of high treason against the God of heaven, while they themselves believed they were performing an act of merit.27

Rumours of human sacrifices to Durga were reported, and a footnote enumerated the far larger number of annual deaths in ways that were, according to Ward, sanctioned by the ‘shasters (religious books of the Hindoos)’, which he had calculated:

| Widows burnt alive on the funeral pile | 5000 |

| Pilgrims perishing on the roads and at sacred places | 4000 |

| Persons drowning themselves in the Ganges, or buried or burnt alive | 500 |

| Children immolated, including the rajpoots | 500 |

| Sick persons, whose death is hastened on the banks of the Ganges | 500 |

| 10,500 |

Although not given a number, the body of the text listed another cause of death: ‘by the wheels of the idol Juggernaut’.

Front View of Union Chapel, Calcutta

Missionary Sketches, No. XIX, October 1822. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n72/mode/1up

Representation of Doorgá, A principal Goddess of the Hindoos

Missionary Sketches, No. XII, January 1821. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n44/mode/1up

In April 1822, the cover of Missionary Sketches once again featured an image of Juggernaut, as well as diagrammatic representations of Boloram and Sabattra, his siblings.

The text included a mythical history of the creation of the three murti, abridged from an account drawn up by a Brahmin from Orissa.

The commentary that followed listed a number of features of the narrative, each provided with biblical references, suggestive of Christian parallels that might make the bible—referred to as the “True Veda”—appealing to Hindus.28

Fabulous History of the Temple of Juggernaut, in the Province of Orissa, in the East Indies

Missionary Sketches, No. XVII, April 1822. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n64/mode/1up

The following issue, printed in July 1822, included an image of the procession of Juggernaut, with the textual description taken from Buchannan’s account, eleven years after it had appeared in the Missionary Chronicle—to lay before readers ‘the horrible enormities and abominable idolatries attending the Festival of the Car‘.29

This was juxtaposed with another description by Buchanan of baptism and preaching at Serampore, alongside texts quoted from William Carey and William Ward. Readers were told:

‘Surely no reader of this sketch would hesitate to exert himself, or to subscribe a portion of his property, to put a stop only to the evils connected with the IDOL JUGGERNAUT.’30

Car of the Idol Juggernaut

Missionary Sketches, No. XVIII, July 1822. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n68/mode/1up

Just as Townley’s models were followed on the cover of Missionary Sketches by an image of a Chapel and school at Madras in January 1820, the succeeding issue, printed in October 1822, depicted Union Chapel in Calcutta, opened in April 1821. A centre for missionary activity, it was also intended to make evangelical Christianity available to the many dissolute Europeans living what evangelicals regarded as immoral lives in the capital of British India.31

Readers were provided with a history of the city, including an account of English prisoners dying crowded into the Black Hole Prison in 1756. This was followed by an account of the Serampore translations by the Baptist Missionaries, the work of Forsyth, as well as the arrival of Townley and more recent missionaries in the city.

The London Missionary Society’s grant of 1000 Rupees a year to support the School Society was noted, with the implication that schools and chapels would rapidly replace temples of idol worship across India.

Front View of Union Chapel, Calcutta

Missionary Sketches, No. XIX, October 1822. Internet Archive (Public Domain): https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n72/mode/1up

While the missionary critique of India and its religious institutions was frequently harsh and intemperate, it is striking that it seems to have induced a response from Indian intellectuals.

Ram Ram Basu, who worked with Carey from the 1790s onwards and never converted to Christianity, nevertheless argued for the reform of Hinduism based on the Vedas. He even wrote a Bengali text about Jesus Christ, Christabibaranamrta, in 1803.

In 1817, Mrityunjaya Vidyalankar, an orthodox Brahmin depicted working alongside William Carey on translations at Fort William College compiled a legal report suggesting that the practice of sati (widow burning) was not sanctioned by any Indian holy texts.32

Most famously, Rammohum Roy, who worked alongside Basu, Vidyalankar and Carey at Fort William College spearheaded a movement to reform Hinduism, the principal targets of which were shared with evangelical missionaries: idolatry, the caste system and sati. Sometimes remembered as the “father of the Bengal Renaissance”, Roy was significantly influenced by his engagement with Christianity, publishing The Precepts of Jesus, the Guide to Peace and Happiness in 1820, setting out ethical teachings drawn from the gospels.33

Criticised by some Baptist missionaries for extracting the teaching of Jesus from their framing within a narrative of salvation by grace, premised on Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, Roy continued working on a revised translation of the New Testament with the Baptist Missionary William Adam, only for Adam to leave the Baptists to establish a Unitarian Society in Calcutta with Roy.34

The Rev. W. Carey, D.D. and his Brahmin Pundit (Mrityunjaya Vidyalankar)

1832 line engraving by Joseph John Jenkins after painting by Robert Home (now at Regent’s Park College, University of Oxford). National Portrait Gallery (CC BY NC ND): NPG D2180.

The Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, printed in 1826,35 begins its East Indies section with Case H, containing twenty-one named and numbered ‘Indian idols’. The nine murti depicted in October 1819 are all listed, in many cases alongside descriptions taken directly from the text of Missionary Sketches. In addition to these nine, the following were included in the same list, albeit without the same degree of further description:

| CHOITUNYU, THE WISE | SHIVU LINGU |

| UBHUYA | RADHA |

| LU RUHMUNU | VISWAKARMA |

| NUNDEE | BULURAMU |

| KARTIKEYU | BRUMHA |

| JUGUDDHATREE | LUKSHMEE |

The original note in the Missionary Chronicle of September 1819 referred to ‘twenty-two models of Hindoo deities’. In the seven years between their arrival and the publication of the catalogue, one seems to have been lost or broken.

Case of Indian Idols

Although they appear in nineteenth century images, such as that depicting the case ‘Indian Idols’ at the Missionary Museum, published in 1860, I haven’t been able to locate any of the original twenty-two models, two centuries after they arrived in London.

The closest I have come is a somewhat damaged painted clay figure of Jagganath held by the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (1910.62.84). Made from clay rather than wood, it has a different, less waisted, shape to the image located at the centre of the cover of Missionary Sketches in October 1819.

It therefore seems more likelyto be one of the numerous other representations of Jagganath associated with the London Missionary Society, including some that found their way into a case chiefly featuring images of the Buddha in 1860.

The Pitt Rivers Museum Jagganath appears to best match a black and white photograph, published in 1899 that includes a miniature model of Jagganath’s car.

A Model of the Famous Juggernaut Car

Juggernaut—’the Moloch of Hindoostan’— clearly continued to haunt both missionary imagery and missionary imaginations until the very end of the nineteenth century.

Notes

1 ‘India’, Missionary Chronicle for September 1819, p. 385, https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=Y_gDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA385#v=onepage&q&f=false [retrieved 5.07.22].

2 ‘HINDOO IDOLS’, Missionary Sketches, No. VII, October 1819, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n24/mode/1up [retrieved 5.07.22].

3 ‘HINDOO IDOLS’, Missionary Sketches, No. VII, October 1819, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n25/mode/1up [retrieved 5.07.22].

4Carson, Penelope. 2012. The East India Company and religion, 1698—1858. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, p.53.

5Carson, Penelope. 2012. The East India Company and religion, 1698—1858. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, p.56-7.

6 Carlyle, E. I., revised by Brian Stanley. 2004. Ward, William (1769–1823), missionary in India and journalist. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-28710 [retrieved 05.07.22].

7 Murshid, Ghulam. 2021. Ramram Basu. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh, https://en.banglapedia.org/index.php?title=Ramram_Basu [retrieved 15.07.22].

8 Carson, Penelope. 2012. The East India Company and religion, 1698—1858. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, p.59.

9 1818. Religious Intelligence. Representation of the Indian Idol Ganesa. The Evangelical Magazine and Missionary Chronicle, March 1818, p.125: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7PE6AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle%20december%201818&pg=PA125#v=onepage&q&f=false [retrieved 5.07.22].

10 Lovett, Richard. 1899. The history of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895. 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press, vol. 2: 11-15.

11 Carson, Penelope. 2012. The East India Company and religion, 1698—1858. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, p.71.

12 Smith, Sydney. 1808. Indian Missions. The Edinburgh Review, vol.12, p.173, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hw3mqu&view=1up&seq=185&skin=2021 [retrieved 15.07.22].

13 Smith, Sydney. 1809. Styles on Methodists and Missions. The Edinburgh Review, April 1809, p.40, https://archive.org/details/sim_edinburgh-review-critical-journal_1809-04_14_27/page/40/mode/1up?q=methodism [retrieved 5.07.22].

14 Smith, Sydney. 1808. Indian Missions. The Edinburgh Review, vol.12, p.179: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.hw3mqu&view=1up&seq=191&skin=2021 [retrieved 5.07.22].

15 Carson, Penelope. 2012. The East India Company and religion, 1698—1858. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 139.

16 Carson, Penelope. 2012. The East India Company and religion, 1698—1858. Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, Appendix 4.

17 Lovett, Richard. 1899. The history of the London Missionary Society 1795-1895. 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press, vol. 2: 16.

18 Representations of One of the Native schools at Chinsurah in the East Indies. Missionary Sketches, No. XI, October 1820: https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n40/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

19 Lushington, Charles. 1824. The History, Design, and Present State of the Religious, Benevolent and Charitable Institutions, Founded by the British in Calcutta and Its Vicinity, p. 78, https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=MvgFbfjoUx8C&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&vq=missionary&dq=charles%20lushington%201824%20religious%20benevolent%20and%20charitable&pg=RA2-PA78#v=onepage&q&f=false [retrieved 15.07.22].

.20 Missionary Sketches Vi p.2 ‘HINDOO IDOLS’, Missionary Sketches, No. VII, October 1819, p.2 https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n25/mode/2up [retrieved 5.07.22].

21 Hindoo Idols. 1819. Missionary Sketches No. VII, October 1819: https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n26/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

22 Buchanan, Claudius. 1812. Christian Researches in Asia: with Notices of the Translation of the scriptures into the Oriental Languages, https://archive.org/details/christianresearc00buchrich/page/n6/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

23 India. 1811. Evangelical Magazine, December 1811, p. 461-2, https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=_-86AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA461#v=onepage&q&f=false [retrieved 15.07.22].

24 Altman, Michael J. 2017 The origins of the juggernaut, https://blog.oup.com/2017/08/origins-juggernaut-jagannath/ [retrieved 15.07.22] ; Carens, T.L. 2005. The Juggernaut Roles in England: The Idol of Patriarchal Authority in Jane Eyre and The Egoist. Outlandish English Subjects in the Victorian Domestic Novel, pp. 48-81. Palgrave Macmillan, London, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230501614_3 [retrieved 15.07.22].

25 Kalee, the Black Goddess of India. 1820. Missionary Sketches No. X, July 1820, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n37/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

26 Representation of Doorgá. 1821. Missionary Sketches No. XIII, January 1821, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n44/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

27 Representation of Doorgá. 1821. Missionary Sketches No. XIII, January 1821, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n46/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

28 Fabulous History of the Temple of Juggernaut. 1822. Missionary Sketches, No. XVII, April 1822: https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n64/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

29 Car of the Idol Juggernaut. 1822. Missionary Sketches, No. XVIII, July 1822, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n68/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

30 Car of the Idol Juggernaut. 1822. Missionary Sketches, No. XVIII, July 1822, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n68/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

31 Front View of Union Chapel, Calcutta. 1822. Missionary Sketches, No. XIX, October 1822, https://archive.org/details/missionarysketch00lond/page/n72/mode/1up [retrieved 15.07.22].

32 Ahmed, A.F. Salahuddin. 1965. Social ideas and social change in Bengal 1818-1835, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 112.

33 Richards, Marilyn and Peter Hughes. 2005. Rammohum Roy, Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography, https://uudb.org/articles/rajarammohunroy.html [retrieved 15.07.22].

34 Together with Roy and Dwarkanath Tagore, Adam founded the Calcutta Unitarian Committee in 1821. In 1828, Roy left the Unitarians to establish Brahmo Samaj, a Hindu version of Unitarianism, based on the Vedas. In 1829 he journeyed to England to lobby for a law to be passed by the British parliament against Sati or widow burning. Roy became a supporter of the 1832 Reform Bill, hoping that Britain might succeed in ‘banishing corruption and selfish interests from public proceedings’ but sadly became ill and died in Bristol where he was buried in 1833.

351826. Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, Austin Friar’s, including specimens in natural history… idols … dresses, etc. London. British Library General Reference Collection 4766.e.19(2.)

0 Comments