Dithakong, 26 June 1823

Beaded apron

Made of iron beads and leather

Rumours of a ‘Goth-like army’ of fearsome ‘Mantatees’ ran through the Tswana towns of South Africa’s interior for months. Tales told of people from the southeast with long hair and dark skins wielding sickle-like weapons, terrifying many who heard them. At first Robert Moffat, a young Scottish missionary, dismissed these tales as ‘mere fabrications’, but over time evidence accumulated that the so-called ‘Mantatees’ were rather more than figments of the imagination.1

Moffat finally came face-to-face with a large group of these semi-mythical people on 25 June 1823, gathered outside the town of Old Lattakoo (Dithakong), in what is now South Africa’s Northern Cape. He spoke with an elderly man and his son who were part of the group, resting in the shade of a rock. They claimed to be dying of hunger and begged for meat. When the larger group became aware of the missionary, and perhaps more significantly the twelve armed Griqua men on horseback who accompanied him, they surrounded their herd of cattle for protection. Griqua scouts approached the group, but were greeted with a yell, followed by a hail of weapons.2

Reinforced by a larger commando from Griqua Town (Klaarwater) the following day, another approach at sunrise met with the same response. At this point Andries Waterboer, the Kaptijn or leader at Griqua Town, began to shoot. Counter-attacks were made, but Moffat recorded in his journal that the enemy were reluctant to be parted from their cattle. Women mixed with men in the defence of the herds, with Moffat complaining that this made it impossible to avoid shooting them.3

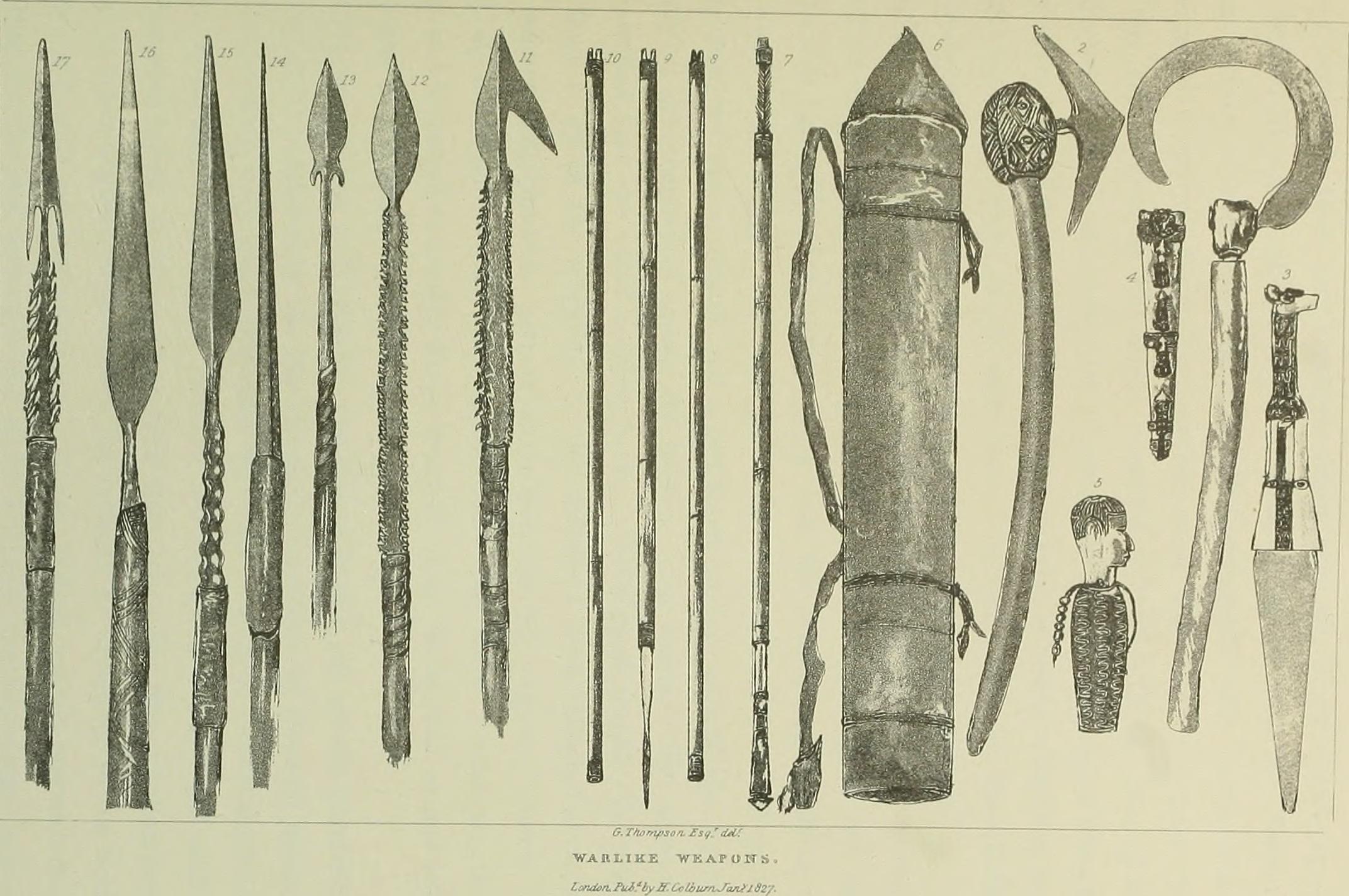

After two and a half hours of battle with a mounted Griqua commando of around 100 supported by Bathlaping warriors firing poisoned arrows, ‘the Mantatees’, on foot and armed with only spears, clubs and axes, attempted to retreat. They made their way into the town which they set alight, perhaps in the hope of creating a distraction. The Griqua, however, pursued the retreating group for eight miles, capturing over 1000 head of cattle.

Moffat recorded that between 400 and 500 ‘Mantatees’ were killed during seven hours of fighting, with only one Tswana combatant killed ‘perhaps from too much boldness in plunder’.4 The disparity in casualties makes it clear how decisive an advantage firearms and horses gave to the Griqua, compared with other groups operating in the African interior.

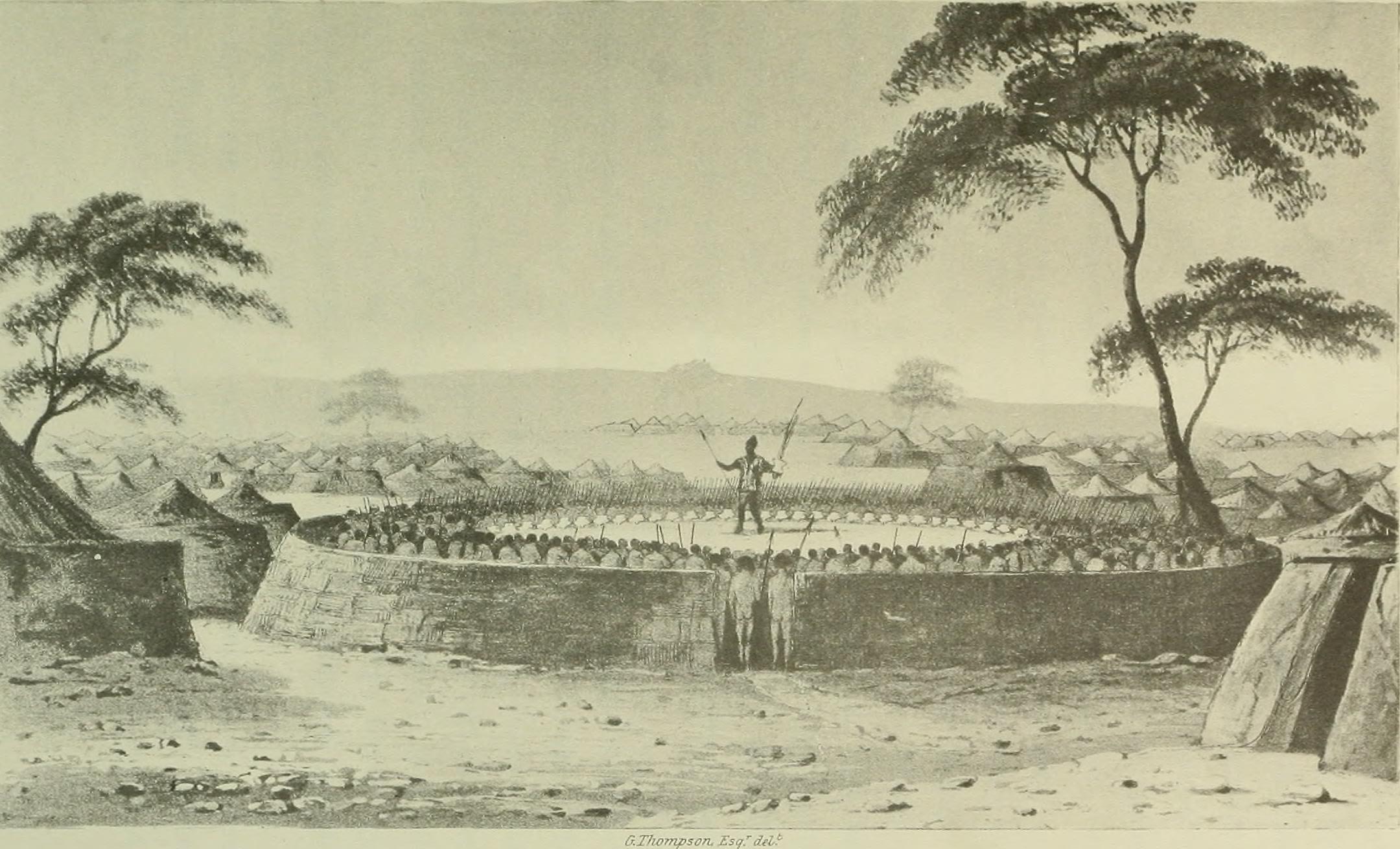

The Town of Leetakoo (Dithakong)

Image based on 1801 sketch by Samuel Daniell, 1804

Moffat’s eyewitness account of what has become known as ‘the Battle of Dithakong’, written in his journal but published in abridged form in the Missionary Chronicle soon after, in January 1824, is somewhat ambivalent.5 He attempts to position himself as witness and bystander, but acknowledges that he was responsible for requesting the assistance of the Griqua when told of approaching ‘Mantatees’, as well as for supplying them with gunpowder.

Moffat remained with the Griqua commando for his own safety, but was, by his own admission, far from being in command of these rather expert fighters. He claims not to have discharged a single shot ‘as fighting was not my province’, but remained implicated in the violent confrontation that unfolded as he watched.6

Having worried about the shooting of women, he evidently became even more upset when Batlhaping warriors joined the fray, killing wounded men, women and children with spears and axes ’like voracious wolves’ with ‘savage ferocity… and severing the head from the body, for the sake of a few paltry rings’. Moffat states that he galloped among them to prevent this slaughter, inducing many women to sit on the ground, bare their breasts and cry ‘we are women’.7

Moffat and the only other European present, John Melvill, a former Government Surveyor at the Cape who had given up a healthy salary to become a government agent at Griqua Town (and would later resign this post to become an LMS missionary), took responsibility for ‘collecting the prisoners’, mostly women and children, after the main body of Griquas ‘galloped forward, anxious to divide the spoil’ – the large herd of captured cattle. At this point, Moffat used italics to remark to his journal: They are heathens still.8

Spoils of battle were not confined to cattle, however, and Moffat noted that the path taken by the retreating enemy was ‘thickly strewed with karosses, victuals, utensils, ornaments, and weapons, which the Bechuanas eagerly gathered up’.9 If Moffat was merely a witness to these scenes of plunder, as his journal implies, how did a number of items apparently taken at the battle, including ‘a Mantatese apron’, find their way to the Missionary Museum in London, and from there to the British Museum where they remain today?

The Battle of Dithakong has come to assume a central place in historical understandings of a period violence, disruption and significant population displacement that unfolded across the interior of southern Africa during the 1820s, known widely as the mfecane or difaqane (depending on which southern Bantu language grouping is preferred). Eyewitness accounts of the battle, provided by both Moffat and Melvill, as well as by George Thompson, a Cape Town merchant involved in run up, though not at the battle itself, makes it one of the best documented conflicts of the period.

After battles later in the century that saw both British troops and Boer voortrekkers on the losing side against Zulu regiments, historians widely connected the conflicts and migrations of the 1820s to the rise of the Zulu kingdom on South Africa’s southeast coast, under its most charismatic King, Shaka. If the history of the world was the biography of great men, then Shaka became a conquering African hero in the form most admired by Thomas Carlyle (1840) – a South African Napoleon.10

In 1966, John Omer-Cooper, based for over a decade at the University of Ibadan in Nigeria where historians were attempting to write African history for its own sake as the country embraced independence, published The Zulu Aftermath, a synthetic work that attempted to Africanise South African history.11 According to one of his contemporaries, Omer-Cooper ‘sought to restore the dignity of Africans as positive actors in their history’.12 Omer-Cooper presented the mfecane as an internally generated African revolution with little to do with European engagements in the region – an independent African history for an independent Africa.

In 1988, Julian Cobbing, writing in South Africa in advance of the end of apartheid published a paper that attempted to upend this way of seeing things. In ’the Mfecane as Alibi’, Cobbing suggested that the notion of the mfecane was a construction of settler history that framed the depopulation of South Africa’s landscape in terms of black-on-black violence in order to justify its occupation by incoming settlers. He pointed out the ways in which it had been propagated ‘with unbelievable rapidity’ through South African universities, schools, the press, television and cinema after 1970 (Shaka Zulu, a major TV series produced by the South AfricanBroadcasting Corporation, first aired in 1986).13

For Cobbing the ‘Afrocentrism’ of the mfecane myth conformed to a pattern – in South Africa’s historical texts whites and blacks were covered in separate chapters with their interactions ‘generally ignored’. As Marxism, in the form of dialectical materialism, came to dominate the theoretical imaginations of many South African scholars during the 1970s and 80s, the idea of ‘a purely internal revolution in ‘Bantu Africa’’’ came to seem increasingly naive – reinforcing the apartheid state’s continued efforts to maintain distinct administrative and conceptual frameworks to account for its variously racialised citizens and subjects.

For Cobbing, the ‘motor of change… was not a self-generated internal revolution with a short time-scale, but rather European penetration, against which black societies threw up a series of complex reactive states, that matured over a much longer period of time’.14 While many of Cobbing’s arguments focused on the details on Zulu history, he deployed the Battle of Dithakong as a pivot ‘on which to hinge a case study’ to test and challenge the assumptions of mfecane theory.15

Cobbing argued that the ‘battle’ was an unprovoked ‘slave (and cattle) raid’ that amounted to a ‘seven-hour massacre’.16 He suggested that a shortage of labour in the Cape, following the abolition of the slave trade in 1807, the exclusion from the Colony of ‘black’ labourers in 1809, and the arrival of British settlers in 1820 made battle captives, particularly women and young boys, extremely valuable. According to Cobbing:

The missionaries tried to depict themselves as succouring the prisoners, and rescuing them from the evil chiefs and starvation (with all those cattle?). There is no doubt, however, that they were fully and consciously engrossed in what they were doing, i.e. collecting slaves, and that the cover of hypocrisy was intended to deflect the certain censure from the government in London and from their seniors in the London Missionary Society if it has leaked out that they were selling people into slavery.17

Re-reading Moffat’s account of the battle thirty-five years after Cobbing published his paper and twenty-five years after I first encountered it on my undergraduate reading list, I remain far from convinced that the missionary was ‘consciously engrossed’ in capturing slaves, however much he may have struggled to account for the events in which he played a part. Moffat was certainly no saint – he regularly came into conflict with others while forcefully pursuing his own agendas – but I remain unconvinced that re-casting him as a villain helps us to better understand the conflict or its wider implications for African history.

While I recognise that an entirely ‘Afrocentric’ framing of the violence of the 1820s is potentially naive, both historically and politically, I can’t help feeling that making Europeans the sole ‘motor of change’ potentially reiterates a narrative of African victimhood, denying a right of self-determination in relation to the way Africans responded to historical events.

In the context of recent battles around the focus and meaning of ‘decolonisation’, Olúfémi Táíwo has pointed to the risk that ‘making European colonisation the pole around which we build our explanatory and narrative structures’ can mean we fail to take African agency seriously.18 There were, after all, many Africans on both sides of the battle that day, but only two Europeans.

As I try to make sense of what happened at Dithakong on 26 June 1823, I return to the surviving textual accounts. Is it possible that Robert Moffat found himself caught in the crossfire of historical forces, and wrote in his journal to figure out what had just happened and what it meant, just as I am also trying to do two centuries later?

I also return to the artefacts that were associated with ‘the Mantatees’ at the Missionary Museum. Are these straightforward trophies – looted from the field of battle as plunder, as Cobbing’s framing of the battle might suggest? Or are they something a little more ambivalent – a form of evidence that anchors the textual accounts, becoming an alternative source to be consulted even while a degree of uncertainty about exactly who ‘the Mantatees’ were, and what they were doing at Dithakong remains.

Ambiguous and ambivalent, their digital images continue to bear witness to an event around which competing narratives continue to swirl. Perhaps in order to better assess the reliability of Robert Moffat’s account, we need to know a little about who he was and what he was doing at Dithakong in the first place.

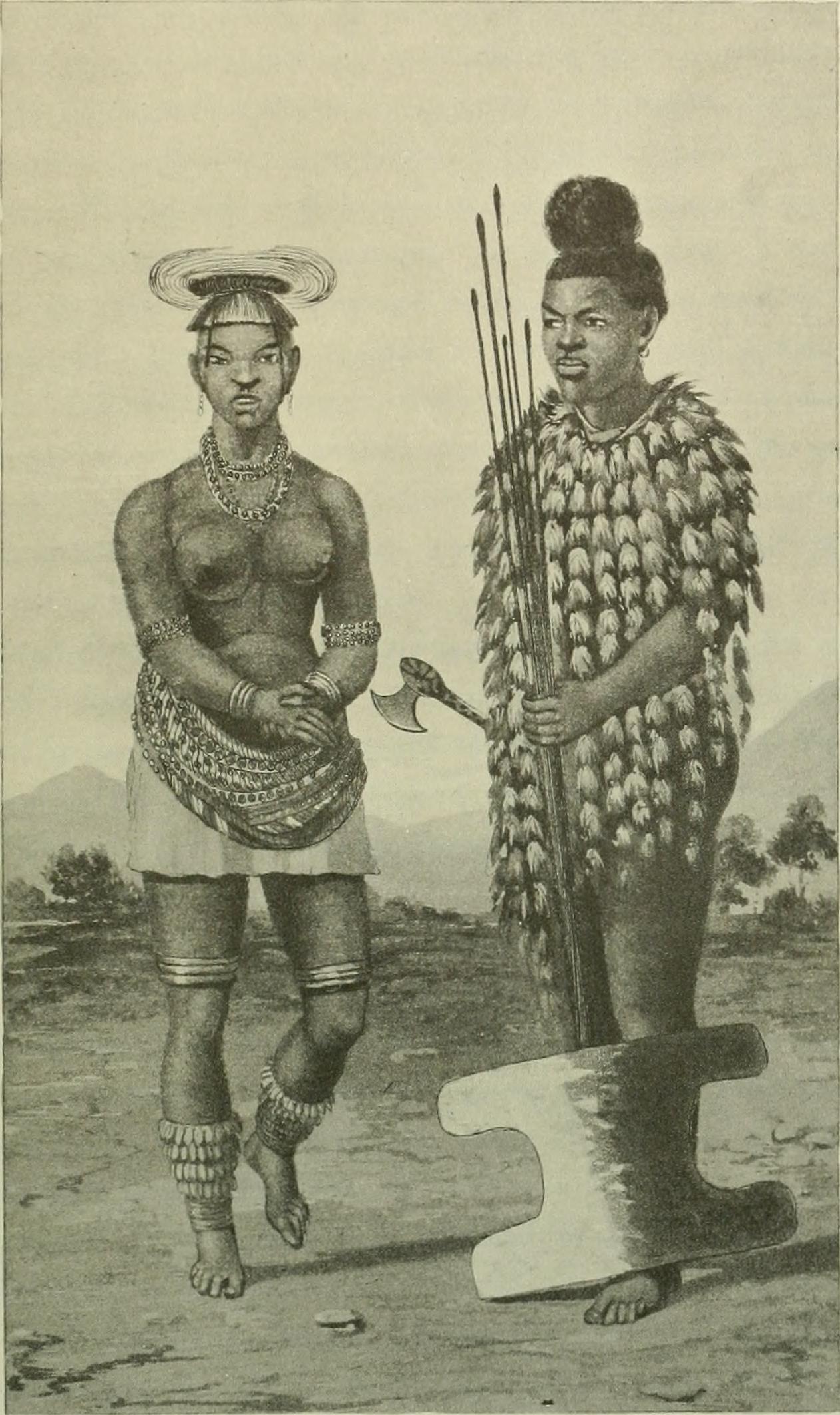

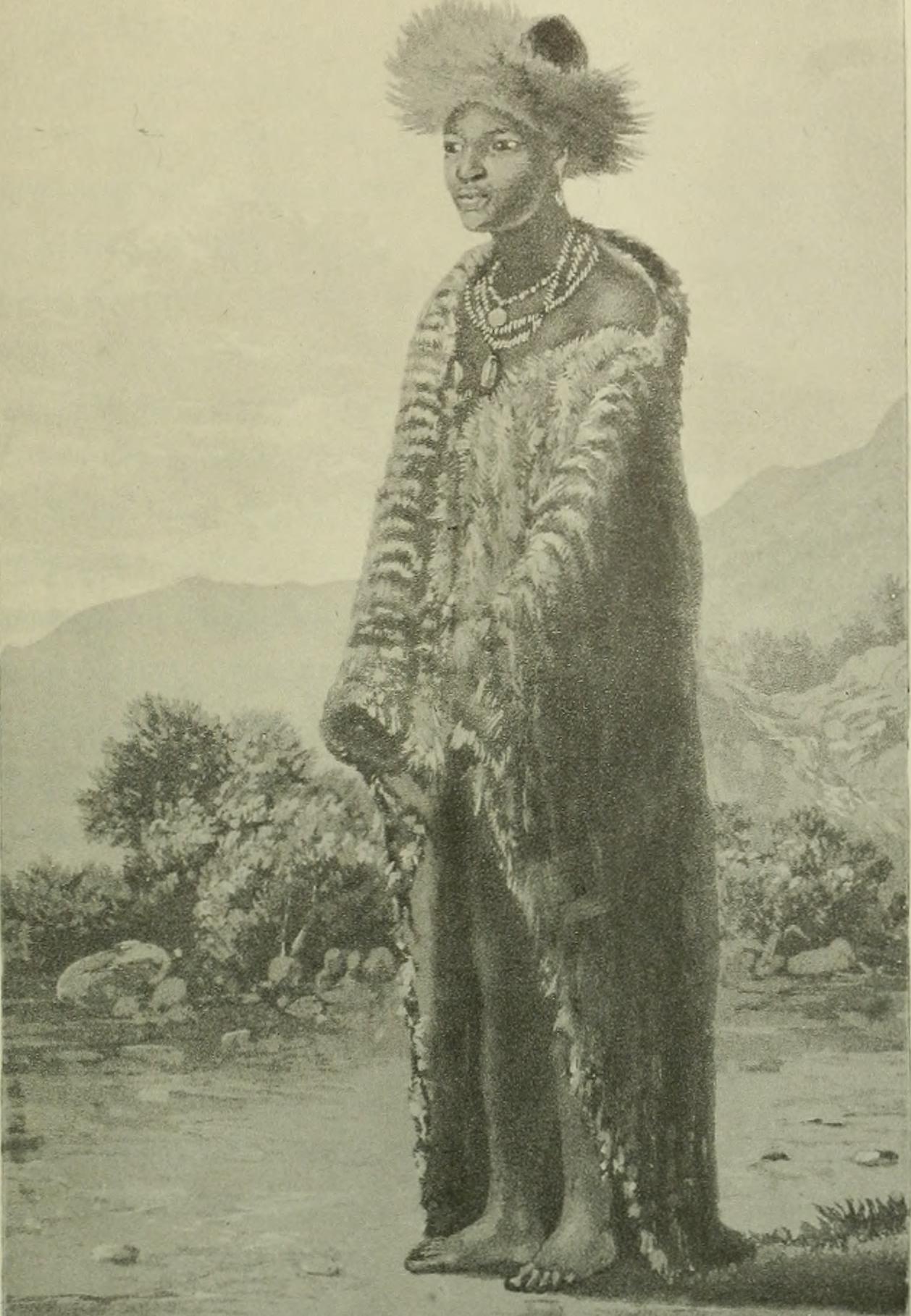

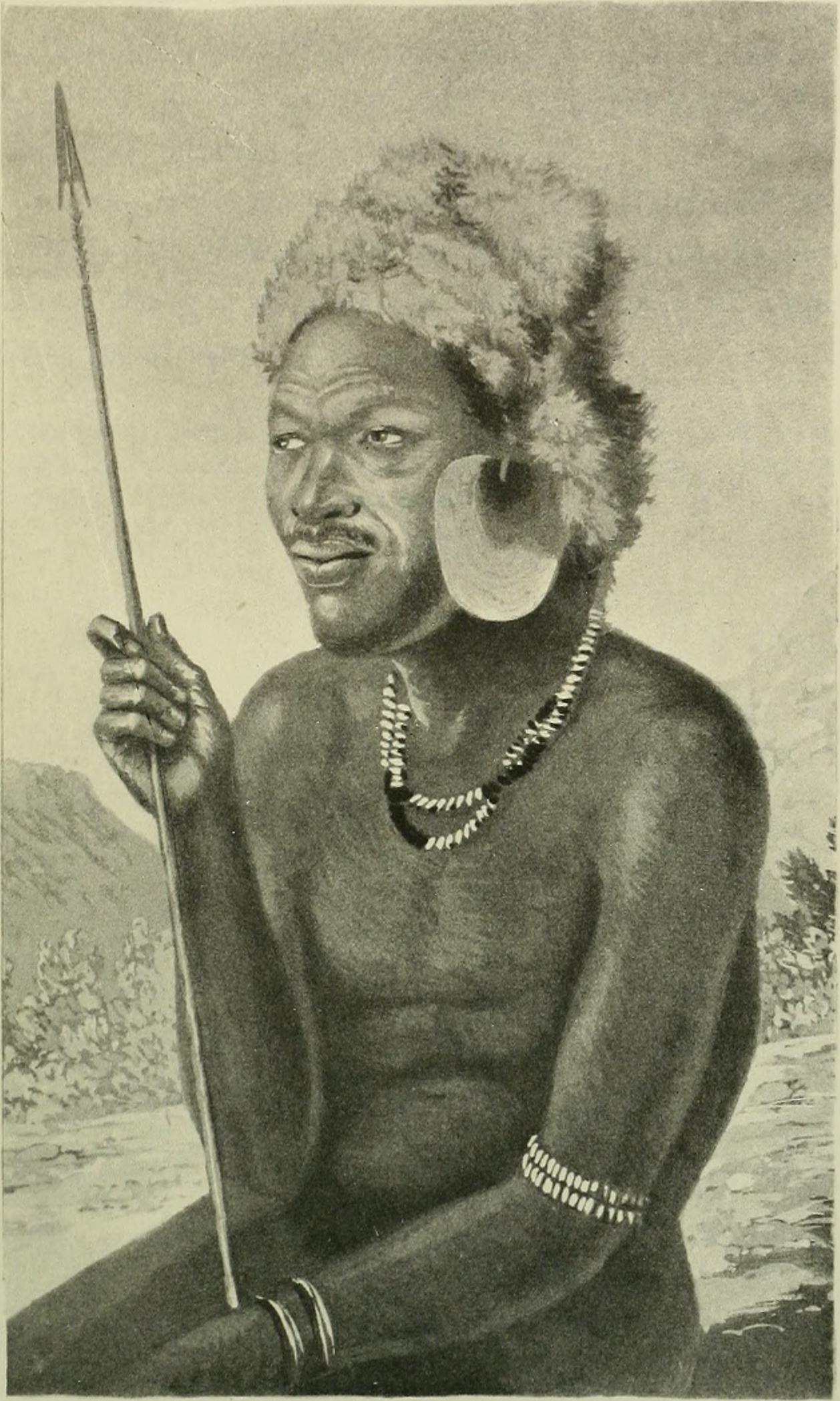

Matclhapee (Batlhaping) Warrior and Woman

Published as Figure 9 in George Thompson’s 1827 Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa.

Warlike Weapons

The distinctinctive ‘Mantatee’ sickle club can be seen on the far right.

Published as Figure 12 in George Thompson’s 1827 Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa.

Detail of sickle like club

British Museum Accession Number

Likhau

Large angular plate of copper, worn across the breast by Mantatee warriors.

From the London Missionary Society Museum

British Museum Accession Number

Born at Ormiston in Scotland in 1795, Moffat spent a period at sea as a cabin boy before being apprenticed to a gardener at the age of fourteen. Working at an estate in Cheshire, he became involved with the Methodist movement, ultimately coming under the influence of William Roby, minister of the Grosvenor Street Congregational Church in Manchester. Roby arranged for Moffat to be employed at a garden nursery in the city in 1816, while he prepared for life as a missionary.

In September 1816, Moffat travelled to the headquarters to of the London Missionary Society, where according to a letter he sent to his parents:

I spent some time in viewing the museum, which contains a great number of curiosities from China, Africa, South Seas and West Indies. It would be foolish for me to give you a description. Suffice it to say that the sight is truly awful, the appearance of the wild beasts is terrific, but I am unable to describe the sensations of my mind when gazing on the objects of pagan worship. Alas! how fallen my fellow-creatures, bowing down to forms enough to frighten a Roman soldier, enough to shake the hardest heart. Oh that I had a thousand lives, and a thousand bodies: all of them should be devoted to no other employment but to preach Christ to these degraded, despised, yet beloved mortals. I had not repented in becoming a missionary, and should I die in the march, and never enter the field of battle, all will be well.19

The recently opened museum clearly served to reinforce, if not inspire, the commitment of aspiring missionaries such as Moffat. At a service on 30 September involving John Campbell, the ‘African traveller’, Moffat was dedicated for missionary service alongside eight others, four for the Pacific (including John Williams) and four others for South Africa. On 18 October, he sailed for South Africa on the Alacrity, arriving at Cape Town in January 1817.20

Permission to leave the colony was refused by the Governor, who was concerned that Griqua Town was becoming a place of refuge for servants and slaves fleeing the colony, so Moffat lodged at a wine farm in Stellenbosch where he learned Dutch until he received permission to go to Namaqualand the following September.

Moffat arrived at the kraal of Jager Afrikaner (literally African Hunter) in late January 1818. A métis group of Khoe descent, much like the Griqua, Afrikaner’s people had a reputation as raiders and rustlers who traded cattle and ivory with the Colony from the lands beyond. Jager was an outlaw with a price on his head, having killed the white farmer by whom the group had originally been employed (and with whom they had engaged in raids).

Three German missionaries, recruited by Johannes Kicherer during his visit to Europe, had begun work with Afrikaner’s people in 1805. One of these, Johannes Seidenfaden, later memorably described as ‘a wolf in sheep’s clothing’, seems to have set about enriching himself from the proceeds of Afrikaner’s ivory trade with the Cape, which provided the guns and powder necessary for hunting and raiding.21

In 1811, Jäger Afrikaner raided Seidenfaden’s mission station at Pella, pillaging his house and taking a barrel of gunpowder and a pair of guns, forcing the missionaries to retreat to Cape Town. Following a visit by John Campbell in 1813, a mission was re-established with Afrikaner in 1815, and in July of that year he was baptised – an event the historian Nigel Penn has regarded as marking the beginning of a a process of closure for the Cape colony’s northern frontier.22

In 1819, Robert Moffat arranged for Afrikaner to travel to Cape Town, where he displayed his credentials as an exemplary convert, in the process being awarded a wagon and the right to enter the colony by the governor.23 While in Cape Town, Moffat met John Campbell and John Philip, fellow Scots who had been sent by the Directors of the LMS to adjudicate in a complicated set of grievances brought by a new generation of missionaries, including Moffat, against the older guard.

Campbell and Philip persuaded Moffat not to abandon his missionary calling, but rather to accompany them as an interpreter on a journey of inspection while he awaited the arrival of his intended bride, whose parents had finally agreed that she could make the journey from Manchester. Having visited Bethelsdorp and other mission stations in the East of the colony, Moffat and Philip returned to Cape Town where they met Mary on her arrival in December 1819 (her own inspiration for missionary work came from hearing John Campbell speaking in Manchester about his first journey to South Africa).24

Robert and Mary were married 19 days later, and it was decided that Moffat should take over the mission at New Lattakoo (Maruping) – James Read, originally stationed at Bethelsdorp with Vanderkemp in 1799, had taken himself there in self-imposed exile after admitting to charges of sexual impropriety.

The Moffats travelled north with John Campbell early in 1820, arriving at Griqua Town late in the evening on 13 March where they found men making square buildings out of stone and women ‘dressed in European fashion’ sewing cotton clothes. While there, a wagon arrived with a party of thirty Batlhaping led by a Griqua missionary, Jan Hendric, who taking ivory to trade at a market arranged at the edge of the Cape Colony at Beaufort West, 500km to the South.25

On 21 March, Campbell and the Moffats set off for Kuruman, and on their journey encountered more people taking skins, assegais, knives, shields to trade for beads at fair. Campbell noticed that compared to his journey four years earlier, wild game had become much scarcer due to the hunting activities of Griqua and their guns.26

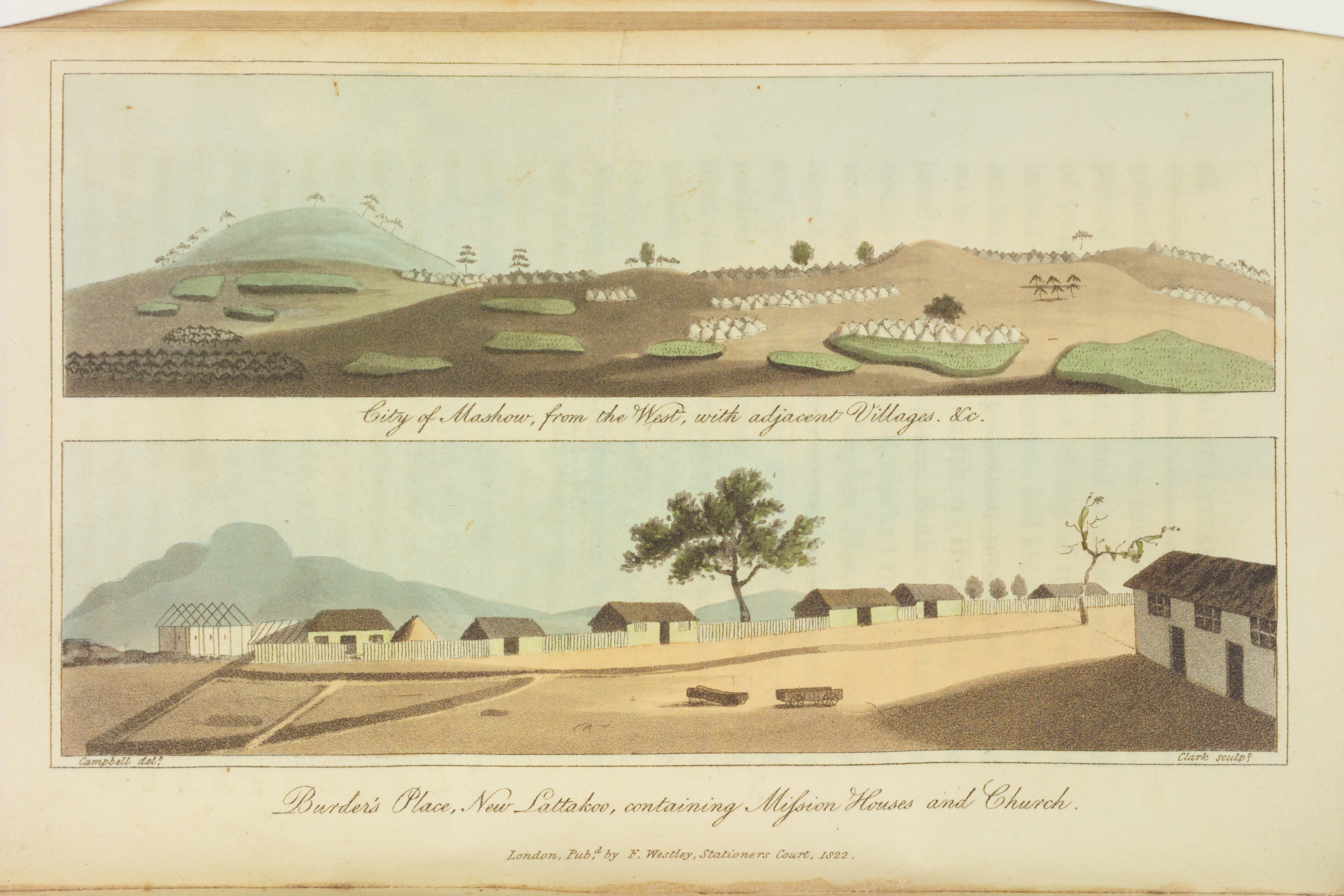

Arriving at the mission, they found a row of missionary houses behind a neat reed fence, with gardens at the back, as well as a church capable of holding four hundred people. They had brought a bell to be hung near the church to replace the horn used previously to summon people to worship.27

They were visited at the home off Robert Hamilton by the King or Kgosi, Mothibi, as well as various other nobles , who were presented with gifts ranging from snuff, beads and buttons to tinder-boxes and kaleidoscopes. Moffat bargained for a two gallon wooden container, made by the neighbouring Bakwena, while some of the visitors amused themselves examining portraits from the Evangelical Magazine displayed on the walls, including one of Campbell himself.

Campbell expressed his satisfaction that under the influence of James Read, Mothibi had ceased the system of commandoes to raid cattle from neighbouring groups, but Mothibi pointed out that without this source of income, he needed guns and gunpowder to hunt wild animals.28

Burder's Place, New Lattakoo (Maruping), containing Mission Houses and Church

Published along with an image of the Barolong city of Mashow (Moshaweng) in John Campbell’s 1822 Travels in South Africa.

Sketched by John Campbell, engraved by John Heaviside Clarke.

When Campbell and Read departed on a journey to the North, visiting Dithakong as well as the substantial city of Kaditshwene – but also meeting Campbell’s old friend Cupido Kakkerlak then serving as a missionary to the Coranna – the Moffats stayed at Maruping to establish relationships at what would become their new station.

In the meantime Jager Afrikaner arrived with a wagon of Moffat’s belongings, including many books. When Campbell returned to the colony with Read, much to the displeasure of the residents of Maruping, the Moffats went for a time to Griqua Town, before joining Hamilton permanently at the mission in May 1821, still in their mid-twenties.29

It was at in the course of attempting a journey of his own to the Tswana towns of the North-East that Moffat met reports that invading Mantatees close at hand had in fact overrun many of these towns, including Kaditshwene. Fearing for the safety of his young family, he returned to Maruping to decide on a course of action. While the Batlhaping prepared for war, Moffat rode to Griqua Town to request assistance.30

On June 13 1823, a pitsho or parliament of armed men, assembled. One old man exhorted the crowd by telling them it was the pitsho of the missionary, and as such they should speak and act not like Batswana but like Makgoas (white people). The Makgoas, meanwhile, buried their possessions so that they could make a quick escape.31

Peetsho (Pitsho) or Great Public Council of the Matclhapees (Batlhaping)

Published as Figure 7 in George Thompson’s 1827 Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa. From an in situ sketch.

Success in repelling the invading ‘Mantatees’ seems to have marked a significant material change for both the Moffat household, by then featuring two very young children, and the mission of which they formed a part. In a letter to Mary’s parents dated 23 July 1823, from Griqua Town less than a month after the battle, Robert Moffat declared that four of the ‘prisoners’ were ‘inmates’ of his family:

Mason or Mahum (Mmahuma), a woman about 25 yeas of age; Moshanee, also a woman, rather older; Fahaange, a boy, about eight years old; and a girl about four (Niywe). Mary has made Mahum, cook, and Moshanee nurse and washerwoman; and the boy, who seems clever, I shall find useful. Considering their former savage state, they do exceedingly well. Moshanee makes a good nurse, and helps to wash very well. This is a great comfort to Mary, as washing is her greatest hardship in this climate. They seem very happy in their new situation, and pleased with their clothes…32

Returning to Maruping in August, Moffat found his garden destroyed but much of his former home in a better state than expected. He subsequently rescued another starving refugee be found being beaten with stones by some boys, taking her to his kitchen where he gave her food and clothing.

The provision of food and clothes allowed Moffat to present the ‘Mantatees’ as the recipients of charity, but their deployment as supplementary household labour – feeding and washing the Moffat family – suggests that the relationship was rather more complicated. Indeed, their exact status seems to have been fairly ambiguous – the fact that Moffat refers to them as ‘prisoners’ and ‘inmates’ seems significant.

Moffat used his newfound influence to argue for the mission’s relocation to a reedy valley eight miles closer to the spring at Kuruman known as Seodin – a seemingly ideal location for someone trained as a gardener. Kgosi Mothibi agreed to grant two miles of the valley adjacent to the island to the missionaries, noting that their presence might provide protection for his cattle from raiding nearby ‘bushmen’.

These arrangements having been made in principle, Moffat set off for Cape Town in October 1823 to seek approval from LMS superintendent John Philip, with a promise to return with the necessary goods for a remuneration – variously described as 40lbs of beads or a small sum of around £5.33

Moffat took with him Kgosi Mothibi’s son and heir, Phetlu, as well as an advisor, Thaišo, who became celebrities at the Cape. They visited the city’s famous castle, its schools as well as the museum, a year before its official establishment. George Thompson, who had met them during preparations for the battle, commissioned their portraits by a recently arrived English artist, Henry Clifford de Meillon. Phetlu and Thaišo seem to have been struck by the ships, but were especially pleased when presented with two guns and some powder by the Governor, who they told ‘had made their hearts white’.34

It was presumably from Cape Town that Moffat forwarded a series of items to the Missionary Museum, had so impressed him just over seven years earlier. These were listed in the Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, printed in 1826 with a description on page 38:

NECK RINGS, used by the Chiefs’ wives of the Mantantese.

The nation is very remote in the interior of South Africa, about 40,000 of whom left their country on a plundering expedition, pillaging all the counties through which they passed, till they reached the city of Lattakoo, in the neighbourhood of which they were repulsed. On this occasion, these rings, with various other articles, were taken. The four rings were worn by one female.

COPPER ORNAMENTS, worn by the same nation.35

In addition, the following items featured as part of a list of material from a shelf on page 42:

29. A COPPER RING, from the Mantantese.

32. A Mantantese NEEDLE.

33. A Mantantese KNIFE.

35. A Mantantese APRON.

A later version of the catalogue, printed around 1860 listed the same apron as:

A Manatee female apron of iron beads. – Presented by Rev. R. Moffat

While it seems likely that this was picked up on the field of battle, it remains possible that it was given to Moffat by one of the women who was taken into his household when they were provided with European clothes. This ambiguity parallels the ambiguous legal status of the women. Were they refugees or captives, enslaved or free?

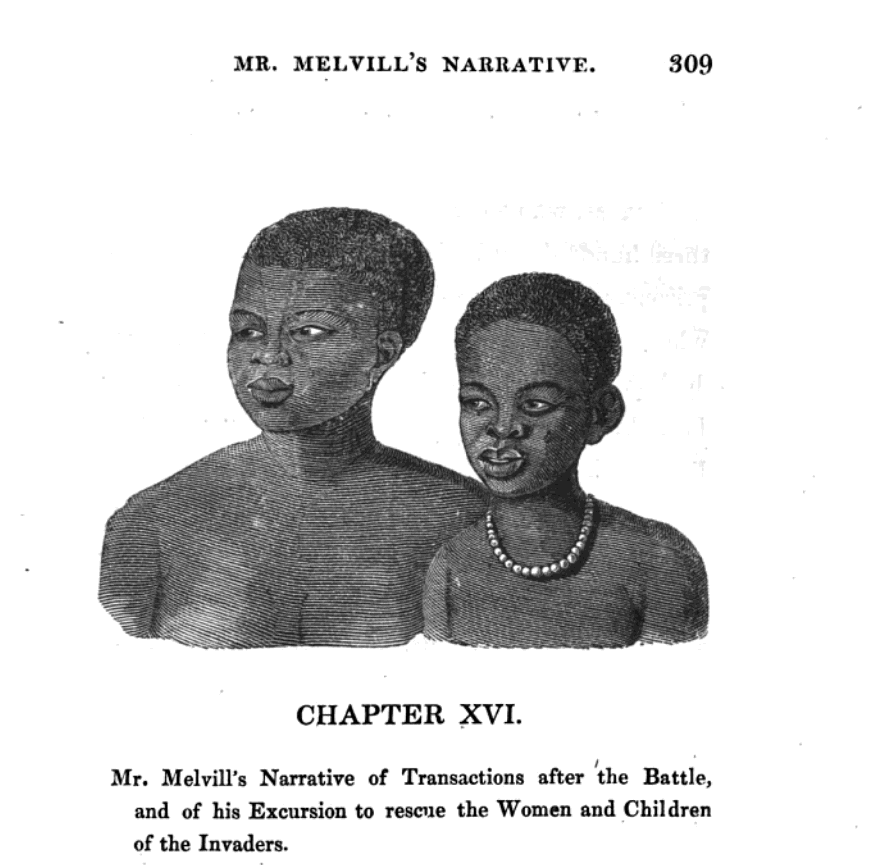

As well as these ‘Mantatee’ artefacts, Moffat seems to have taken five ‘Mantatee’ women and a boy with him to Cape Town. While there are no surviving individual portraits like those of Phetlu and Thaišo, George Thompson’s 1827 account of his Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa does include a vignette of ‘Mantatee Portraits’ at the beginning of Chapter XVI. A footnote on p.320 states that they were rescued by Messrs. Melvill, Hamilton and Moffat:

The female, by name Mahum, has a mild and pleasing countenance, as, indeed, most of the Mantatee females have, indicating nothing of cannibal ferocity. She is now in Cape Town, and has proved herself a very good and faithful servant.

The other figure is that of a boy about nine years of age, named Tahana. He was saved by Mr. Moffat, and having lost all his own relatives, has become affectionately domesticated in the family of his benefactor.

A report in the Missionary Chronicle for November 1824 suggests that their status remained uncertain within the colony, since when travelling through Stellenbosch, the Mantatee women, walking at a small distance from the wagon were arrested by two constables and taken to prison. When missionaries appealed to the Landdrost the following morning, the women were released. However, it does not seem to have been the constables alone who were unclear about the legal status of these women within the colony.

When asked about the captives from the battle at an enquiry on 20 April 1824, Moffat declared that rather than being captives:

the women and children, who were left on the field, abandoned and famished, were offered protection, which many of them accepted, to save their lives; and it was explained to them by Mr. Melville and myself, that they had the option of following in search of their tribe, or of remaining; a few went away, but the greater part remained on the field, and a few came with us; these were taken into the houses of those Griquas who were able to provide for them. It will probably now have been settled on what footing they are to remain with them.

Mr. Melville sent some of them to Graaf Rennet… The Mantatee women, I have understood, were distributed in the colony amongst the Boors, but upon what footing I do not know. The Griquas entrusted to bring them into the colony received 100 rix dollars from the landdrost…

I brought six into the colony. Three were left with Mr. Baird at Beaufort, from my knowledge of the care he would take of them, and two are in the care of Dr. Philip. One I brought down, at the request of Mr. Melville, for his sister; but as she had died I made this woman over to Mr Melville’s father-in-law, who I remember to have exposed his intention of having her booked in; but I admonished him that the woman was free, not understanding what he meant by booking in.

Robert Moffat may not have thought he was engaged in a slave raid, but that clearly doesn’t mean that everyone else, including the ‘Mantatee women’ themselves, regarded things that way. He declared in 1824 that the Botswana ‘have a servile class, but no slaves’, but quite how the captives of battle expected to be treated remains unclear from a distance of two centuries.

In 1823, slavery continued to exist within the Cape Colony although the 1807 abolition of the slave trade had cut off the supply of enslaved people to this largely plantation-based economy. How different in practice, if perhaps not in law, was the status of the young orphaned Tahana when ‘affectionately domesticated in the family of his benefactor’, to that of someone who had been formally enslaved?

Does it make a difference today whether the metal apron was taken from the body of someone who was alive or dead, or indeed whether it was taken by Moffat himself or rather by an African combatant?

Portrait of Peclu (Phetlu), son of King Mateebe (Mothibi)

Published as Figure 6 in George Thompson’s 1827 Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa.

Portrait of Chief Teysho (Thaišo)

Published as Figure 8 in George Thompson’s 1827 Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa.

Portrait of Mahum and Tahana

Published as vignette in George Thompson’s 1827 Travels and Adventures in Southern Africa.

Comments

This is an experiment in writing – that is intended to stretch the idea of the academic monograph.

I am keen to recognise and incorporate the input and expertise of others into the writing process, so adding comments here is one way to do this.

I would welcome any comments or feedback.

Notes

1 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 73; Moffat to James & Mary Dukinfield, Lattakoo, 12 April 1823.

2 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 91; Journal entry 25 June 1823.

3 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 92-3; Journal entry 26 June 1823.

4 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 95; Journal entry 26 June 1823.

5 Missionary Chronicle for January 1824, p. 32: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=n_EDAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA32#v=onepage&q&f=false

6 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 94; Journal entry 26 June 1823.

7 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 94; Journal entry 26 June 1823.

8 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 96; Journal entry 26 June 1823.

9 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 94-5; Journal entry 26 June 1823.

10 Carlyle, T. 1841. On Heroes, Hero-Worship & the Heroic in History.

11 Omer-Cooper, J. 1966. The Zulu Aftermath: A Nineteenth-Century Revolution in Bantu Africa.

12 CHRISTOPHER SAUNDERS (1998) John D. Omer-Cooper, Historian of South Africa (1931–1998), South African Historical Journal, 39:1, 162, DOI: 10.1080/02582479808671336

13 Cobbing, J. (1988). The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo. The Journal of African History, 29(3), 487–519. http://www.jstor.org/stable/182353

14 Cobbing, J. (1988). The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo. The Journal of African History, 29(3), 518.

15 Cobbing, J. (1988). The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo. The Journal of African History, 29(3), 489.

16 Cobbing, J. (1988). The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo. The Journal of African History, 29(3), 492.

17 Cobbing, J. (1988). The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo. The Journal of African History, 29(3), 493.

18 Táíwo, O. 2022. Against Decolonisation. Taking African Agency Seriously.

19 J.S. Moffat, 1885. The Lives of Robert & Mary Moffat, p.26. – https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7gRAAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=The%20Lives%20of%20Robert%20%26%20Mary%20Moffat&pg=PA26#v=onepage&q&f=false

20 J.S. Moffat, 1885. The Lives of Robert & Mary Moffat, p.27. – https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=7gRAAQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=The%20Lives%20of%20Robert%20%26%20Mary%20Moffat&pg=PA27#v=onepage&q&f=false

21 Penn, Nigel 2005. The Forgotten Frontier. Colonist & Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern Frontier in the 18th Century, p.281.

22 Penn, Nigel 2005. The Forgotten Frontier. Colonist & Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern Frontier in the 18th Century, p.284.

23 Penn, Nigel 2005. The Forgotten Frontier. Colonist & Khoisan on the Cape’s Northern Frontier in the 18th Century, p.284-5.

24 J.S. Moffat, 1885. The Lives of Robert & Mary Moffat, p.27.

25 Campbell, J. 1822 Travels in South Africa, undertaken at the request of the London Missionary Society; Being a Narrative of a Second Journey in the Interior of that Country, p.55-56.

26 Campbell, J. 1822 Travels in South Africa, undertaken at the request of the London Missionary Society; Being a Narrative of a Second Journey in the Interior of that Country, p.60.

27 Campbell, J. 1822 Travels in South Africa, undertaken at the request of the London Missionary Society; Being a Narrative of a Second Journey in the Interior of that Country, p.65, 69.

28 Campbell, J. 1822 Travels in South Africa, undertaken at the request of the London Missionary Society; Being a Narrative of a Second Journey in the Interior of that Country, p.107-8, 66, 75.

29 Moffat, R. 1842. Missionary Scenes and Labours in Southern Africa, p. 238.

30 Moffat, R. 1842. Missionary Scenes and Labours in Southern Africa, p. 340-346.

31 Moffat, R. 1842. Missionary Scenes and Labours in Southern Africa, p. 351, 354.

32 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 105; Robert Moffat to James & Mary Smith, Dukingfield, 23 July 1823.

33 Schapera, I. 1951. Apprenticeship at Kuruman, being the journals and letters of Robert and Mary Moffat 1820-1828, p. 113 note 29, 189.

34 Visit of Peclu, the Lattakoo Prince to the Cape. Missionary Chronicle for January 1825, pp. 38-9, https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=2t86AQAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&dq=missionary%20chronicle&pg=PA38#v=onepage&q=museum&f=false

35 Catalogue of the Missionary Museum, 1826, pp. 38-39.

0 Comments